© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1933 to 1939 - Muslim Slaughter in Xinjiang

1933 - 1939

Christians leaving church in Kashgar in happier times.

The church was destroyed in the 1930s persecution.

The vast desert expanses of northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region are home to more than 10 million Muslims belonging to a host of different ethnic minority groups including the Uygur, Kazak, Kirgiz, Uzbek, Tajik, and Hui. Xinjiang is much more historically, culturally, and linguistically akin to nearby Central Asian nations than to China.

The city of Yarkant (known as Shache in Chinese) has a population of around 700,000 people today, 95% of whom are Muslims. Located in western Xinjiang, Yarkant has also been a hotbed of fanatical Islamists for centuries. The first Christian to experience the wrath of Yarkant’s Muslims was Portuguese Catholic priest Benedict de Goës, who reached Yarkant in November 1603 after an exhausting 13-month trek from the Indian city of Agra. Goës was soon hauled before the local religious leaders, who tried to force him to denounce Christianity and embrace Islam. Goës gave a firm and clear rebuttal. The Yarkant leaders

“…could not understand how an intelligent man could profess any religion but their own. Elsewhere Goës was treated less civilly, several times barely escaping with his life from the scimitars of fanatics determined to make him invoke the name of Mohammed.”[1]

On one occasion, Benedict de Goës was affronted by a furious Muslim who burst into the house where he was staying. The man placed

“…his scimitar against his breast, threatened to plunge it in, if he did not instantly render homage to the prophet Mohammed. The courageous missionary calmly looked at him, gently put aside the scimitar, and said, ‘Go, I know not who Mohammed is.’”[2]

One of the greatest mission figures of the 19th century is a name few Christians in the English-speaking world are familiar with. Nils Fredrik Höijer travelled through Russia, the Middle East, and Central Asia in the 1870s and 1880s, preaching the gospel in spite of tremendous opposition and difficulties.[3] Through Höijer’s tremendous courage and persistence the Swedish Missionary Society was founded in 1878. Dozens of pioneer missionaries were sent out over the following decades. Wherever the Swedes went they seemed to encounter more success than other Protestant missionaries working in similar areas. In 1892 they established a work at the strategic city of Kashgar in western Xinjiang, which was then known as Chinese Turkestan. For the first two years the mission had just one worker—Mehmed Shukri, the son of a Muslim mullah from Erzerum, Turkey. Shukri, who changed his name to Aveteranian after his conversion to Christ, proved to be a highly effective evangelist in Kashgar. In 1894 four Swedish missionaries joined him, and a mission base was established. Just one year later they had started a satellite work at Yarkant, about 140 miles (227 km) southeast of Kashgar. In the next few years they also established a Christian witness at Hancheng and Yengisar. From the very beginning the Swedish mission faced great opposition. Ralph Covell notes,

“Local Muslims were infuriated that there was a Christian presence in their sacred territory, and they refused to allow the missionaries to rent any residence. For an extended period they had to live in a garden area, and even then several riots occurred. Finally, the Muslims, together with the Chinese authorities, incited a riot at Easter in 1899.”[4]

The Swedes overcame incessant opposition, and succeeded where no other Protestant mission had done so before. Dozens of Muslims gave their lives to Jesus Christ. Trouble was never far away for the missionaries. In 1924, “a Swedish missionary and his converts were beaten and dragged through the streets of Yarkant.”[5] The Swedes remained at their post, and gradually won over many of the local people with their godly lives and sacrificial service. By 1926 more than 28,000 people had received treatment at the various medical centres established throughout the region. The missionaries provided food during famines, clothed the poor, ran orphanages, and established ten schools. The Bible was translated into Uygur, and the missionaries printed and distributed copious amounts of Christian literature, boldly handing some of it to mullahs and other Islamic clerics. One source records,

“During the years between 1919 and 1939 the adult communicant members of the Christian church of the country grew to number over 200, almost every one a convert from Islam; and if their children be included the Christian community had about 500 members.”[6]

In April 1933 an armed Muslim faction from Khotan took control of Kashgar, Yarkant, and the other towns south of the Taklimakan Desert. Hundreds of Chinese were massacred in the assault, while their wives and daughters were captured and used as sex-slaves or forcibly married off to the deviant attackers, who gained control over most of Xinjiang and proclaimed the Turkish-Islamic Republic of Eastern Turkestan. One of their first objectives was to get rid of the Christian work in Kashgar, Yarkant, and the other places the gospel had taken hold.[7]

On April 27th the Khotan leader, Abdullah Khan, ordered the Swedish missionary Nyström to appear before him. Nyström was in charge of the mission’s medical dispensary, which had benefited thousands of people in Yarkant and surrounding districts. Nyström went to see Abdullah with his colleagues Arell and Hermansson. After being forced to wait a long time at the governor’s mansion,

“The Emir himself came into the room, holding a handkerchief to his nose (to filter the air contaminated by Christian breath). He began to ask such questions as ‘You intended no doubt to use these poisons [medicine] to harm me and my followers?’ Then he yelled, ‘It is my duty, according to our law, to put you to death because by your preaching you have destroyed the faith of some of us! Out with you—bind them.”[8]

The Swedish Mission school in Kashgar in the early 1930s.

After Nyström was bound, the cowardly Abdullah Khan personally struck the defenceless missionary. A group of soldiers armed with rifles, swords, and clubs, told the three missionaries to prepare for instant death. Abdullah Khan raised his sword and was about to start the slaughter when an Indian aide sprang forward and begged for the missionaries’ lives. They narrowly escaped death.

After the initial killings of Christians in 1933, a pause in the persecution occurred as the rebels became deeply engaged in the Civil War. A remarkable turnaround in the fortunes of the missionaries eventuated after Abdullah Khan realized he could use the Swedes' medical skills to treat his wounded soldiers. For several years the mission work continued, and many more Muslims made professions of faith in Christ. The missionaries were finally forced to leave Xinjiang in August 1938. Most returned to Sweden via Russia, while others travelled across the Karokoram Pass into today’s northern Pakistan.

After dealing with the missionaries, the cruel tyrant focused his energies on the local Christians, demonstrating a particular hatred towards all those who had converted from a Muslim background. The male Christians were beaten and thrown into prison at Yarkant and Kashgar. Some were beheaded, while others perished under the terrible tortures. The female Christians (including girls as young as 11) were forced to become wives of Muslim men. One of the girls later said,

“We were called unbelievers, dogs, birds of ill-omen, scum, swine, a shame to our people and accursed…. They said, ‘You must realize that this is being done to save you from damnation. Now say that you will leave your rebellious ways and come back to the faith which was yours in the cradle and which you should never have left.’”[9]

None of the Christian girls said a word, and none denounced their faith. By the start of 1939 at least 100 Christian men suffered martyrdom for their stand for Jesus Christ. Numbered among those who paid the ultimate price for their faith were:

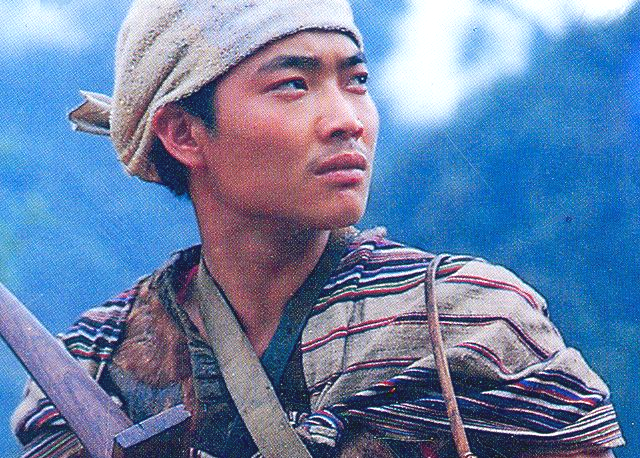

Hassan Akhond of Yarkant, who was 20-years-old. A Muslim friend of his was later released from prison and told how Hassan’s soothing voice had often calmed the nerves of the prisoners at night as he sang hymns to his Saviour. Some nights later they heard him “faintly singing, ‘Loved with Everlasting Love,’ in Uygur. The next two nights [Hassan’s] chain dragged, but after that was silence and they concluded he had died of starvation.”[10]

Almost all of the Christians imprisoned at Kashgar died or were put to death. The Kashgar martyrs included Khelil Akhond, an evangelist from Yengisar, Liu Losi the principal of the Chinese school at Hancheng, and many others. The Christians were herded into groups and then crammed into small, unventilated cells not large enough for each man to even sit down,

“…so that they all spent day and night on end on a half-standing, half-crouching position. The few who survived said they got aches and swelling in their knees and then in the upper part of the calves of the legs and in the thighs. Later mortification usually set in and death followed. These unheated cells were bitterly cold, especially for prisoners who had not been allowed to take with them more clothes than those they stood up in when arrested. A number had been sent to prison only half clad. Some of them were put to unmentionable tortures. Consequently, apart from those who were executed, someone died almost every night, and sometimes four or five corpses were taken out of the cells in the morning. After several years’ imprisonment, when all the leading Christians were dead, the half dozen survivors were admonished with threats and released.”[11]

The gospel had suffered a horrific blow in Xinjiang. After the persecutions of the 1930s the few surviving ex-Muslim Christians faced the horrors of World War II, followed by more than half a century of Communist rule. To the present day there has never been such a widescale turning of Muslims to Christ in Xinjiang as there was when the Swedish Missionary Society was ministering there.

1. Vincent Cronin, The Wise Man from the West (New York: Image Books, 1955), 246.

2. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, 195.

3. An excellent English-language book about Höijer’s life and ministry is by Ann-Charlotte Fritzon, Passion for the Impossible–the Life of the Pioneer Nils Fredrik Höijer (Solna, Sweden: The Swedish Slavic Mission, 1998).

4. Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China, 169.

5. Latourette, A History of Christian Missions in China, 817.

6. R. O. Wingate, The Steep Ascent: The Story of the Christian Church in Turkestan (London: The British and Foreign Bible Society, 1950), 10.

7. An excellent reference documenting the end of the Swedish Mission in Xinjiang is Andrew D. W. Forbes, Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

8. Wingate, The Steep Ascent, 16.

9. Wingate, The Steep Ascent, 19.

10. Wingate, The Steep Ascent, 24.

11. Wingate, The Steep Ascent, 24-25.