© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1342 - The Ili Massacre

June 1342

Ili, Xinjiang

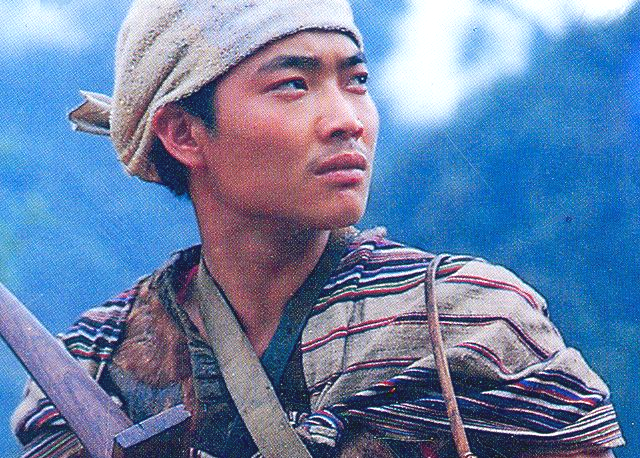

The road to Xinjiang in the early 1900s. Early missionaries spent months traversing such terrain in order to reach Xinjiang.

One of the earliest Catholic missions in China flourished at the most unlikely place—the frontier town of Ili Bâliq (now known as Yining in the Ili Prefecture, Xinjiang). In the 14th century Ili was considered beyond the extent of civilization. Thousands of criminals (and persecuted Christians) were banished there to serve the rest of their lives in exile. An early traveller explained that just to get to Ili required

“…frightful deserts to be traversed, and…mountains and their glaciers to be crossed. These gigantic mountains are, in fact, formed by masses of ice, heaped one upon another, so that travellers can only cross them by cutting steps as they go…. It was among the populations of these great valleys that the Franciscans had succeeded in propagating Christianity.”[1]

The Bishop of Ili was Friar Richard of Burgundy, France. He handpicked some mature brothers from his Order to join him in the remote work. Among them were Francis and Raymond Ruffa, two priests from Alexandria in Egypt, and three laymen: Peter Martel from the French town of Narbonne; Lawrence of Alexandria; and a black man known as John of India. These Christians were pioneer evangelists in the true sense of the word.

“These zealous apostles did not content themselves with residing and preaching in the towns; they were continually traversing the vast extent of Tartary, dwelling, like the nomadic populations of those regions, in huts upon wheels, which carried them across immense tracts of country to wherever the spiritual wants of neophytes [new converts] and the probability of conversions seemed to require their presence. Having no fixed habitation, they followed these pastoral tribes, and adopted their vagabond way of life; stopping with them at their various encampments, living like them upon milk, and glad to pass their days in the Tartar’s tents, if they were only permitted to preach the Gospel to their occupants. What energy and perseverance did these poor monks display!”[2]

If not for the letters of the Spanish missionary-traveller Pascal de Vittoria, little would be known today about the Ili mission. In 1338 Pascal wrote to Pope Benedict XII, recounting the extraordinary opposition he received from Muslims during his journey through Central Asia:

“These children of the devil endeavoured to seduce me by their presents, and promising me voluptuous enjoyments, honour, and riches, all that can be desired of worldly things; they desired to pervert me, and when I repulsed their offers with contempt, they stoned me for two days, singed my face and my feet, tore out my beard, and overwhelmed me with outrage and abuse; but as for me, poor monk as I am, I rejoiced in that the adorable goodness of our Lord Jesus Christ had judged me worthy to suffer these things for his name….

They often administered poison to me, and often plunged me in the water; they fell upon me, and beat me, and inflicted other evils of which I will not speak in this letter. But I thank God for all, and I hope to suffer more still for the glory of his name.”[3]

Soon after the Franciscans arrived, the Prince of Ili fell ill. Francis of Alexandria had some experience as a surgeon, and he succeeded not only in helping the prince recover, but also in winning the confidence and favour of the prince and his father, the Khan. For several years the missionaries were granted freedom to preach the gospel anywhere within the realm, but this came to an abrupt end in 1342 when the Khan was poisoned by one of the princes who was a fanatical Muslim. The murderer usurped the throne and immediately issued an edict ordering all Christians to renounce Jesus Christ and embrace Islam. Failure to do so would result in death. The Christians, however,

“…had the honour and courage formally to refuse obedience to the tyrant, and took no notice of his menaces. They publicly professed their faith, and continued to celebrate as before the ceremonies of their religion; and the usurper being informed of this noble and holy rebellion, gave orders that the means of seduction should first be tried, with respect to both the missionaries and their converts, but that, should these fail, the Christians should be pitilessly exterminated.”[4]

At the time there were seven missionaries serving at Ili. They were arrested, chained together, and made to stand before a furious Muslim mob.

“They began by abuse, then they struck the missionaries on the head and with whips and sticks,—then they stabbed at them, and finally cut off their noses and ears; and when they found that neither opprobrium nor torment could shake the constancy of these valiant apostles, whose voices rose high amidst their tortures to glorify Jesus Christ, to preach the Gospel, and to utter anathemas on Mohammed and the Qu’ran,—they struck their heads off.”[5]

The cruel massacre of the Franciscans occurred in June 1342. As soon as the missionaries were out of the way the bloodthirsty mob descended on the convent, pillaging everything of value before setting it ablaze.

The local Christians—who included ethnic Uygurs, Kazaks, Mongols, Russians and Han Chinese—refused to flee from their homes. They were thrown into prison and tortured with barbaric cruelty. Many Ili Christians died as martyrs. Those who survived the torment were eventually released after the tyrant ruler was overthrown and put to death by a Mongol chief.

The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that Ili was not the only place where Catholics were persecuted around this time. It states, “The first Christian martyrs in China appear to have been the missionaries of Ili Bâliq in Central Asia [Xinjiang], Khan- Bâliq [Beijing] and Zaitun [Fujian] in the middle of the fourteenth century…the Hungarian, Matthew Escandel, being possibly the first martyr.”[6]

Despite being deprived of leadership and direction, the Church in Ili survived against all odds after the 1342 massacre. Remarkably, more than four hundred years later, the gospel was still being preached in this remote outpost. In 1771 thousands of Torgut Mongols fled into China from their homes in Russia, where the Orthodox Church had harassed them. One source notes,

“When they arrived in the Ili valley they found another form of Christianity. The Franciscans had established a Christian center called Ili Bâliq there from as early as the fourteenth century…. They had built a magnificent church. Ili later became the Gulag of China, to which criminals were banished and to which Chinese Christians who refused to apostatise were sent.”[7]

1. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, 409.

2. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, 409-410.

3. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, 412-413.

4. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, 415.

5. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, 415.

6. The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IX, online edition at www.newadvent.org

7. Hugh P. Kemp, Steppe By Step: Mongolia’s Christians – From Ancient Roots to Vibrant Young Church (London: Monarch Books, 2000), 249.