Introduction to Tibet

The Land of Snows

Tibet—the name itself sends a shiver down the spine of many people. Mysterious, forbidden, unreachable; for centuries Tibet has been the desire of explorers, pilgrims, armies and missionaries alike, but its seemingly impenetrable barriers have been slow to yield any treasures to those who seek them.

The extraordinary walls of rock and ice that surround Tibet have successfully protected it from most outside influence. Sitting at an average altitude of 14,800 feet (4,500 meters) above sea-level, Tibet's physical challenges were vividly summed up by the French Catholic missionary Auguste Desgodins in the early 1860s:

"Take a piece of paper in your hand. Crumple it up and then open your hand and let it fall out! Nothing is flat—all you have are high points and low depressions—the steep, inaccessible, rugged mountains and the deep valleys, through which flow some of the largest and fastest rivers in the world."

The sheer size of Tibet is astonishing, and it is home to a total Tibetan population in China of 6.28 million people, according to the 2010 census. The present-day Tibet Autonomous Region alone covers an area of 474,300 square miles (more than 1.2 million sq. km). When Tibetan areas now in the Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai and Yunnan are included, the overall area inhabited by the Tibetan people in China increases to approximately 750,000 square miles (1.94 million sq. km).

To help us comprehend the vastness and emptiness of Tibet, the area inhabited by Tibetans in China is almost three times larger than Texas, but with one-fourth as many people as the Lone Star State. By another measure, Tibet is also roughly three times the size of the United Kingdom, but the UK has a population ten times larger.

A Turbulent History

Much of the ancient history of Tibet is clouded in myth, but it is known that nomadic tribes inhabited parts of the Tibetan Plateau as early as the second century BC.

The seventh and eighth centuries AD saw the emergence of a large Tibetan empire, during a period considered the 'golden age' of its history. Tibetan influence at the time extended into north India, Nepal, Bhutan and northern Myanmar; and frequent armed conflicts took place with the Chinese along Tibet's eastern and northern borders. In 763, a Tibetan army even managed to lay siege to and destroy China's capital city of Xi'an.

As the centuries went by, China's rulers began to eye the open spaces and natural resources of the Tibetan Plateau, and military campaigns were launched to bring the country under Chinese rule for the first time. A pivotal moment occurred in 1720, when the Chinese tore down the walls of Lhasa, stationed thousands of troops throughout central Tibet, and annexed a large part of the Kham region into Sichuan Province. Later, India and the independent kingdoms of Sikkim and Ladakh also laid claim to parts of Tibet. In addition, Mongolia and Russia increased their focus on the Roof of the World, and Tibet gradually emerged as the stage for a grand tug-of-war between competing powers.

In 1903, a British expeditionary force under the command of Francis Younghusband invaded Tibet. The Tibetan army was hopelessly outmatched against the superior British technology, and in one skirmish more than 600 Tibetans were mowed down by Maxim machine guns. The Thirteenth Dalai Lama fled to Mongolia, where he remained for four years, but when the Chinese invaded Lhasa in 1910 he fled across the Himalayas to northern India, in a foreshadowing of the events that would follow the Fourteenth Dalai Lama several decades later.

The Dark Powers of Bon

Although on the surface, the overwhelming majority of Tibetans claim to be Buddhists, many observers have come to realize that Buddhism is merely a veneer placed over the ancient, all-encompassing foundation of Chö, a Tibetan belief system that includes "all phenomena, all matter, and everything that can be known.... The Tibetan Buddhist view of the world is not divided into compartments, but takes in all of life at once. Chö and life are inseparable."

Long before Buddhism arrived on the Tibetan Plateau from India in the seventh century AD, the powerful religion of Bon had prevailed for countless generations. Bon is an ancient shamanistic worldview, where dark occult practices intertwine with demonic possession and meta-physical events, creating a layer of spiritual darkness that centuries of Christian endeavour have so far failed to penetrate.

Belief in the powers of the unseen world is reinforced in each new generation of Tibetans through their stories and literature, "which are filled with tales of the fantastic and the bizarre. Flying demons, monks who change their appearance at will, powerful lamas who force disembodied minds into dead bodies, and a host of other strange tales are part of the literary heritage of Tibet."

Many Westerns claim that after the Communist armies swept through Tibet, crushing hordes of people and demolishing their culture, the Chinese had cruelly dismantled an idyllic and peaceful society, but it would be remiss to ignore the fact that Tibetan society had deteriorated to such a low ebb by the 1950s that sexual disease and abuse was rampant, and millions of Tibetans were enslaved by an oppressive dictatorship.

The Strong Man of Tibet

The spiritual realm is so real in Tibet that peoples' daily lives are intertwined with and often appear inseparable from the forces of darkness. For example, most Tibetans know that the real head of state of the Tibetan people is not the Dalai Lama, but the State Oracle—an individual who is possessed by a demonic spirit called Nechung. Thubten Ngodup, a man who was born in Tibet in 1957, serves as the State Oracle and also has a seat as a deputy minister in the Tibetan government in exile.

The Dalai Lama himself has left little doubt about the role demonic entities play in the authority structures of Tibet. In his autobiography, Freedom in Exile, the Dalai Lama wrote:

"In former times there must have been many hundreds of oracles throughout Tibet. Few survive, but the most important—those used by the Tibetan government—still exist. Of these, the principal one is known as the Nechung oracle. Through him manifests Drak-den, one of the protector divinities of the Dalai Lama....

For hundreds of years now, it has been traditional for the Dalai Lama, and the government, to consult Nechung during the New Year festivals. In addition, he might well be called upon at other times if either have specific queries. I myself have dealings with him several times a year.... I seek his opinion in the same way as I seek the opinion of my cabinet and just as I seek the opinion of my own conscience. I consider the gods to be my 'upper house'....

In one respect, the responsibility of Nechung and the responsibility of the Dalai Lama towards Tibet are the same, though we act in different ways. My task, that of leadership, is peaceful. His, in his capacity as protector and defender, is wrathful. However, although our functions are similar, my relationship with Nechung is that of commander to lieutenant: I never bow down to him. It is for Nechung to bow to the Dalai Lama. Yet we are also very close friends."

This insight should be startling to all Christians. The Bible teaches us that "our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms" (Ephesians 6:12). The Dalai Lama here has stated that not only does a powerful demonic ruler exist over Tibet, but it is embodied within a man who holds a position in the government, and who is often consulted for guidance and advice!

What many Tibetans consider normal within their worldview has often been labelled as nonsense by materialist Westerners, and accounts of the stark reality of the spirit world in that land are dismissed. However, during the times when the two cultures have collided, Western onlookers have been left speechless and afraid of what their eyes have seen and their ears have heard.

Many are the stories of dark arts practised by Tibetan shamans and lamas, but hopefully the examples below will suffice to give readers a brief glimpse into the powerful spiritual forces that have bound the people of Tibet for thousands of years:

On one occasion, Australian missionary-doctor Allan Maberly was giving injections to a group of Tibetan refugees from Kham. He recalled, "Three times I plunged the needle into one man's arm only to find the skin like stone, which bent the needle. The Tibetan suddenly remembered that his 'magic' stone was still on his belt, so he removed it and handed it to a friend. On the next try the muscle was soft as cheese and the needle went in smoothly!"

In 1981, an American camera crew traveled to north India to film the cremation of a famous Tibetan lama. The disbelieving crew reported seeing "the top of the lama's skull fly up into the air without coming down to earth. Later during the cremation, the lama's eye, tongue, and heart supposedly flew out of the fire and fell at the feet of another monk. The local Tibetans took all these 'miracles' in a matter of fact way."

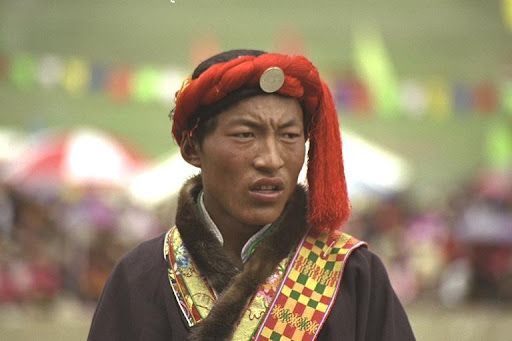

The Three Regions of Tibet

Throughout its long history, Tibet was traditionally home to three main regions, with additional kingdoms and principalities within each. Although the branches of the Tibetan race have been unified in many ways by their common culture and religious adherence, significant differences still exist between Tibetans in terms of history, customs and language.

Many of the chapters in this book have been divided into sections according to the historic region of Tibet in which the described events took place. It is useful to summarise each of the three regions of Tibet, as follows:

Ü-Tsang དབུས་གཙང་

Although the Tibetan authorities like to portray Tibetans as one unified people and language, linguistic studies have found that the standard Lhasa Tibetan language shares an 80 percent lexical similarity with Kham Tibetan, and a 70 percent similarity with Amdo. By way of comparison, English and German reportedly share a 60 percent lexical similarity. Tibetan travelers from different regions often struggle to communicate with each other in their respective languages.

Ü-Tsang has long been considered the hub of Tibetan civilization, and is often referred to in English as "central Tibet". It was formed long ago when the provinces of Ü (based at Lhasa) and Tsang (Xigaze) were combined.

The name Ü-Tsang was actually artificially derived from Qing Dynasty maps, which designated Ü (Lhasa) where the Dalai Lama had his throne as "Front Tibet," and Tsang (where the Panchen Lama was based) as "Back Tibet." In reality, however, the Dalai Lama exercised effective rule over both regions and in Tibetan minds there is little difference.

Linguistically and culturally, however, there are distinctions between Central Tibet and the Kham and Amdo regions. For the purposes of this book, Ü-Tsang is used to describe Central Tibet, which contains around 45 percent of Tibetans in China today, and is hemmed in by its borders with India, Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar.

Founded in AD 633, Lhasa, which means 'land of the gods' or 'holy place' in Tibetan, stands at a lung-busting 12,330 feet (3,660 meters) above sea-level, and has long been considered the seat of Tibetan Buddhism, similar to the position that Mecca holds in Islam or Rome in Catholicism. Lhasa's skyline is dominated by the thousand-room Potala Palace, the former abode of the Dalai Lama. The Jokhang Temple, a mile to the east of the palace, is considered the spiritual heart of the city.

Lhasa remains the goal of most visitors to Tibet, including tens of thousands of Westerners who flock to the city in an attempt to satisfy their spiritual longings. Early travelers would have been astonished to learn that Lhasa would one day be seen as a place of pilgrimage for tourists, because for much of its history it was a dirty, run-down town with little going for it. Thomas Manning provided this grim description of Lhasa in the early 1800s:

"There is nothing striking, nothing pleasing in its appearance. The habitations are begrimed with smut and dirt. The avenues are full of dogs, some growling and gnawing bits of hide which lie about in profusion, and emit a charnel-house smell; others limping and looking livid; others ulcerated; others starving and dying, and pecked at by the ravens; some dead and preyed upon. In short, everything seems mean and gloomy."

Situated to the west of Lhasa, the massive Ngari Prefecture is an arid wasteland, and is also rumored to be home to many of China's nuclear weapons. Scattered throughout Ngari are the ruins of long-abandoned civilizations that once flourished in the area, including the Guge kingdom, which dominated trade and commerce between India and China until its sudden demise in 1630.

Intrepid travelers to remote parts of Ngari sometimes encounter Tibetans so isolated that they have never seen an outsider before. This had led to some uncomfortable exchanges, such as an incident in the 1980s when an Australian tourist tried to watch a Tibetan 'wind burial,' where human corpses are cut into small pieces and laid on an exposed rock for vultures and ravens to devour. The tourist attempted to hide while using a telephoto lens to take photographs of the grisly scene, but

"While hopping around on the skyline, he scared the birds away—an exceptionally evil omen. The irate burial squad gave chase, brandishing knives, and showered him with rocks. Another group of tourists were bombarded with rocks, chased with knives, or threatened with meaty leg-bones ripped straight off the corpse."

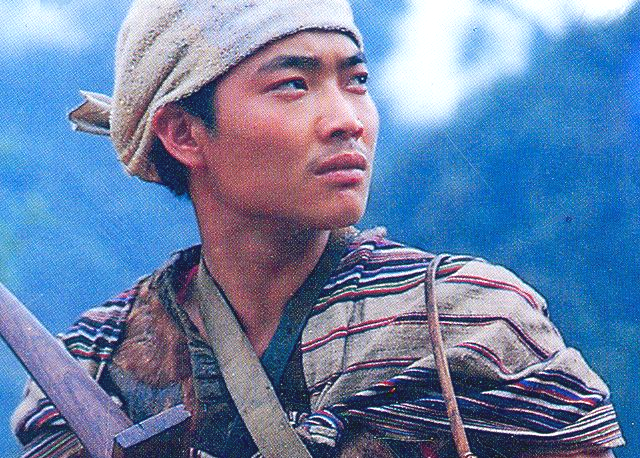

Filled with deep river valleys and snow-capped peaks, Kham is the traditional southeastern region of Tibet, and the homeland of fearsome Khampa warriors—skilled horsemen who guarded the eastern Tibetan frontier and kept out unwanted visitors.

For centuries, outsiders have been terrorized by the tall Khampa men—many are over 6 feet in height—as they are known for their fierceness and indiscriminate killings. Heinrich Harrier walked through Kham areas in the 1940s, giving this description of the people in his famous book Seven Years in Tibet:

"They live in groups in three or four tents which serve as headquarters for their campaigns.... Heavily armed with rifles and swords they force their way into a nomad's tent and insist on hospitable entertainment on the most lavish scale available. The nomad in terror brings out everything he has.

The Khampas fill their bellies and their pockets and, taking a few cattle with them for good measure, disappear into the wide open spaces. They repeat the performance at another tent every day till the whole region has been skinned.... Stories were told of the cruelty with which they sometimes put their victims to death. They go so far as to slaughter pilgrims and wandering monks and nuns."

Throughout its history, Kham was never fully under the control of the Dalai Lama, but was home to more than 30 independent Tibetan kingdoms and principalities, each with its own royal family. Today, approximately 26 percent of Tibetans in China live in the Kham region, which comprises areas in today's Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu provinces.

Kham was gradually integrated into China's Sichuan Province beginning in 1720. The People's Liberation Army completed the job in the 1950s, with their tanks rolling across Kham and leaving a trail of death and destruction in their wake.

Amdo ཨ་མདོ་

Amdo Province is the traditional northeastern region of Tibet, and is home to approximately 29 percent of Tibetan people in China.

Some Amdo areas are so remote that nomads in those parts continue to live with scant knowledge of the outside world. Little has changed since the late 1920s, when a visitor wrote: "A miserable land it is, of poverty and incredible filth; a land cut off from the modern world, a region which, for uncounted centuries, has had its own forms of government, of religion and social customs."

The most famous landmark in Amdo is the massive salt-water Qinghai Lake, which was traditionally known by its Mongolian name Kokonor. The largest lake in China, it's azure waters and backdrop of snow-capped mountains make it a favorite destination for breathless travelers, many of whom struggle with the lack of oxygen as the lake sits 10,515 feet (3,205 meters) above sea-level.

Beyond the lake, a huge expanse of lush grasslands and mosquito-infested swamps stretch for hundreds of miles, while access to central Tibet is blocked by the Amne Machen mountain range, with its razor-like peaks rising to an imposing elevation of 20,610 feet (6,282 meters).

The Amdo region is home to an abundant variety of wildlife including bears, deer, gazelles and wolves, while among its many fascinating ethnic groups are the Golog people, a name meaning "those with heads on backwards" in reference to their rebellious nature.

Amdo was incorporated into the Chinese provinces of Qinghai and Gansu between 1928 and the 1950s. Among the Amdo people there are several major linguistic divisions, which scholars have labelled according to the primary occupations of their speakers, such as Hbrogpa (meaning 'nomad' or herder' in Tibetan); Rongba ('farmer'); and Rongmahbrogpa, which is an amalgamation of the two.

While today the Chinese government recognizes just a handful of ethnic groups in the Amdo region, researchers during the first half of the 20th century compiled a huge list of tribes, clans, self-governing principalities and people groups in Amdo. One source said:

"In the 1930s there were about 600 ethnic groups in Amdo. The political structure can be roughly described as a regionally variable mixture of large estates or small kingdoms with inherited titles and powers, towns built up around major monasteries, and open, unsettled territories claimed by groups of nomads."

Padmasambhava, an eighth century Tibetan sage, is reputed to have spoken the following prophecy: "When the iron bird flies and horses run on wheels, the Tibetan people will be scattered like ants across the world and the Dharma will come to the land of the Red Man."

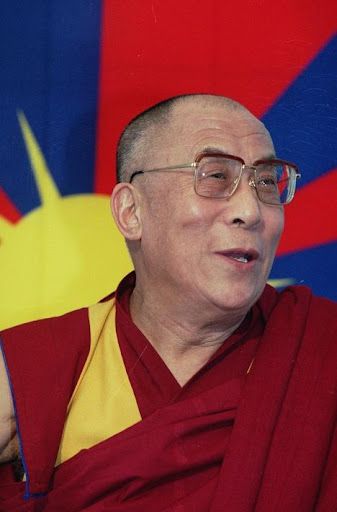

In an apparent fulfilment of this prophecy, in 1959 the Chinese army invaded Tibet and was approaching the outskirts of Lhasa. Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, fled across the Himalayas to India, where he has continued to lead a Tibetan 'government in exile'.

In the six decades since his departure, the Dalai Lama—a Mongolian term meaning 'ocean of wisdom'—has risen to worldwide prominence, and today millions of people around the globe consider him one of the world's great figures. He is much loved and respected by presidents, kings and nomads alike. He has won the Nobel Peace Prize, and is regarded as a god-king by some and a freedom fighter by others. This smiling monk from an Amdo farming family has become the undisputed darling of Hollywood, while at the same time he is despised as a trouble-maker and separatist by the Communist rulers of China.

Many Christians seem confused about how they should view the Dalai Lama, but New Zealander Hugh Kemp, who has met the Dalai Lama on several occasions, has sounded a warning bell to Christians about the insidious danger lurking behind Tibetan Buddhism and the teachings of its god-king:

"To the present generation of Westerners, who reject moral absolutes and despise any claim to spiritual exclusivity, it is no wonder the Dalai Lama is so popular. I've heard the Dalai Lama say, with a casual wave of his hand, 'If you think my message is nonsense, then forget it.' Thanks, I think I might, and I'll stick with Jesus, the true incarnation of God."

In relation to Jesus Christ and Christianity, the Dalai Lama has long touted a universalist worldview, insisting that no religion is better than another, and no one can claim to know the truth. He has stated:

"All religious teachers have beauty and unity. Jesus was a manifestation of Buddha.... Jesus was a Great Master.... Whether we can say there is one truth, one religion, or several religions...this concept is difficult.... Religion is like medicine. One particular illness needs one particular medicine to be effective."

William of Rubruck

Uniquely, the honor of being the first known Western visitor to comment on Tibet and its customs does not belong to Marco Polo, who visited eastern Tibet in the 1270s.

A few decades earlier, William of Rubruck (c. 1220-93), a Franciscan missionary and explorer from the Fleming region in what is now Belgium, commenced an epic journey to the Orient. After setting out from today's Istanbul in May 1253, William traversed the Central Asian steppes and visited China, where he interacted with leaders of the Mongolian empire, before beginning the long journey home in July 1254. William's report to King Louis IX of France included references to Nestorian Christians he had met in the Mongolian court. This thrilled believers back in Europe, who assumed that no trace of the Christian faith would be found in the distant barbarian lands.

During his journey, William collected stories about the people of "Tebec." He wrote of Tibetan warriors and their brave attempts to hold off Genghis Khan's armies in battle, and provided an account of yaks on the Tibetan Plateau. William wrote:

"Next come the Tebec—men whose custom it was to eat their deceased parents as to provide them, out of filial piety, with no other sepulchre except their own stomachs. They have stopped doing this now, however, for it made them detestable in the eyes of all men. Nevertheless they still make fine goblets out of their parents' skulls so that when drinking they may be mindful of them in the midst of their enjoyment....

They have a good deal of gold in their country, so if anyone needs any he digs until he finds it, and he takes as much as he needs, putting the rest back into the ground, for he believes that if he were to place it among his treasures or in a box, God would take away from him all that is in the earth."

Marco Polo and the 'People of Tebet'

The next glimpse Europe had of Tibet came from the pen of the intrepid Marco Polo, who ventured into the Kham region from the city of Chengdu in the 1270s as an emissary of the Mongol rulers. It appears that Polo traveled a considerable distance into Greater Tibet, through parts of today's western Sichuan Province, before turning south into northern Yunnan and regions beyond, which he called Caindu. His vivid descriptions captured the imagination of astonished Europeans.

Polo wrote about departing Chengdu and riding through an area surrounded by snow-capped mountains, past numerous villages that had been completely destroyed by the Mongol hordes a few decades earlier. Polo and his escorts rode for 20 days through uninhabited terrain, "so that travelers are obliged to carry all their provisions with them, and are constantly falling in with those wild beasts which are so numerous and dangerous. After that you come at length to a tract where there are towns and villages in considerable numbers."

Marco Polo appeared to be troubled by some of the Tibetan customs he encountered, especially the rampant sexual immorality among the people—an aspect of life that has changed little among Tibetan nomads over the ensuing eight centuries. He wrote:

"A scandalous custom, which could only proceed from the blindness of idolatry, prevails among the people of these parts, who are disinclined to marry young women so long as they are in their virgin state, but require, on the contrary, that they should have had previous commerce with many of the other sex. This, they assert, is pleasing to their deities, and they believe that a woman who has not had the company of men is worthless....

In this manner people traveling that way, when they reach a village or hamlet or other inhabited place, shall find perhaps 20 or 30 girls at their disposal.... It is expected, however, that the merchants should make them presents of trinkets, rings, or other complimentary tokens of regard, which the young women take home with them. They wear all these ornaments about the neck or other part of the body, and she who exhibits the greatest number of them is said to have attracted the attention of the greatest number of men, and is on that account held in higher esteem with the young men who are looking out for wives.

At the wedding, she accordingly makes a display of them to the assembly, and she regards them as a proof that their idols have rendered her lovely in the eyes of men."

The great explorer also remarked: "The people are idolaters and an evil generation, holding it no sin to rob and maltreat: in fact, they are the greatest brigands on earth.... This province, called Tebet, is of very great extent.... The country is, in fact, so great that it embraces eight kingdoms, and a vast number of cities and villages."

Polo also described the dark arts of the people he met in Tibet: "Among these people you find the best enchanters, who by their infernal art perform the most extraordinary and delusive marvels that were ever seen or heard. They cause tempests to arise, accompanied with flashes of lightning and thunderbolts, and produce many other miraculous effects. They are altogether an ill-conditioned race."

Later, when he had reached the Mongol court at today's Beijing, Polo noted the power of the Tibetan sorcerers whom the Great Khan had brought to the capital. He wrote that Tibetan astrologers could control the weather over the summer palace, and described one of the acts performed by these men:

"When the Great Kaan is at his capital and in his great palace, seated at his table, which stands on a platform some eight cubits above the ground, his cups are set before him on a great buffet in the middle of the hall pavement, at a distance of some ten paces from his table, and filled with wine, or other good spiced liquor such as they use. Now when the Lord desires to drink, these enchanters by the power of their enchantments cause the cups to move from their place without being touched by anybody, and to present themselves to the Emperor! This everyone present may witness, and there are oft-times more than 10,000 persons thus present."

In reflecting upon the supernatural abilities of the Tibetans, Polo concluded: "Whatever they do in this way is by the help of the devil, but they make those people believe it is compassed by dint of their own sanctity and the help of God. They always go in a state of dirt and uncleanness, devoid of respect for themselves or for those who see them, unwashed, unkempt, and sordidly attired."

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book ‘Tibet: The Roof of the World’. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. Cited in Ralph R. Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China: The Christian Faith Among China's Minority Peoples (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1995), p. 33.

2. For those interested in learning more about Tibetan history, an attractive new book on the historical composition of Tibet is Karl E. Ryavec, A Historical Atlas of Tibet (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015). Another good contemporary history of Tibet is Sam Van Schaik, Tibet: A History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

3. Today, hundreds of thousands of Tibetans consider themselves adherents of Bon, and many Bon monasteries and monks are still found scattered throughout the Tibetan world.

4. Marku Tsering, Sharing Christ in the Tibetan Buddhist World (Upper Darby, PA: Tibet Press, 1988), p. 98.

5. Tsering, Sharing Christ in the Tibetan Buddhist World, p. 99.

6. Dalai Lama XIV, Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama (New York: Harper Collins, 1991), pp. 211-12.

7. For example, A well-publicized incident took place in 1937, when Harrison Forman—a staunch American atheist with a background in science and research—was widely mocked by his report of a religious ceremony he observed in the Golog Tibetan area, which left him shocked and terrified. Forman described watching a Bon monk and his followers as they called on Yama, the King of Hell, until the fearsome spirit visualized in front of them. See Forman, "I See the King of Hell," Reader's Digest (December 1937).

8. Allan Maberly, God Spoke Tibetan: The Epic Story of the Men Who Gave the Bible to Tibet, the Forbidden Land (Orange, CA: Evangel Bible Translators, 1971), p. 135.

9. Tsering, Sharing Christ in the Tibetan Buddhist World, pp. 99-100.

10. Although the Tibetan authorities like to portray Tibetans as one unified people and language, linguistic studies have found that the standard Lhasa Tibetan language shares an 80 percent lexical similarity with Kham Tibetan, and a 70 percent similarity with Amdo. By way of comparison, English and German reportedly share a 60 percent lexical similarity. Tibetan travelers from different regions often struggle to communicate with each other in their respective languages.

11. Michael Buckley and Robert Strauss (eds.), Tibet: a Travel Survival Kit (Hawthorn, Australia: Lonely Planet Publications, 1986), p. 23.

12. Buckley and Strauss, Tibet: a Travel Survival Kit, p. 141.

13. Heinrich Harrer, Seven Years in Tibet (London: Pan Books, 1953), p. 94.

14. Joseph Rock, "Seeking the Mountains of Mystery," National Geographic (February 1930), p. 131.

15. Galen Rowell, "Nomads of China's West," National Geographic (February 1982), p. 244.

16. Paul Kocot Neitupski, Labrang: A Tibetan Monastery at the Crossroads of Four Civilizations (Boulder, CO: Snow Lion Publications, 1999), p. 16.

17. Buckley and Strauss, Tibet: a Travel Survival Kit, p. 9.

18. Adapted from Hugh P. Kemp, "The 14th Dalai Lama: a 'Simple Monk' or a god?" in Paul Hattaway, Peoples of the Buddhist World: A Christian Prayer Guide (Carlisle, UK: Piquant, 2004), p. 166.

19. Kemp, "The 14th Dalai Lama," in Hattaway, Peoples of the Buddhist World, pp. 164-65.

20. Christopher Dawson, The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1955), p. 142.

21. Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition, Vol. 2 (New York: Dover Publications, 1903), pp. 43-44.

22. A 1950s survey of the Khampa Tibetan areas "found the rate of venereal diseases was 40% in peasant areas and 50.7% in pasture areas," cited in Paul Hattaway, Operation China: Introducing all the Peoples of China (Carlisle: Piquant Books, 2000), p. 631.

23. Manuel Komroff (ed.), The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian (New York: Horace Liverlight, 1926), pp. 188-89.

24. Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo, Vol. 2, p. 45.

25. Komroff, The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian, p. 190.

26. Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition, Vol. 1 (New York: Dover Publications, 1903), pp. 301-302.

27. Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo, Vol. 1, p. 301.