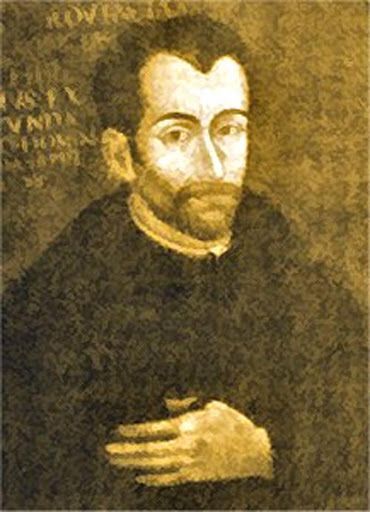

Antonio de Andrade and the Kingdom of Guge

Born in Portugal in 1581, Antonio de Andrade was the key figure in a remarkable attempt to introduce Christianity to Tibet, only for his efforts to be mercilessly snatched away when seemingly on the cusp of great success.

Andrade entered the Jesuit order at the age of 16, and three years later was sent to the Portuguese colony of Goa in south India to complete his training.

Andrade, accompanied by Manuel Marques, traveled to Delhi where they met a group of Hindus who were planning to cross the Himalayas into Tibet. The zealous missionaries decided to go with them, and in March 1624, disguised as Hindu pilgrims, they "outwitted hostile local officials, made their way north into the Himalayas, endured altitude sickness and snow blindness, and fought their way over a 17,900-feet [5,456 meter] pass into Tibet."

Traversing the Himalayas was an extraordinary challenge, as Andrade's 31-page journal made clear. Poorly equipped for the intense hardship and bitter cold, the vivid descriptions of the journey help explain why Christianity has struggled to gain a foothold in Tibet throughout history. He wrote:

"We began to climb these lofty mountains, which have not their like perhaps on the surface of the globe. It took us two days' march to cross one. In some places the passage between them is so narrow that we could only just put one foot before the other, and for a long way we had to go first on one side and then on the other, clinging to the rocks with our hands, and at a single false step we should have been dashed to pieces."

Swimming on the Snow

Andrade described another harrowing section of the journey: "Immediately beyond this place there rise lofty mountains, behind which lies an awful desert, which is passable only during two months of the year. The journey requires 20 days. As there is an entire absence of trees and plants here, there are no human habitations, and the snowfall is almost uninterrupted."

Passing through the desert caused the Portuguese priest to despair of his life. He wrote:

"We plunged into the desert and struggled on with difficulty, sometimes up to our waists in snow, sometimes up to our shoulders, and never less than knee deep. Occasionally we dragged ourselves at full length along the surface of it, as if we were swimming. Such were the labors of the day, and the night brought us little rest. We spread our cloaks upon the snow, and covered ourselves as well as we could with others, but very frequently the snow fell so thick upon us that we were obliged to rise and shake it off that we might not be buried. The cold was so severe, that we had lost all feeling in various parts of the body—principally the hands, feet, and face.

Once when I tried to hold something, a bone came out of one of my fingers, but I was not aware of it till I saw the blood on my hand. Our feet were so swelled and numbed, that if a hot iron had touched them we should not have felt it."

When Andrade's report of his journey to Tibet made its way back to Europe, most people thought it was a work of fiction, or a scurrilous account of exaggeration and lies. Tibet appeared as an empty space on maps at the time, and many years passed before later travellers confirmed the veracity of Andrade's account. To cross the Himalayas once on foot is more than most people can endure, but incredibly, Andrade completed the journey several times as he sought to establish God's kingdom on the Roof the World.

The Wealthiest City in Asia

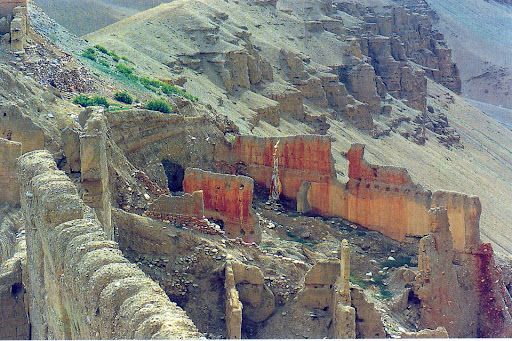

Andrade and his colleagues struggled on for weeks, until they finally reached Zaburang, the capital of the ancient Guge kingdom in northwest Tibet. Sitting at 14,760 feet (4,500 meters) above sea-level, the oxygen content in the air is only about one-third of teh amount at sea-level.

The Guge kingdom—which covered an area twice the size of the United Kingdom—had long been a crucial location in the Tibetan world. Founded in the first half of the tenth century, Guge was ruled for more than 700 years by 28 lineal kings.

In 1042 the king of Guge invited the great Indian scholar Atisha to visit Tibet. Later, when many leading Buddhist monks and artisans were persecuted by Muslims in north India they fled to Zaburang, causing it to grow into perhaps the wealthiest city in Asia. It contained some of the best art in the world, copious amounts of jewelry, and many gold mines.

The palace at Zaburang was located at the top of a sheer cliff, the height of an 80-storey skyscraper. The Guge royal family and the wealthy lived in the citadel at the top of the cliff, with peasants and laborers dwelling on the valley floor far below. Buddhist monks resided in the middle. The only way to the top of the mountain was via a narrow stairway that allowed only one person at a time to ascend. This palace obtained water via two wells that extended 200 feet (61 meters) down into the mountain, while storerooms were stocked with food and almost a thousand firearms. The fort was near impregnable, and had helped the kingdom of Guge repel invading armies.

A Warm Welcome

The party of travelers had been decimated by the rigors of the journey across the mountains and desert, and was reduced to just three sick and exhausted men who stumbled toward Zaburang. The local Guge rulers, astonished that these poorly-equipped people had managed to cross the Himalayas with few supplies, sent soldiers on horseback to intercept the travelers. Andrade was afraid they had been dispatched to arrest the party, but the soldiers gave them barley, honey and some furs to protect them from the bitter cold. A guide was provided to help bring the men safely to their destination. King Chadakpo of Guge also supplied horses to carry them on the final three days journey to Zaburang. Andrade recalled:

"At our entrance into the town the people thronged around us, and the women rushed to the windows to gaze at us, as if we had been wonderful curiosities.

The king did not show himself, but the queen was upon a kind of balcony of her palace as we passed, and we bowed profoundly to her, and then went on to a house that was ready to receive us. The king imagined we were merchants, and that we had brought him some valuable jewels, and could not conceive that any motive but the desire of gain could have tempted us to undertake so painful a journey....

He inquired what the real motive of our journey was, and I replied that we had not come to Tibet to buy or to sell, since we were not traders; that I was very grateful for the favors that had been granted me, and I earnestly begged for an hour's audience, during which I would explain to him the reasons that had brought me to his dominions. I assured him beforehand they were such as would give him great satisfaction."

An Enduring Friendship

King Chadakpo received Andrade with great kindness and hospitality. The missionary spoke with the king in Persian, which was interpreted into Tibetan by a Muslim from Kashmir. Chadakpo appeared to comprehend little of what Andrade said, and later conversations caused Andrade to suspect that the Muslim was not accurately conveying his words. When the king was informed of Andrade's concerns, the interpreter was dismissed and a more honest replacement was found. King Chadakpo was also made aware of the slanders that Muslims had spread regarding Christianity, and he promised he would be wary of anything the Muslims told him from that point forward.

The queen of Guge soon emerged as a key figure in Andrade's mission. At the start, whenever the king met with the missionaries, the queen hid herself behind a curtain and listened intently. Overcome with curiosity, she sent a note to her husband saying she must see these men and soon made her appearance, asking many questions about their faith. She was present in all the subsequent audiences granted to the missionaries.

God's favor rested on Andrade, and he was allowed to present himself at court whenever he wished. The king also gave him an abundant daily allowance of provisions, consisting of rice, mutton, flour, butter, grapes, and wine, which had been imported from a fertile valley 12 days' journey from Zaburang.

After receiving such a strong welcome, Andrade might have been tempted to stay in Tibet, but mindful that the passes back to India would soon be blocked again by snow, he prepared to depart, after promising the king he would return to Guge the following year. King Chadakpo gave a remarkable letter to Andrade, which said:

"I, king of the great kingdom of Tibet, having felt great pleasure at the arrival of Antonio de Andrade, a Portuguese, to teach the holy law in our dominions, and regarding him as our master, grant to him full and perfect liberty to preach freely and teach our people the said law, and we forbid all persons from disturbing him in its exercise.

I command, moreover, that a piece of ground shall be given to him whereon to build a church. We consent that if there should arrive in our country any foreign merchants, the said religious man and his companions shall take no part in their traffic, in order that they may do nothing that might be incompatible with the dignity of their functions.

We promise, besides, to give no credit to any reports that may be raised concerning them by the Muslims, being very sure that they who follow a law full of errors would find a sweet satisfaction in vexing those who profess the true religion.

We furthermore most earnestly solicit the Grand Provincial of India to send us de Andrade again, that he may instruct our subjects."

Andrade commenced his journey across the Himalayan divide; this time escorted by soldiers and loaded down with provisions. He reflected on the amazing events that had unfolded, and was confident that many Tibetans would soon become followers of Jesus Christ. He wrote:

"It is easy to see that the king and his court were sorry for our departure; and in bidding us farewell, he reminded us that we were to come again as soon as possible, because we 'carried his heart with us'. He had us escorted not only to the frontiers of his kingdom but even across the desert, and gave orders privately that we should be everywhere provided with as much meat, rice, and butter as we required. Three days after our departure we were overtaken by three men, who brought us from the king some baskets containing more than 1,000 peaches, which, though small, were of extremely pleasant flavor."

After Andrade and his companions reached the Jesuit base in India, the other missionaries were filled with excitement, and many volunteered to accompany him to Tibet the following year. All were convinced that the Tibetan people were ready to convert en masse to the Christian faith.

The Second Journey

In June 1625, Andrade and four colleagues departed on the second journey to Tibet. When they reached Zaburang, the missionaries were given a house to live in next door to the king's son, and the king "declared his resolution of having himself instructed in all of the principal points of the Christian religion, and only desired to wait till we should have acquired the language of Tibet."

Andrade and his co-workers made good progress, and soon they were sharing their faith in Tibetan. Andrade wrote that when he preached on the torments of hell, "The king looked very sorrowful and the queen wept silently. Among the 20 courtiers present, some said that it was a blessing God had caused us to be born so that we would teach them."

The king of Guge personally laid the cornerstone of the first church building of any description in Tibet, having paid all the construction costs.

The prince appears to have been the first member of the royal family to declare his new faith openly, while King Chadakpo

"was a frequent visitor to the house where the missionaries lived.... The king never tired of asking questions about Christianity and said that when he was catechized sufficiently, he would become a Christian...and would not need to fear because God would be with him."

The queen's mother, meanwhile, also showed a keen interest in the gospel. Every day she attended the church services, listening from the veranda. Later, when the king suggested that a new residence be built for the missionaries, part of the queen mother's home was moved to accommodate the change. Andrade expressed concern for the queen's feelings over this, but she indicated that "she would be willing to give up her whole house and be on the street for them.... Their houses were well built and the best in Zaburang except for those of the king."

King Chadakpo spared no expense in helping the missionaries to spread their message. When he learned that most churches are adorned with a cross, he arranged for wood to be brought from another country, due to the scarcity of trees in the Guge region. The king decided to completely cover the cross with brass, and he erected it at the highest point of the city, so that it could be seen from all directions when the sun reflected off it. A second cross was placed over the church and could also be seen from a distance.

The royal family attended the Christmas services that year, and agreed to fast, which moved the missionaries greatly. Andrade reported that when the nativity scene was revealed at midnight, "the people shed many tears and showed great reverence to the Christ Child, prostrating themselves many times on the ground. The king returned the next day and joined the queen for several hours in front of the nativity scene."

Rising Tensions

Andrade and the other missionaries were thankful for the liberty they had been granted and were confident that "Christianity would spread in Tibet much faster than in any other eastern mission. Andrade said he did not know of any other mission that had accomplished what the Tibet mission had in such a short time."

Several months passed, and while the king was happy for the queen and prince to be baptized along with any of his subjects who believed in Jesus Christ, he warned the missionaries that if he was converted it would bring a severe backlash from the Buddhist leaders. A riot had nearly ensued after the prince had appeared wearing Portuguese clothing, and the king knew that he risked being overthrown if he openly embraced the foreigners' religion. The threat of revolution appears to have dampened King Chadakpo's enthusiasm, and there is no record of him being baptized.

At the time, the king's brother was also the chief abbot of the large Tholing Monastery, situated 12 miles (19 km) from Zaburang. An emergency meeting was called by the monastery leaders, at which both the king's brother and uncle were charged, in the name of Buddha, to use all their influence to steer the king away from Christianity.

A short time later, King Chadakpo issued an edict in a bid to diminish the power of the monks, most of whom were forced to abandon their clerical robes and lead secular lives. The number of monks at Tholing dropped from 5,000 to less than 100. The battle lines had been drawn, and a serious confrontation loomed as the Buddhist hierarchy fought for their survival.

Hope Extinguished

When the king of Ladakh—310 miles (500 km) to the south—was informed of the discontent among the Guge lamas because of the king's embrace of Christianity, he immediately seized on the opportunity and dispatched a massive army across the Himalayas in the summer of 1630.

King Chadakpo was bound with chains and exiled to a dungeon in Ladakh, while according to Tibetan accounts the other royals were beheaded, and the women of the city were thrown over the edge of the citadel to their deaths hundreds of feet below. Their brightly-colored dresses made them look like flowers falling to the earth, causing the Ladakhi soldiers to shout for "more flowers" as the Guge kingdom was completely destroyed. Amazingly, nearly 400 years later, piles of decapitated skeletons were discovered at Zaburang, still stacked up in the place they were killed in 1630.

When more missionaries arrived in Zaburang in August 1631 they found that the new king was not as friendly as King Chadakpo had been. The new ruler had oppressed the Tibetan Christians, and most had been forced into exile. Before the war, Zaburang had boasted a population of about 10,000, but the city had been so devastated that it now contained only about 500 people.

Andrade applied to return to Tibet, but was rebuffed by his Jesuit superiors. The Portuguese missionary suddenly died in Goa in 1634, while still trying to return to Tibet. He was just 53-years-old. Some accounts say he was poisoned by an enemy, while others accuse the Muslims of murder. Although he died in India, Andrade's heart and soul were with the Tibetan people whom he loved so dearly.

The Jesuits attempted to re-establish the work in Guge in 1635. Seven workers were dispatched to Tibet, but three fell sick on the way and two more died from the demands of the journey. Just two made it there alive.

By 1642, only Manuel Marques remained in Zaburang. He reported that he had been attacked and injured, and a final pitiful letter from him was received at the Jesuit headquarters at Agra, in which he begged for rescue. From that point on, "the records fall silent. It is believed that he later died in prison."

A Christian remnant remained in the Zaburang region until the work was finally abandoned in 1650. The surviving Tibetan Christians—believed to number about 400 at the time—were singled out for retribution. They were sold into slavery, and the church building and the missionaries' homes were demolished. By then the kingdom of Guge had collapsed, and all traces that the gospel had ever been there soon vanished.

The Legacy of the Guge Mission

The extraordinary advance into Tibet by Antonio de Andrade and his colleagues had promised much and appeared to be on the cusp of a great breakthrough, but ultimately it delivered little as the missionaries had relied totally on the favor of the king. Once the king was overthrown, their work was quickly dismantled.

Before the Guge mission was abandoned, the Jesuits had set their sights on central Tibet. Four men left their base in Bhutan and made it as far as Xigaze in 1626, but they were turned back by the Tibetan authorities. The missionaries had more success in Bhutan, however, where, "with the permission of the king and queen, they built a church and baptized 12 people, including the queen's niece, who was a daughter of the king at Lhasa."

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book ‘Tibet: The Roof of the World’. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. Tsering, Sharing Christ in the Tibetan Buddhist World, p. 75.

2. L'Abbé Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2 (London: Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts, 1857), p. 251.

3. C. Wessels, Early Jesuit Travelers in Central Asia, 1603-1721 (The Hague, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff, 1924), p. 54.

4. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2, pp. 257-58.

5. Some scholars believe the name of the king of Guge was Thi Tashi Dagpa. Andrade never mentioned the king's name in his letters.

6. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2, p. 261.

7. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2, p. 264.

8. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2, p. 265.

9. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2, p. 266.

10. Joseph C. Abdo, The Christian Discovery of Tibet: The Origins to the Jesuit Mission at Tsaparang (Lisboa, Portugal: Tenth Island Editions, 2011), pp. 103-104.

11. Abdo, The Christian Discovery of Tibet, pp. 108-109.

12. Abdo, The Christian Discovery of Tibet, p. 115.

13. Abdo, The Christian Discovery of Tibet, p. 121.

14. In 2006, a superb documentary, "Guge: The Lost Kingdom of Tibet," was produced. It gives an excellent overview of the rise and fall of the Guge kingdom, and touches on the influence Andrade and the Jesuits made. The video is available on Youtube.

15. Lambert, "The Lost Kingdom of Guge," China Insight (July-August 2000).

16. Andrade's journals were rediscovered in Calcutta in the 19th century. They captured the imagination of author James Hilton, whose novels depicting Shangri-La owed much to the Portuguese missionary's accounts from 300 years earlier.