Annie Taylor

A 'most troublesome child'

Of all the heroic stories of missionaries who spread the gospel of Jesus Christ in Tibet, few are as intense and compelling as that of Annie Taylor, a single woman whose rugged individualism and boundless determination resulted in her being the first recorded Western woman to set foot in central Tibet.

Born in Cheshire in 1855, Annie was the daughter of a wealthy English businessman. She later described herself as "a most troublesome child, and very full of mischief." After being diagnosed with a heart valve disease at the age of seven, Annie nearly died two years later from an attack of acute bronchitis. The doctors were sure she would not live to see her teenage years, so her parents left her alone to do as she liked.

After she converted to Christ at the age of 13, the Holy Spirit deeply touched Taylor and she desired to give herself to missionary service, much to the dismay of her well-to-do parents, who were proud of their high positions in British society. They threatened to cut Annie out of their will, but she was determined to follow God. When Annie was 28-years-old:

"Her father required her to renounce Christian work, but she steadily refused. Finally he gave an ironical consent to her missionary plans, of which she availed herself immediately by entering one of the London hospitals for an elementary medical course. The consent was immediately withdrawn, and there was soon an open rupture at home. Allowances ceased. She sold her jewels, and with the proceeds paid her way at the hospital, while supporting herself in cheap lodgings, till reconciliation took place."

Annie forged ahead and applied to join the CIM. She sailed to China in 1884, and was appointed to the town of Taozhou (now Luqu in Gansu Province) on the border of Tibet.

The new recruit soon proved to be a handful to her missionary colleagues, who found her personality abrasive and rude. Hudson Taylor realized he had a potentially explosive problem on his hands. In 1890 he wrote of "dear Annie Taylor having a very hard time of it," and described her as "an individualist so bad at harmonious relationships with colleagues that she would have to be returned to Britain or stretched to her own limits."

Faced with a choice of going home in disgrace or continuing as an independent missionary without the support and encouragement of a team, Annie chose the latter option. First, however, her health had taken a turn for the worse, and she traveled to Australia for a time of recuperation.

Thinking they had seen the last of her, the members of the missionary community were surprised when Annie Taylor took advantage of her father's wealth to relocate to the southern side of the Himalayas. She established herself at Darjeeling, India, close to the Tibetan border. She often traveled north into Sikkim, where she gazed wistfully at the perennially snow-capped peaks, beyond which lay central Tibet, and the forbidden city of Lhasa, just 220 miles (356 km) to the north.

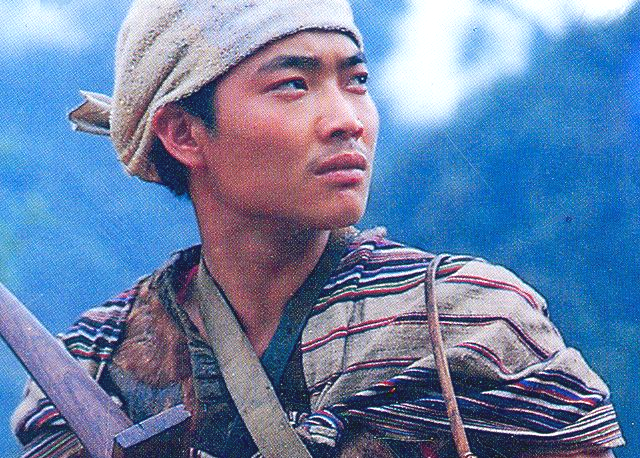

While studying Tibetan, Annie led a 19-year-old Tibetan boy named Pontso to faith in Christ, after he received medical treatment from the missionary. Pontso had "never seen a foreigner before, but the kindness and care with which Miss Taylor nursed him in his sufferings completely won his heart. He became a believer and...devoted himself to the service of his benefactress, justifying the trust she had placed in him by his unfailing courage and fidelity."

Annie's time in Darjeeling was far from easy. When the Tibetans learned of her intentions to evangelize Tibet, curses were placed on her, and many locals did all they could to dissuade her from her plans. When none of that worked, she was invited to dinner by a Tibetan chief's wife. Thinking it was a wonderful opportunity to establish a new relationship, Taylor went along and was fed an appetizing meal of rice and eggs. Almost as soon as she had swallowed the first mouthful, "she fell seriously ill, with all the symptoms of aconite poisoning. On her recovery she wisely left this district, and settled down to live a life like the natives in a little hut near the Tibetan monastery of Podang Gompa."

The First Western Woman in Tibet

A deep-seated desire to be the first Evangelical Christian to set foot in Lhasa spurred Annie on, but realizing the border between India and Tibet was firmly locked, she launched an ambitious plan to reach Lhasa via the Amdo region in northern Tibet.

In September 1892, with the harsh winter months approaching, Annie decided it was time to leave on the 1,000 mile (1,620 km) journey to Lhasa. Taylor—accompanied by her faithful helper Pontso, a Chinese Muslim and his Tibetan wife, and two other men— set out with 16 pack horses carrying food and equipment.

The expedition soon ran into trouble. Annie's Muslim guide twice attempted to murder her so he could steal the provisions and animals, and only the attentiveness of Pontso spared her life. As they passed through the territory of the wild Golog Tibetans, some of their horses and equipment were stolen.

Taylor had adopted typical Tibetan dress and shaved her head in a bid to disguise herself as a Tibetan nun. She refused to give up, and they soldiered on. She slept out in the open air, trusting God to protect her from both murderous men and the many wolves and wild beasts that roamed the area.

Each day the journey became more chaotic, with one source saying: "Bandits stole their tent and clothing and killed most of their animals. One of the workmen died, and another turned back. The Chinese man demanded money, and when she refused, he brought accusations against her to the Tibetan authorities that led to her arrest."

After interrogating her, the Tibetan officials wrongly assumed that Annie would realize the futility of her plans and return to China. She would not be stopped, however, and continued to press on into central Tibet, where she reported traveling for two months without seeing a single dwelling. During that time she was unable to change her clothes, but stumbled on in a state of exhaustion, refusing to give up.

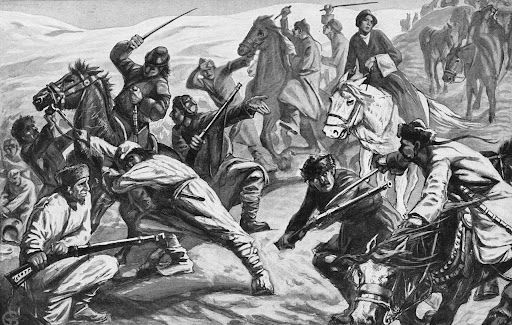

From time to time the travelers came across settlements of nomads, but this was no blessing, as the bloodthirsty men had never seen a white woman before, and they often looted and killed strangers who were foolish enough to venture into their territory. In one place, a large group of bandits surrounded Annie and her tiny group, threatening to kill them. They launched a sudden attack, which Annie later described:

"A force of 200 bandits surrounded our feeble party, and the whistling bullets spattered the stones with blood. They were traveling with a company of Mongols and laden yaks. The beasts stampeded; several of them were shot, and with them fell two men, face downwards, whose muffled bodies were left lying still and cold for the oncoming night to cover and the pitiless rain to pelt."

Finally, after months of agonizing travel, Annie Taylor, Pontso and a Tibetan helper named Sigju were just three days from Lhasa! Every trail into the city was tightly guarded, however, with the Dalai Lama's soldiers instructed, under penalty of death, to stop all travelers attempting to reach the golden city. Permission had to be granted before anyone, even Tibetans, could proceed.

The Tibetan soldiers were shocked to discover that the three travelers were led by a single Englishwoman whose provisions had run out. The officials ordered her to turn back to China, but she strongly argued that if they went back they would surely die, and their blood would be on the officials' hands.

A huge white tent was erected so that the Tibetan officials could discuss what to do with their prisoners. Investigations were conducted, and a report was dispatched to the Potala Palace for the Dalai Lama to read. Annie knew that the trial would determine the fate of her life. For 15 long days,

"Taylor stood at bay, fighting for her life and the lives of the two Tibetans.... They knew their fate hung on the judgment of those tea-drinking chiefs.... In the center sat the woman on whose account all this fuss was being made—a foreigner, and therefore guilty of criminal trespass; a prisoner, unarmed, and absolutely without provisions."

When a letter from the Potala Palace arrived and Annie saw the grim countenances of the two officials, she knew there was no chance she would be allowed to enter Lhasa. Always one to press the boundaries, she began to argue vehemently that she be permitted to bypass the city and cross the border to India. When this proposal was also steadfastly rejected, "she wrung from the chiefs, as compensation for this refusal, a tent, horses, and provisions sufficient for the return to China."

Months passed as the audacious missionary and her two colleagues staggered toward Kangding in the Kham region, beyond the borders of central Tibet. One account said: "The cold was almost unspeakable, and the food they tried to cook over their dung fires was often eaten half raw and little more than half warm.... For 20 days at a stretch they had to sleep on the ground in the open air, the snow falling around them all the while."

Annie and her two Tibetan friends finally reached Kangding in April 1893, seven months and ten days after they set out on their historic journey.

A Predictable Ending

Although Annie Taylor's brave attempt to reach Lhasa had failed, she had come closer than any other Evangelical Christian in history, and the gospel of Jesus Christ had been preached along the way.

When news of Taylor's trip trickled back to Europe and America it electrified people, and for a time she became a celebrity. Meetings were hastily organized, in both churches and secular institutions, where people gazed with admiration on the first Western woman to have visited Tibet.

Many Christians were deeply challenged, and Tibet became the subject of people's conversations and the focus of prayer meetings. Many men expressed shame that a single woman had displayed more daring and gone further into Tibet than any male missionary.

Buoyed by the attention, Annie established the Tibetan Pioneer Mission, and in a short space of time a group of 14 eager male missionaries traveled to India, hoping to enter Tibet through Sikkim.

Those who knew the region well, however, could see a disaster about to happen. Taylor herself had failed to enter Tibet through Sikkim on numerous occasions, and mission leaders were concerned that the name of the new mission would give the impression that for the first time Evangelical work was being conducted in central Tibet. The new mission's first publication openly encouraged the false impression that the work was based inside Tibet, through a series of half-truths. The Tibet Pioneer Mission's statement said:

"The field of operations is the country of Tibet itself, as far as entrance can be obtained into it, rather than the border tribes, among whom work is already commenced. Tibet, which lies north of India and west of China, is a large country...and as yet we are the only Protestant missionaries (so far as known) within its borders."

Soon after arriving in north India, the men saw there was a wide gap between the reality of Annie Taylor's leadership and her character. Predictably, dissent soon broke out, and within a few months the ill-equipped recruits realized they were way out of their depth, and all but one resigned from the fledgling mission. They began to head home, confused and bewildered by the shambolic experience.

Annie would not be deterred, however. Although her new mission was about to be dissolved, she wrote to churches in Britain, asking them to send female workers, because "the Tibetans respect women and do not even in time of war attack them."

She remained in Sikkim, accompanied by her faithful servant Pontso and a few women who had responded to the call to join her. They continued to share the gospel with many Tibetans who crossed the border, and large quantities of gospel literature were taken back into Tibet and spread far and wide. Letters from some of the missionaries on the border provide insight into the effectiveness of this literature ministry. In 1895 Taylor reported:

"Every evening there are from four to 14 fresh encampments, with an average of six Tibetans to each camp. I go out and bid them welcome, and they invite me to sit with them around the fires, which I do; and then after giving each of them a Scripture card, I tell them the old, old story of Jesus and His love for poor lost sinners.

They generally listen most attentively, and as they come from all parts of Tibet with the wool, the message is carried far and wide into Tibet. I have given nearly 3,000 cards, and they are much appreciated. But the more thoughtful of them want something more. One man, a lama, said to me when I gave him a card, 'Can you not give me a book?' So I gave him a copy of one of the Gospels. I have been able to give away over 500 Gospels in Tibetan, which I hear are being read by the lamas in various monasteries, even in Lhasa."

Annie Taylor, the unique and abrasive pioneer missionary who doctors said would not reach her teenage years, finally returned to London in 1904, and passed away in 1922 at the age of 67.

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book ‘Tibet: The Roof of the World’. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. Annie R. Taylor, Pioneering in Tibet (London: Morgan & Scott, 1895), p. v.

2. William Carey, Travel and Adventures in Tibet including the Diary of Miss Annie R. Taylor's Remarkable Journey (New Delhi, India: Naurang Rai for Mittal Publications, 2002), p. 148.

3. Ruth A. Tucker, "Unbecoming Ladies," Christianity Today (Fall 1996).

4. John C. Lambert, Missionary Heroes in Asia (London: Seeley, Service & Co., 1925), p. 122.

5. Lambert, Missionary Heroes in Asia, p. 121.

6. Tucker, "Unbecoming Ladies," Christianity Today (Fall 1996).

7. Carey, Travel and Adventures in Tibet, pp. 140-41.

8. Carey, Travel and Adventures in Tibet, p. 141.

9. Carey, Travel and Adventures in Tibet, p. 142.

10. Lambert, Missionary Heroes in Asia, pp. 132-33.

11. Taylor, Pioneering in Tibet, p. 76. At the time, Annie Taylor was based in the Chumbi Valley, which was under the jurisdiction of British-controlled India. Today, however, the valley is disputed, with both India and China claiming ownership.

12. Tucker, "Unbecoming Ladies," Christianity Today (Fall 1996).

13. Taylor, Pioneering in Tibet, pp. 52-53.