Albert Shelton

Prince of Tibetan Missionaries

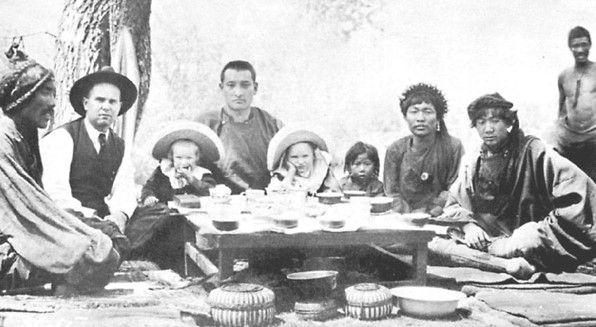

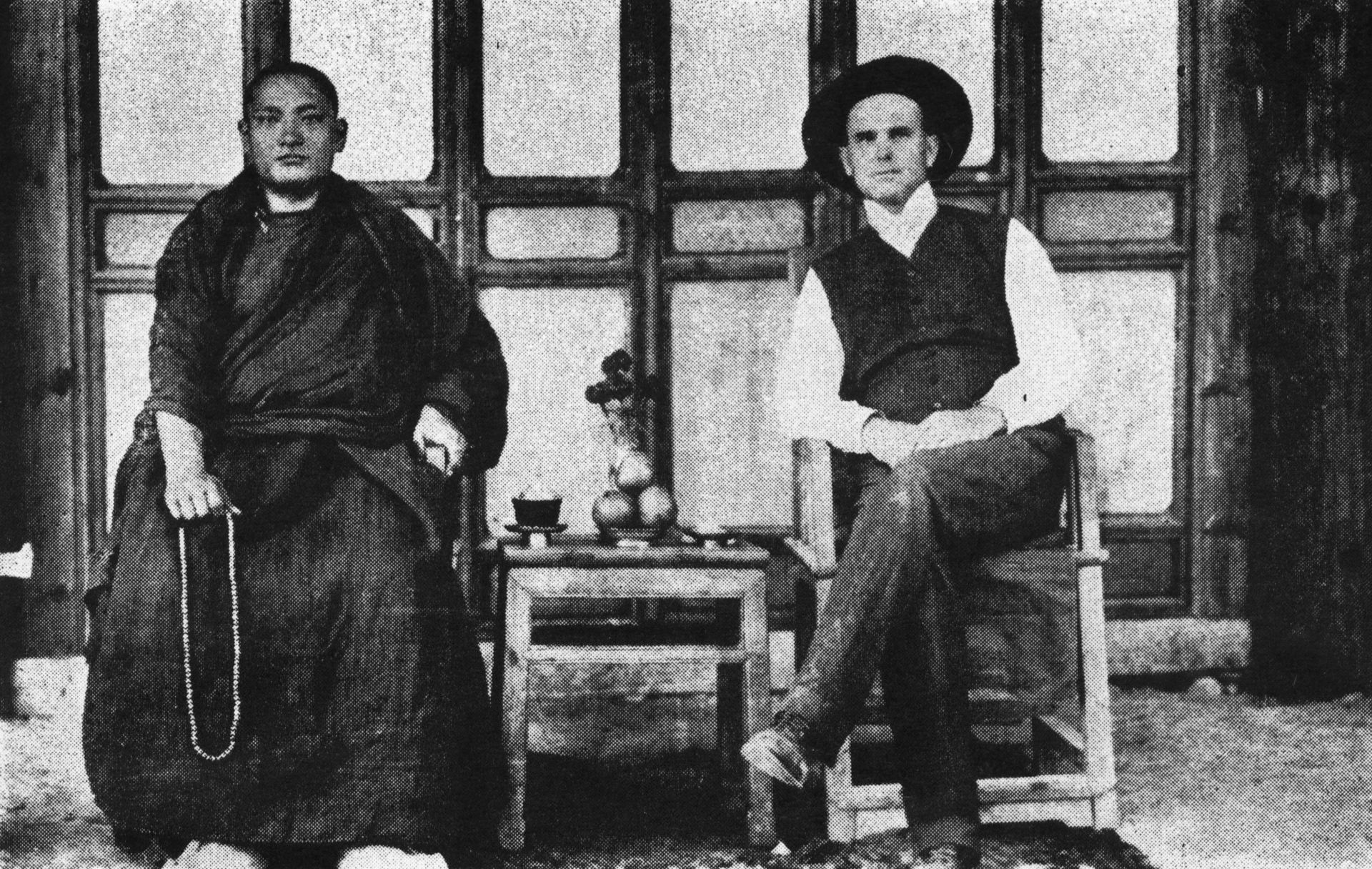

Born in Indianapolis in 1875, Albert Shelton was a member of the Disciples for Christ in America and a medical doctor. At the height of his ministry, Shelton was so respected in Evangelical circles that he was dubbed the 'Prince of Tibetan Missionaries,' even though he never learned to read or write the Tibetan or Chinese scripts.

In March 1904, shortly after arriving in the remote town of Kangding on the border between Tibet and China, Shelton and his wife Flora were shocked by the reality of life in a war zone where fierce conflict could erupt at any moment. Their new home was described as

"a wild and dangerous place where brigandage and battle were inextricably woven into a unique culture of warriors and monks. Decapitated heads ornamented the trees and gateposts. Severed hands festooned the government buildings. The Chinese and Tibetans skinned men alive, chopped them into chunks, and boiled them to death in giant cauldrons."

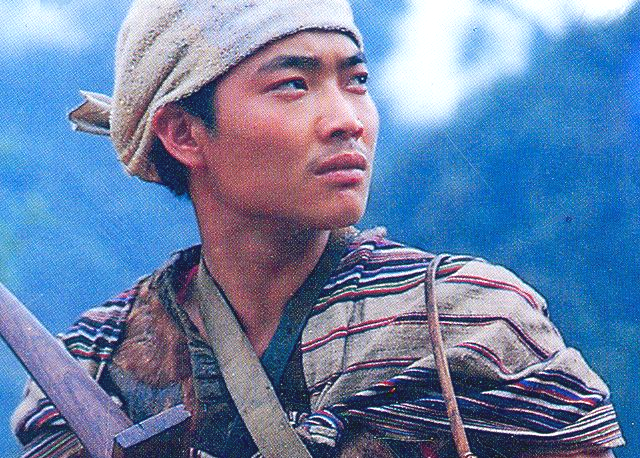

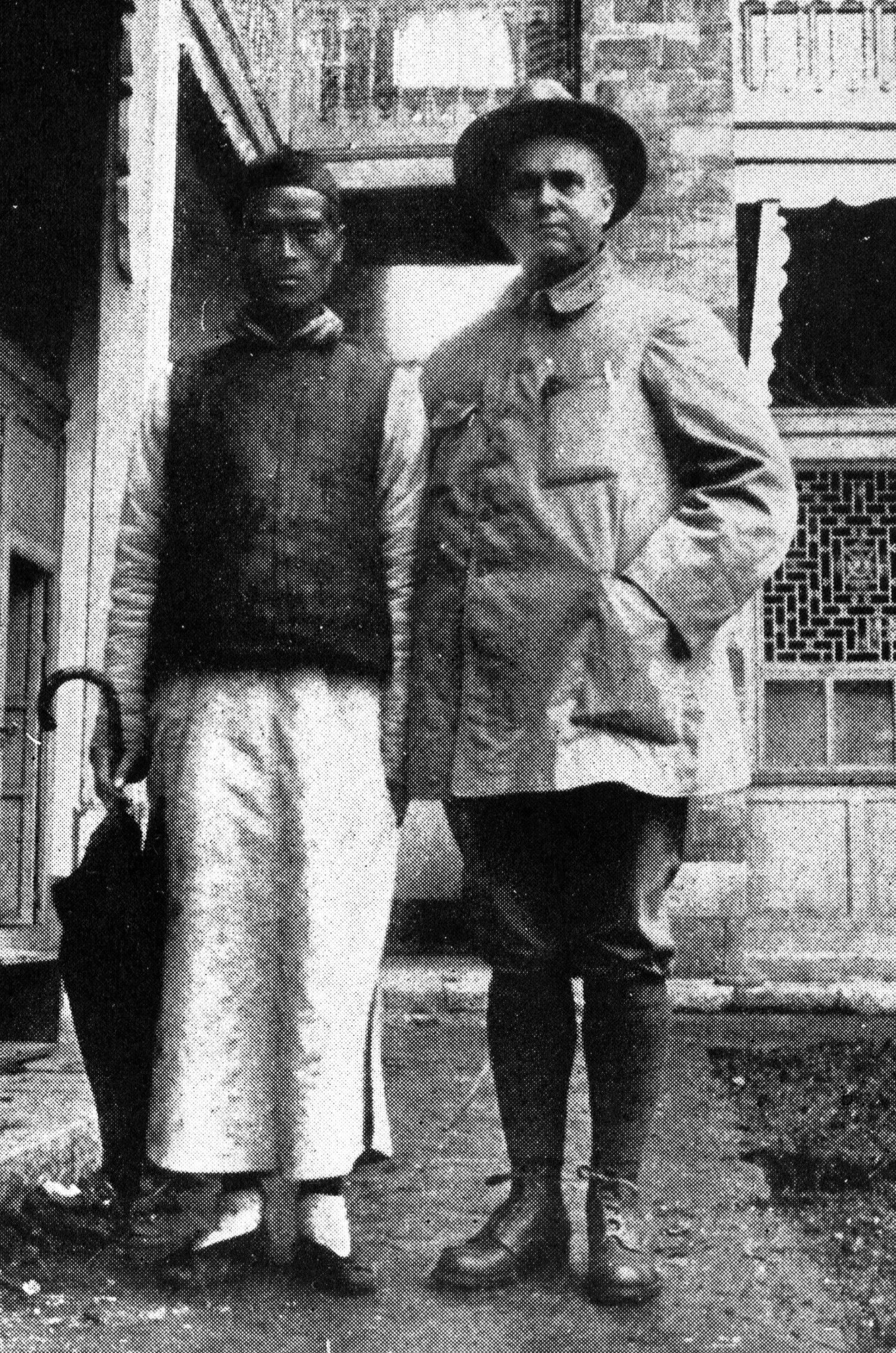

Soon after arriving on the mission field, Albert and Flora adopted a destitute half-Chinese, half-Tibetan orphan boy named Li Guiguang, whom they found living on a street near their home. They raised him with love and care, treating him the same as their two biological daughters.

A Full-Service Ministry

After several years in Kangding, the Sheltons and another missionary family, the Ogdens, moved 17 days further west to set up the first ever Evangelical mission in the extremely remote town of Batang, which at the time was home to 350 Tibetan families. They threw themselves into their work, adopting a "full service ministry" to reach the Tibetans by any means possible. A summary of their work said:

"They ran a kindergarten, as well as a school for older students. A hospital was erected, and from this base Dr. Shelton and other doctors did mobile clinic work in the surrounding area. A church was quickly formed, and Sunday classes for both Chinese and Tibetan children were commenced. One missionary led the Chinese class on one side of the room, and Dr. Shelton led a Tibetan class on the other side.

The wives did visitation in many country homes, seeking to win the women and children. Missionaries engaged in efforts to help the poor, the beggars, and destitute children to acquire a vocation from which they could make a living. To achieve this goal they taught people to weave rugs, to make soap, to make shoes, and how to farm and garden. Early results from these varied ministries were good."

The medical work often faced a shortage of supplies due to the remote location and inability of patients to pay for treatment. Albert and the other missionaries plunged all their personal resources into the work, often putting their own needs to the side in order to show the love of Christ to the people around them. Shelton's biographer remarked:

"By American standards, the medical fees Shelton received were laughable—about a nickel for everything from a sword wound to a leg amputation. One year Shelton's fees totaled a quantity of eggs, meat, yak butter, gunnysack cloth, a few wolf skins, and 96 rupees—less than $25.... One afternoon a band of frostbitten Chinese soldiers came to the dispensary. That day Shelton amputated 31 fingers and toes."

On one occasion a Tibetan leper knelt down before Shelton as a way to show his appreciation for the doctor's help. The missionary immediately took hold of the man's arm and lifted him to his feet, firmly saying, "Get up from there. We do not allow anyone to get down on their knees to us. Before God, one man is no more and no less than another, whether he is a beggar or leper or no matter who he is." His humble attitude helped Albert to be at ease with everyone he met—whether government officials, Buddhist lamas, or peasants.

Shelton soon realized that for the kingdom of God to take root among the people of Batang, help would need to be provided to alleviate their chronic poverty. The Batang countryside was extremely dry and desolate, but the missionaries came up with a plan to transform the area.

While continuing to share the message of eternal life, under Albert's leadership, the Americans dug an irrigation canal 5 miles (8 km) long, to bring water from the upper reaches of the Xiaoba River. The locals named it "Foreigner Channel" in the missionaries' honor. A total of 165 acres of land was transformed and became fertile, and the valley became a garden of Eden in a barren landscape. Apple, apricot and peach orchards sprang up throughout the area, adding much needed variety to people's diets and generating income that lifted the grateful people out of poverty.

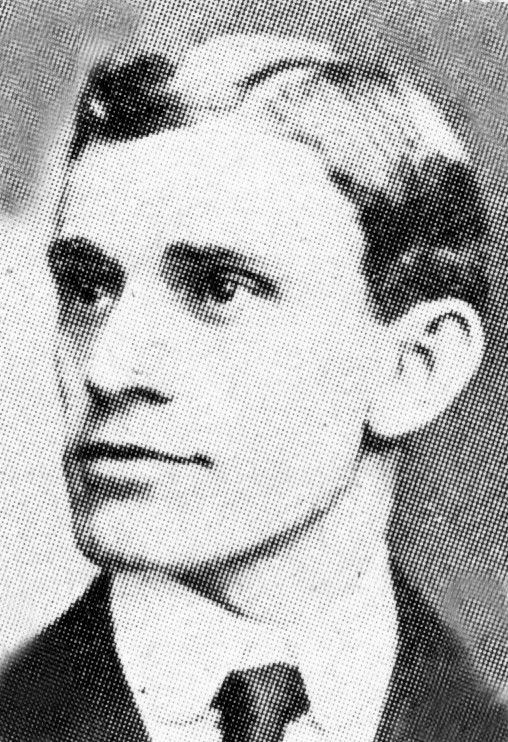

Zenas Loftis

Although the list of Catholics who had died in the Kham region had grown to a considerable length, the Evangelicals suffered a blow when 28-year-old Zenas Loftis, from Gainesboro, Tennessee, died just a few months after arriving at Batang in 1909. For years Shelton had been asking God to send a missionary-doctor to join the work, and he was overjoyed when Loftis volunteered to join them.

After graduating as a medical doctor from Vanderbilt University, Loftis had started a career in the pharmaceutical business, before the love of Christ compelled him to give up the comforts of his homeland and spend his life for the Tibetan people.

After reaching Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province, the young recruit spent more than two weeks on horseback as he made his way west. En route, Loftis visited the grave of the China Inland Mission's William Souder, who had died of illness in 1897 at a remote place two days from Batang. Souder's humble gravestone carried a powerful message: "I would like to have lived a little longer, but Thy will be done; only send another to take my place. Take up the torch and wave it wide: the torch that lights life's thickest gloom."

That night, Loftis was unable to sleep. He felt as though the Lord was asking if he too was willing to suffer death as a martyr in this forgotten land. The young missionary arose in the middle of the night and wrote in his diary: "Sleep on, thou servant of the Living God. If it be Thy will that I, too, should find a grave in this dark land, may it be one that will be a landmark and an inspiration to others, and may I go to it willingly if it is Thy will."

Loftis soon found his doctor's surgery in Batang overwhelmed with visitors when a smallpox epidemic broke out just weeks after his arrival. When patients began to die from typhus, he refused to leave the area, believing his call compelled him to remain at his post and treat the sick regardless of the risks. Despite vaccinating himself, Loftis caught both smallpox and typhus, and died six weeks later on August 12, 1909.

The other Batang missionaries were shocked that the young doctor for whom they had prayed so long was so quickly cut down. Shelton described the impact that Zenas Loftis' short ministry had on the mission:

"We in Batang were stupefied and asked the eternal question, 'Why, why?' And in an endeavor to find the answer to this question, we got closer to the Lord than we had ever been. In so doing, the Spirit of the Lord was enabled to work and use us as He had never been able to do before. The school grew in numbers and in effectiveness, and a great many people that had never come near the church before began coming."

When Loftis' death was announced in his home church, a young Christian doctor named William Hardy immediately offered to take the place of his fallen brother. Hardy was joined by other missionaries, and the Evangelical work among Tibetans in Batang grew rapidly, and over time a number of solid converts were won to the faith.

Fruit After Many Days

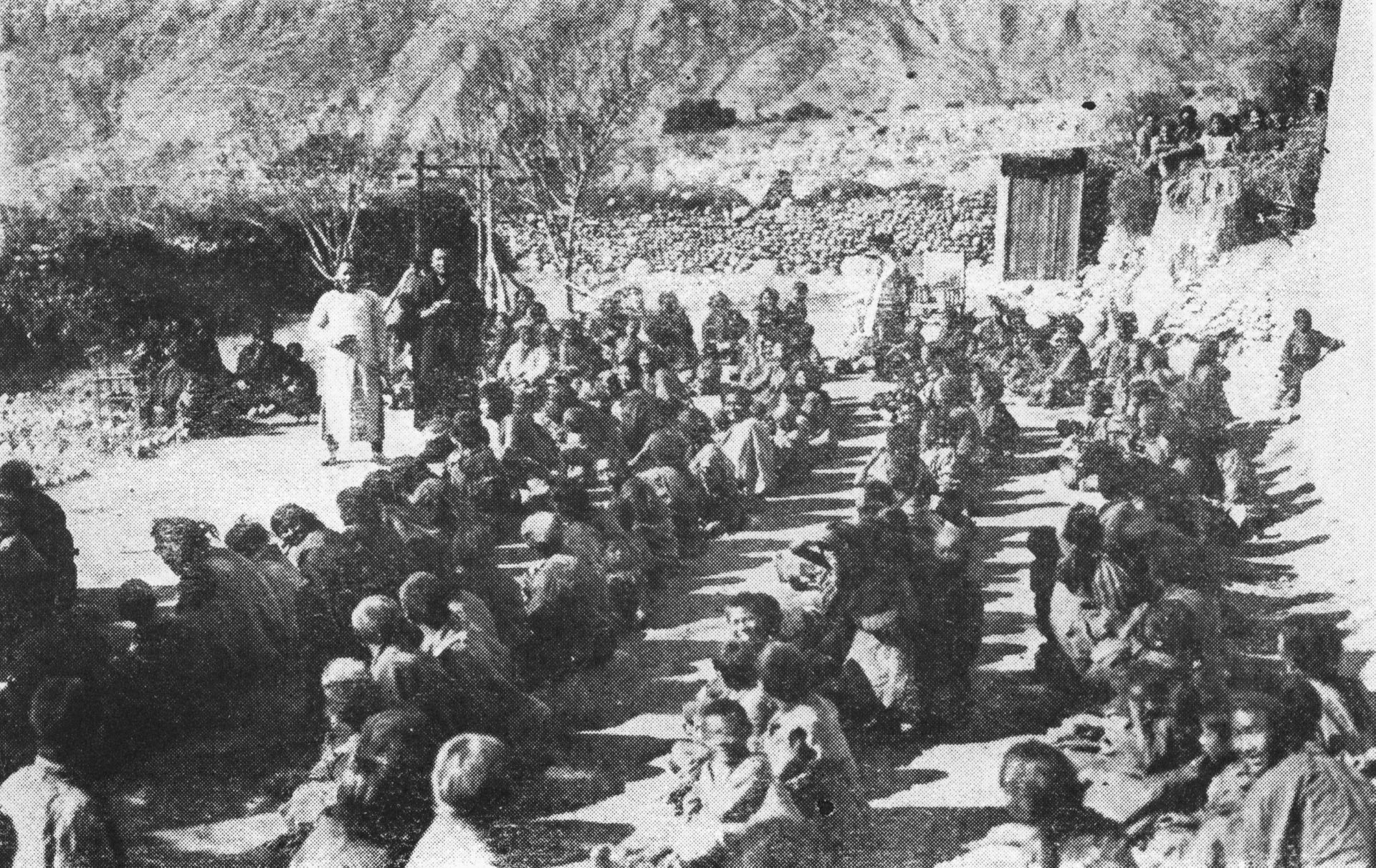

When a revival broke out in many parts of China in 1911, its influence spread all the way to Batang. The results were overwhelming, with one report saying that more than 200 (mostly Han Chinese) people at Batang had

"confessed their sins of robbery and murder, were trying to quit opium and wine-drinking, and had asked the missionaries to go into their homes and tear down idols, which they gladly did, leaving in their places the Lord's Prayer. Church services were always crowded, but as with every other group and its audience and converts, Chinese usually outnumbered the Tibetans."

Missionary James Ogden excitedly wrote about the amazing growth that occurred in the Batang church after the visitation of the Holy Spirit: "Today at our regular service the house was jammed full of Chinese, Tibetan women, and children. There was hardly room to breathe, but the talk was listened to with deathly silence. Certainly we are getting a chance to sow some seed. May it spring up and grow!"

Shelton's long-term dream was to establish a hospital in Lhasa, the capital and spiritual stronghold of the Tibetan world. For years he tried to send a message to the Dalai Lama, seeking permission to travel to Lhasa and set up a medical clinic there. The Dalai Lama finally responded: "I know of your work and that you have come a long way to do good. I will put no straw in your way." Before Shelton could start out for Lhasa, however, the political situation deteriorated and bloodthirsty bandits ruled the countryside.

The Shelton family returned to America on their first furlough in 1910, taking 89 days to travel from Batang to San Francisco. Realizing that the struggling economy in the United States was placing a great strain on his mission organization's budget, Shelton had collected numerous Tibetan works of art and antiquities, which he sold to the Newark Museum.[i]

Although the family's return to Batang was delayed until 1913 because of war and instability in the Kham region, when they finally reached their home, Shelton had sufficient finances to construct a large mission compound, which included a medical clinic and residence. For years the gospel went out to thousands of Tibetans in the surrounding areas, with Shelton riding hundreds of miles each year on the back of his trusted mule.

In 1920, while traveling with his wife and daughters, Shelton was kidnapped by bandits who demanded a $25,000 ransom for his release. The rest of his family, though badly shaken, were allowed to go free. Hauled off into the mountains, Shelton was held for 71 days. During the whole time he refused to cooperate with his captors' demands, telling them, "You can kill me or do whatever you wish but I will not be ransomed."

While being held, Shelton lovingly treated the bandits who were sick and wounded, and they gradually came to view the missionary as their friend. After more than ten weeks in captivity, Shelton's body was so emaciated that he was unable to stand up. In an act of compassion, the bandits "left him by the side of the road where they knew he would be found by the government troops who had been following them."

At the start of 1922, with his wife and daughters back in the United States, Shelton planned the long and dangerous journey to Lhasa, intending to take up the Dalai Lama's invitation. By now the American missionary was 47, and was worried that his time was running out. He told a friend, "A man's ability to ride a mule over 17,000 feet [5,181 meter] mountains declines rapidly after he is 50-years-old."

When the bandits who had kidnapped Shelton a year earlier heard of his intended journey, they devised plans to kidnap him again. This time their intention was to keep him as their doctor. In February 1922 he commenced the long journey to Lhasa with three Tibetan companions. On the 16th, the other missionaries at Batang were told that a group of 20 bandits had ambushed and shot Shelton at a pass just 6 miles (10 km) away. Russell Morse and William Hardy rushed to the pass and found Shelton unconscious. They gave him an injection of morphine and carried him back to Batang.

His colleagues did all they could to revive him, but at 12:45 in the morning of February 17, 1922, Albert Shelton passed into glory. The small mission community at Batang was grief-stricken, and one of their members wrote: "His death is a great blow, piercing the very heart of the mission. He was truly an outstanding evangelist, and a tireless physician and surgeon. But more than this, he was our encourager, our joy, our constant inspiration."

Due to difficulties in communication at the time, weeks passed before news of Shelton's murder made it to the outside world, and unfortunately Flora and the two girls first heard the news from the American media.

A funeral service was conducted by Li Guiguang, the orphan boy whom the Sheltons had adopted 18 years earlier. Li had matured into a fine Christian man and was an effective evangelist among both the Tibetans and Chinese living in the Batang region. After Shelton's death, churches in America established a memorial fund in his name, "raising over $100,000 for the purpose of founding new mission stations in the Tibetan territory that he had so loved and for which he gave his life."

As news spread about Shelton's life and death, many young people volunteered to take his place on the mission field, including 28 from Enid, Oklahoma, alone. An historian summarized the stellar contribution Albert Shelton made to the work of God's kingdom among the Khampa Tibetans:

"Skilled as a surgeon, fluent in Tibetan, compassionate in his ministry to people, he ministered to both Chinese and Tibetans in many war situations and was respected equally by all, who recognized him as a man of God. Some of these contacts gave him hope that he might be able to establish a hospital in Lhasa. Before this became even remotely possible, he was gunned down by brigands."

Although they had lost their influential leader, the remaining missionaries in Batang bravely soldiered on, and by December 1925 it was reported:

"Attendance at the Tibetan Sunday school averaged around 170, with the lowest at 148 and the highest at 188.... The day before Christmas, 647 of the poor people of Batang were given a good dinner and a Gospel sermon by our chief evangelist.... The story of Jesus was retold by Li Guiguang. He also gave a good dramatization of The Prodigal Son to the audience of 600 or 700 people."

Despite these encouraging signs, the other Batang missionaries struggled to move forward after Shelton's death, and constant conflict between the Tibetans and Chinese resulted in the mission hospital and other dwellings being reduced to rubble. Finally, internal friction among the missionaries caused the mission to close in 1932, after 28 years of evangelism on the Tibetan frontier. The Batang church had dwindled to just 16 believers.

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book ‘Tibet: The Roof of the World’. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. MDouglas A. Wissing, Pioneer in Tibet: The Life and Perils of Dr. Albert Shelton (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), pp. 1-2.

2. Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China, pp. 74-75.

3. Wissing, Pioneer in Tibet, p. 74.

4. Flora Beal Shelton, Shelton of Tibet (New York: George H. Doran, 1923), p. 165.

5. Cecil Polhill, "The Tibetan Border," China's Millions (December 1908), p. 198.

6. Hefley, By Their Blood, p. 146.

7. A little-known book containing Loftis' diary entries was published two years after his death. See Zenas Sanford Loftis, A Message from Batang: The Diary of Z. 8. Loftis, M. D., Missionary to Tibetans (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1911). Albert L. Shelton, Pioneering in Tibet: A Personal Record of Life and Experience in Mission Fields (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1927), p. 77.

9. Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China, p. 75.

10. Flora Beal Shelton, Sunshine and Shadow on the Tibetan Border (Cincinnati, OH: Foreign Christian Missionary Society, 1912), p. 123.

11. Hefley, By Their Blood, p. 147.

12. Shelton's artefacts are still on display at the museum today. The wisdom of a missionary selling many of these items should be questioned, as for decades they have helped attract people to Tibetan Buddhism.

13. Gertrude Morse, The Dogs May Bark, But the Caravan Moves On (Chiang Mai, Thailand: North Burma Christian Mission, 1998), p. 27.

14. Morse, The Dogs May Bark, p. 27.

15. Wissing, Pioneer in Tibet, p. 179.

16. Morse, The Dogs May Bark, p. 50.

17. Morse, The Dogs May Bark, p. 59.

18. Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China, pp. 72-73.

19. Morse, The Dogs May Bark, p. 91.