1880s

The First Evangelicals

For approximately 600 years the Roman Catholics were the only representatives of Christ in Tibet. This finally changed in 1877, with the arrival of the first Evangelical missionaries. Earlier that year, the magazine China's Millions, published by Hudson Taylor's China Inland Mission (CIM), had prepared readers for news that some members of the organization were about to penetrate the closed land of Tibet:

"Tibet has been, and still is, left undisputed in the hands of the destroyer, so far as Protestant Christians are concerned. Shall it continue so? ... We are thankful to say that two of our number are looking forward to Chinese Tibet as their future sphere of labor. But not without our prayers will the long-closed walls of Jericho fall down."

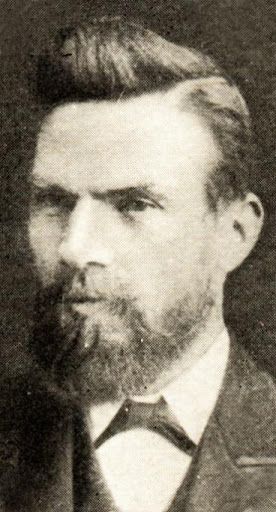

The honor of being the first Evangelical in Tibet belongs to James Cameron, a shipbuilder from the town of Jarrow in northeast England. After quickly becoming proficient in the Chinese language, Cameron relocated to Sichuan Province, where he joined George Nicoll, until a riot caused the duo to flee the town in March 1877. Cameron, Nicoll, and an American Presbyterian named Charles Leaman traveled toward Chengdu. Nicoll and Leaman fell ill from exhaustion, but Cameron refused to turn back, and set his sights on entering eastern Tibet.

Cameron traveled mostly on foot, only riding his mule for short distances. He sold Christian literature as he went, and kept a journal of his travels, filled with detailed observations of people and places. When he reached Litang in the Kham region, Cameron asked, "When shall 'Christ and Him crucified' be preached to the multitudes who speak Tibetan?"

Cameron continued to Batang, which for centuries had been considered the gateway to central Tibet. He crossed a pass 16,570 feet (5,050 meters) above sea-level, which left him out of breath. As he sank into deep snow, the Englishman's shoes fell apart, but he pressed on.

Having finally reached Batang after weeks of grueling travel, Cameron was turned away by innkeepers. Faced with the choice of heading further west into sparsely populated areas of central Tibet, or turning south toward Yunnan Province, Cameron chose the latter option, as "ignorant of the language, and therefore unable to preach to the people or to make the best of the situation, any such attempt would have been as useless as dangerous." He was also keen to get a sense of how far Tibetan influence stretched to the south.

When he reached the Tibetan town of Deqen in northern Yunnan, Cameron fell seriously ill with a high fever, and for weeks he was close to death. Believing it was better to keep moving, he mounted his mule and continued his journey. The further south he went, the more he was able to communicate in Chinese, and he preached in teashops along the way. He finally exited China into Burma (now Myanmar), and made his way back to south China by sea.

The Evangelical world rejoiced to hear that one of its number had finally set foot in Tibet. His journey was seen as a great breakthrough, and many others were encouraged to follow in his footsteps.

In August 1882, after seven years of doing little else but traveling in unexplored parts of China, James Cameron left for England for a much-needed break. During his extensive travels he had failed to visit just one Chinese province—Hunan. Amazed by his tenacity, people began calling Cameron the 'David Livingstone of China'.

Although he was just 38-years-old, Cameron was exhausted from his journeys, and in 1883 he moved to New York to study medicine. After earning his degree, he returned to China where he died from cholera in 1892, having lived his 47 years to the full.

Kham ཁམས་

The 1880s saw the first Evangelical missionaries arriving to reside in Kham areas, following James Cameron's visit in 1877. Many of the early pioneers were surprised to discover how deeply the Catholics had already put down roots in the region. They had established churches and schools in most of the main towns, and many of their priests had already laid down their lives on Tibetan soil.

Jean-Baptiste Brieux was one of several French missionaries murdered in the Kham region in the 1880s. The leader of the mission, Alexandre Biet, investigated the incident and concluded:

"The murder is not a simple act of banditry. The plot was woven in advance and I do not hesitate to believe that our dear brother poured out his blood for his faith, and that his assassins were paid by the Tibetan lamas. They committed this mortal sin not because we are foreigners, but because we preach a religion that is not Buddhism....

The assassins were only instruments of the real culprits: the lamas and monks of the Batang monastery.... The death of Brieux is a terrible blow for our poor Mission, so frequently and harshly tested. I relied much on this excellent missionary.... This apostle has sprinkled the ground of Batang with his blood. May this invaluable sacrifice advance the hour of God's merciful visitation, when Tibet opens its arms to us and the gospel!"

The murder of Brieux and the subsequent Chinese retribution added to the problems in Kham. The first resident Evangelical missionaries arrived in the area in the middle of this conflict, and had to quickly learn how to live and minister amid the tension.

Although many people think of Tibetans as respectful of all life, especially human life, murder was commonplace in Tibet, with violent men regularly plundering, raping and killing the innocent. One 19th century visitor was appalled to discover the cheapness of life on the Tibetan Plateau:

"In Tibet nearly every crime is punished by the imposition of a fine, and murder is by no means an expensive luxury. The fine varies according to the social standing of the victim....80 bricks for a person of the middle class, 40 bricks for a woman, and so on down to two or three for a pauper or a wandering foreigner. There is hardly a grown-up man in the country who has not had a murder or two to his credit."

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book ‘Tibet: The Roof of the World’. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. China's Millions (January 1877), p. 5.

2. A. J. Broomhall, Hudson Taylor & China's Open Century: Book Six – Assault on the Nine (London: Overseas Missionary Fellowship, 1988), p. 148.

3. "Through Eastern Thibet," China's Millions (August 1879), p. 101.

4. My translation of the Jean-Baptiste Brieux Obituary in the Archives des Missions Etrangères de Paris, China Biographies and Obituaries, 1800-1899.

5. "What it Costs to Murder in Tibet," Chinese Recorder (August 1891), pp. 358-59.