© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1900 - The Soping Slaughter

June 29, 1900

Soping, Shanxi

Ten missionaries associated with the Swedish Holiness Union were holding their annual mission conference at the remote Soping station in the northernmost part of Shanxi, just inside the Great Wall that separated China from the vast Mongol steppes beyond. Two families from other mission organizations were also attending the meetings in Soping at the time of the slaughter. They were Oscar Forsberg, of the International Missionary Alliance Mission, along with his wife and child, and C. Blomberg, also accompanied by his wife and child.

By the time the missionaries arrived in Soping for their meetings the small town “was already seething with unrest. As the meetings commenced on June 24, Boxer agitators were saying that the missionaries had swept away approaching rain clouds with a yellow paper broom and that the foreigners were praying to their God that it might not rain.”[1]

A group of Chinese believers were viciously burned to death first. One account stated: “The Mission premises were looted by the mob and then set fire to. The servants, Christians, and others friendly to the foreigners were then thrown into the fire by the rioters and burned to death.”[2]

A mob converged on the house where the missionaries and a number of Chinese believers were meeting on June 29th. As the mob attempted to smash down the front door, the Christians rushed out the back door of the house and ran to the magistrate’s headquarters, where they pleaded for protection. The Boxers gave chase, but the magistrate refused to hand the missionaries over to them. Instead, he bound five of the men with leg irons to placate the Boxers, and promised that the missionaries would be sent to Beijing to be executed. This seemed to please the bloodthirsty mob and they slowly drifted away. Later that night, however,

“the mob came back with soldiers sympathetic to the Boxers. Sparing no one, they stoned to death all the missionaries and their children along with Chinese Christians who had sought refuge. They hung the heads of the missionaries on the city wall as a ghastly testimonial to the populace.”[3]

Another account says that early in the morning, “the child of Mr. and Mrs. Forsberg was, indeed, torn asunder by the violence of the mob. Carlsson and Persson managed to flee, but were pursued, overtaken, and killed.”[4]

A Chinese evangelist named Wang Lanbu managed to escape the slaughter when he fainted while being questioned. Wang later reported the grim circumstances of the slaughter of his family and other Christians:

“My mother, brother, sister, my little child, and an old lady named Wu were burned alive. Not only this…the cart was burned, the mule killed and thrown into the flames, also the dog and chickens in our yard. People were not tied, but were just thrown into the fire and driven back whenever they tried to get out. It was a slow and bitter death.”[5]

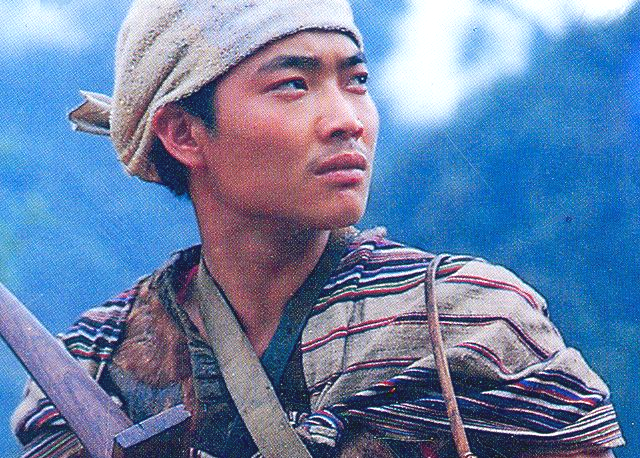

Nathanael Carleson.

The leader of the Swedish Holiness Union was 33-year-old Nathanael Carleson, who despite his youth, was the oldest of all the SHU missionaries. Growing up in the Swedish province of Nerike, Carleson received a call to serve as a missionary in 1890. He wrote, “The assurance that God wants me in China brings such an unspeakable joy to my heart.”[6] Carleson and his wife were deeply loved by the Chinese Christians, who often quoted a Bible verse when introducing him: “Here is a true Israelite, in whom there is nothing false.”[7] The Carlesons had two children. When they travelled home on furlough Mrs. Carleson and the children remained in Sweden while Nathanael returned to China alone. Three lives were thus spared from the Boxer cruelty, but a heartbroken family had to face life without their beloved husband and father.

Gustaf Karlberg.

Gustaf Edward Karlberg went to China in 1896. Before leaving Sweden he worked for the Lord on the island of Gotland. The Chinese took to his warm personality. It was said, “He was dearly loved and appreciated. He had the name of being tender-hearted, and was always able to show his sympathy to the Chinese in a marked way. He suffered a good deal from physical weakness, but endured.”[8]

Sven & Emma Persson.

Sven A. Persson went to China with Gustaf Karlberg in 1896. Beforehand they had spent three months in training with the China Inland Mission in London. Strangely, Persson struggled to learn English, but once he reached China he had few problems with Chinese and picked it up quickly. Persson was a gifted evangelist whose “only ambition was to glorify Christ and to get souls saved.”[9] His wife Emma Persson was a zealous believer who never tired of doing good and sharing the gospel with Chinese women.

Oscar Larsson.

Oscar A. L. Larsson was a respected preacher in Sweden before he gave his life for missionary service in China. A “humble, earnest evangelist, and a never-failing peace-maker,”[10] he worked in Shanxi for tw0-and-a-half years before falling victim to the Boxer persecution. In his final letter, dated June 12, 1900, Larsson described how he and his colleague hid in the loft of a building when the Boxers came to slaughter them:

“It is evident that the peoples’ desire was to kill us. When they came inside our yard…they thought that we might be in the cellar, and so they filled it with earth; or in the well, and there they threw down our fire stoves, also many other articles…. Praise the Lord for his protecting care over us. Let us pray that the present trouble may afterwards gain a glorious victory for the Gospel.”[11]

Top: Ernst Pettersson, and Mina Hedlund.

Bottom: Anna Johansson, Jenny Lundell, and Justina Engvall.

Ernst Pettersson was the youngest of the martyrs, and had arrived in China just five months before his death. Of the other slain missionaries, four were single women aged about 30-years-old. One of them, Mina Hedlund, came to China in 1894. She spent much time in prayer and intercession, and in her last letter had declared, “I don’t fear if God wants me to suffer the death of a martyr.”[12] Anna Johansson received her missionary training in England before arriving in China in 1898. She was stationed at Zuoyun in northwest Shanxi, where she was a close friend and co-worker of Mina Hedlund. Jenny Lundell and Justina Engvall came to China together in 1899, and were still finding their feet when the Boxers barbarously slaughtered them.

The Soping chapel was burned to the ground, while “the Chinese Christians were either murdered or imprisoned. Some were robbed, and their houses burned; and up to the present they still wander homeless in misery inexpressible.”[13]

In all, 13 Swedish missionaries were killed at Soping, three belonging to the Alliance Mission and ten to the Swedish Holiness Union. The small SHU mission was still in its infancy when the massacre occurred. All that remained were two missionaries working in another province and another member, Jane Sandeberg, who was making her way home for furlough when the disaster struck. She descended the ship’s gangway in Stockholm to be handed a telegram, which read, “All members of the Swedish Holiness Union killed.” Sandeberg wrote:

“What suffering, pain, and sorrow were represented in those few words only God knows. Among those ten devoted workers who were called to lay down their lives for the Gospel, were two who, as I write, rise very vividly before me. Miss Engvall and Miss Lundell were in Yangzhou at the same time as myself, and though we only spent six weeks together, the memory of their lives will always remain with me as an inspiration and a call to seek those things which are above. Strong and faithful, meek and lowly, ready for any service, bright, cheerful, and shining for Jesus all the day—truly we who knew them thank God for them.”[14]

The devil’s plans to totally exterminate Christianity in Soping backfired. A missionary there reported of a revival in the summer of 1908:

“The nearness of God’s presence was realised in a remarkable degree…. They all knelt in prayer and immediately there were confessions made such as can only be heard when the great Searcher of all hearts is at work…. Even little children of seven and eight years of age were acknowledging their sins of disobedience and asking forgiveness.”[15]

The blood of the martyrs at Soping had become the seed of the Church.

1. Hefley, By Their Blood, 17.

2. Broomhall, Martyred Missionaries of the China Inland Mission, 145.

3. Hefley, By Their Blood, 17.

4. Forsyth, The China Martyrs of 1900, 79-80.

5. Miner, China’s Book of Martyrs, 437.

6. Broomhall, Martyred Missionaries of the China Inland Mission, 148.

7. John 1:47.

8. John Rinman, “In Memoriam—‘Martyrs of Jesus,’” China’s Millions (January 1901), 4.

9. Rinman, “In Memoriam,” 4.

10. Broomhall, Martyred Missionaries of the China Inland Mission, 149.

11. “Another ‘Last Letter’,” China’s Millions (November 1902), 156.

12. Hefley, By Their Blood, 18.

13. Edwards, Fire and Sword in Shansi, 103.

14. Rinman, “In Memoriam,” 5.

15. China’s Millions (January 1909), 7.