© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1900 - Chinese Martyrs at Taiyuan

July 1900

Taiyuan, Shanxi

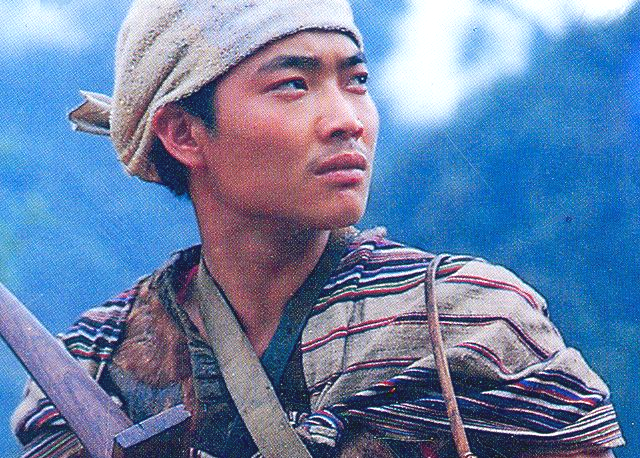

Missionary Arnold Lovitt with Chinese Christians who worked at the Taiyuan hospital. Most were martyred by the Boxers. Liu Baiyuan is standing at back left.

On July 9, 1900, a total of 46 foreign missionaries (34 Protestants and 12 Catholics) were callously massacred in the courtyard of the governor’s palace in Taiyuan, the capital city of Shanxi Province. One eyewitness remembers how he was

“startled to see them coming up the street in a long line, each with a rope tied tightly around his forehead and passing back to the next one. Men, women, and children, they formed a strange procession. And they must have been marching to their death, for that is the way they lead condemned criminals out to execution.”[1]

Hundreds of onlookers crowded into the palace courtyard to witness the macabre scene, many shouting their approval as heads were severed from their bodies. The individual stories of each missionary martyr are told separately in the following pages, but a number of Chinese Christians were also killed that day. Even though they knew the order for the missionaries to gather at the governor’s palace was a trick to kill them, some of the Chinese believers volunteered to go with them and act as their servants.

One of the Chinese martyrs was Zhang Zhengsheng who was an assistant to W. T. and Emily Benyon, the Shanxi directors of the British and Foreign Bible Society. Their work was to provide Bibles and other Christian literature to the missionary community. When the Benyon family was bound and dragged to the governor’s palace and duly hacked to death, Zhang and several other Chinese Christians went with them. Governor Yu Xian offered the Chinese believers one last chance to recant. They replied, “Don’t ask us anymore, but quickly do what you mean to do.”[2]

Liu Baiyuan.

Dr. Arnold Lovitt’s close friend and co-worker, Liu Baiyuan also received a martyr’s crown during the attack. Liu had worked as an assistant in the mission hospital for several years, proving himself a faithful and honourable Christian. Another man named Liu Hao was also killed, as was Wang Xihe, who worked for Alexander Hoddle. The final Chinese believer martyred on July 9th was a 15-year-old boy named Chang Ang, who was a student at Thomas Pigott’s school in Shouyang. When the persecution started he fled with the missionaries to Taiyuan. When Chang Ang was told to recant, he replied, “I will not; you can do as you please with me, but I will not deny the Lord.”[3] He was immediately put to the sword.

The Chinese Christians were forced to kneel down and drink the missionaries’ blood. Some had crosses burned into their foreheads with a branding iron. During the slaughter,

“a mother and her two children were kneeling before the executioner when a watcher suddenly ran and pulled the children back into the anonymity of the observing crowd. Taken by surprise, the Boxers were unable to find either the man or the children. They then turned back to the mother and asked if she had any last word. Dazed, she begged to see the face of the kind man who had taken her children. The man came forward in tears at risk of his own life. Satisfied that the children would be cared for, the mother went to her death because she would not deny her Lord.”[4]

The Taiyuan Mission Hospital before and after the Boxer attacks in 1900.

A faithful Christian named Dou Dang was nearly blind. When his friends urged him to flee he knew there was no use, saying, “I cannot flee, I shall be taken.” The Boxers gave him a chance to save his life but Dou firmly rejected their offer and was slain the next morning.

A few years after the Taiyuan massacre the famous missionary revivalist Jonathon Goforth met a scholar who was an eyewitness to the events that dreadful day. The man explained that

“He happened to be in the courtyard when [46] missionaries were driven in and herded together, awaiting execution. What impressed him most of all about these people, he declared, was their amazing fearlessness. There was no panic, no crying for mercy. Roman Catholic or Protestant—they waited on death with perfect calmness.”[5]

Just before the carnage began a little golden-haired girl aged about 13 spoke to the governor in a loud voice that carried to all onlookers:

“Why are you planning to kill us? Haven’t our doctors come from far-off lands to give their lives to your people? Many with hopeless diseases have been healed; some who were blind have received their sight, and health and happiness have been brought into thousands of your homes because of what our doctors have done. Is it because of this good that has been done that you are going to kill us?”[6]

Governor Yu Xian—The Butcher of Shanxi.

Yu Xian looked down as the truthful words of the little girl shamed him. He had nothing to say. She continued,

“Governor, you talk a lot about filial piety. It is your claim, is it not, that among the hundred virtues filial piety takes the highest place. But you have hundreds of young men in this province who are opium sots and gamblers. Can they exercise filial piety? Can they love their parents and obey their will? Our missionaries have come from foreign lands and have preached Jesus to them, and He has saved them and has given them power to live rightly and to love and obey their parents. Is in then, perhaps, because of this good that has been done that we are to be killed?”[7]

By this time the governor was humiliated, having been rebuked in front of his officials by a little foreign girl. Each word seemed to be backed by the authority of the Almighty God, and cut to the heart of Yu Xian and all present. God could have chosen an aged and wise missionary to rebuke the evil governor, but instead he chose an innocent child to do so. The moment did not last long. A soldier, standing near the girl, grabbed her hair, “and with one blow of his sword severed her head from his body. That was the signal for the massacre to begin.”[8]

Wicked men had silenced the girl’s voice, but her message lived on. Yu Xian’s own son later became a Christian,[9] while the captain of the governor’s bodyguard, who had led the slaughter, later paid a surprise visit to missionaries Jimmie and Sophie Graham in Jiangsu Province. He told them,

“We led them out into the courtyard and lined them up…. Then happened the strangest sight I have ever witnessed. There was no fear. Husbands and wives turned and kissed one another. When the little children, sensing something terrible about to happen, began to cry, their parents put their arms around them and spoke to them of Yesu [Jesus] while pointing up to the heavens and smiling.

Then they turned to face their executioners, calmly as though this thing did not concern them. They began singing, and singing they died. When I saw how they faced death…I knew this ‘Yesu’ of whom they spoke was truly God.[10]

In the days following the massacre, a “carnival of crime,” exploded around Taiyuan. One account notes,

“Nearly fifty Chinese Christians of all persuasions were killed in the next twenty-four hours. Hundreds of others were slain in the days that followed, including a colporteur who distributed tracts for [missionary Thomas] Pigott; a church probationer whose two sons attended the Baptist school; and the mother, father, and older sister of one of the schoolgirls who escaped from the hospital compound.”[11]

1. Miner, China’s Book of Martyrs, 428.

2. Miner, China’s Book of Martyrs, 110.

3. Forsyth, The China Martyrs of 1900, 364.

4. Hefley, By Their Blood, 33.

5. Jonathan Goforth, By My Spirit (Minneapolis: Bethany Publishing, 1964), 62-63.

6. Goforth, By My Spirit, 63.

7. Goforth, By My Spirit, 63.

8. Goforth, By My Spirit, 64.

9. See Goforth, By My Spirit, 62, footnote.

10. Stephen Fortosis, Boxers to Bandits: The Extraordinary Story of Jimmy and Sophie Graham, Pioneer Missionaries in China, 1889-1940 (Charlotte: Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, 2006), 39-40.

11. Brandt, Massacre in Shansi, 233.