© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1900 - Catholic Martyrs in Shanxi

June – August 1900

Shanxi

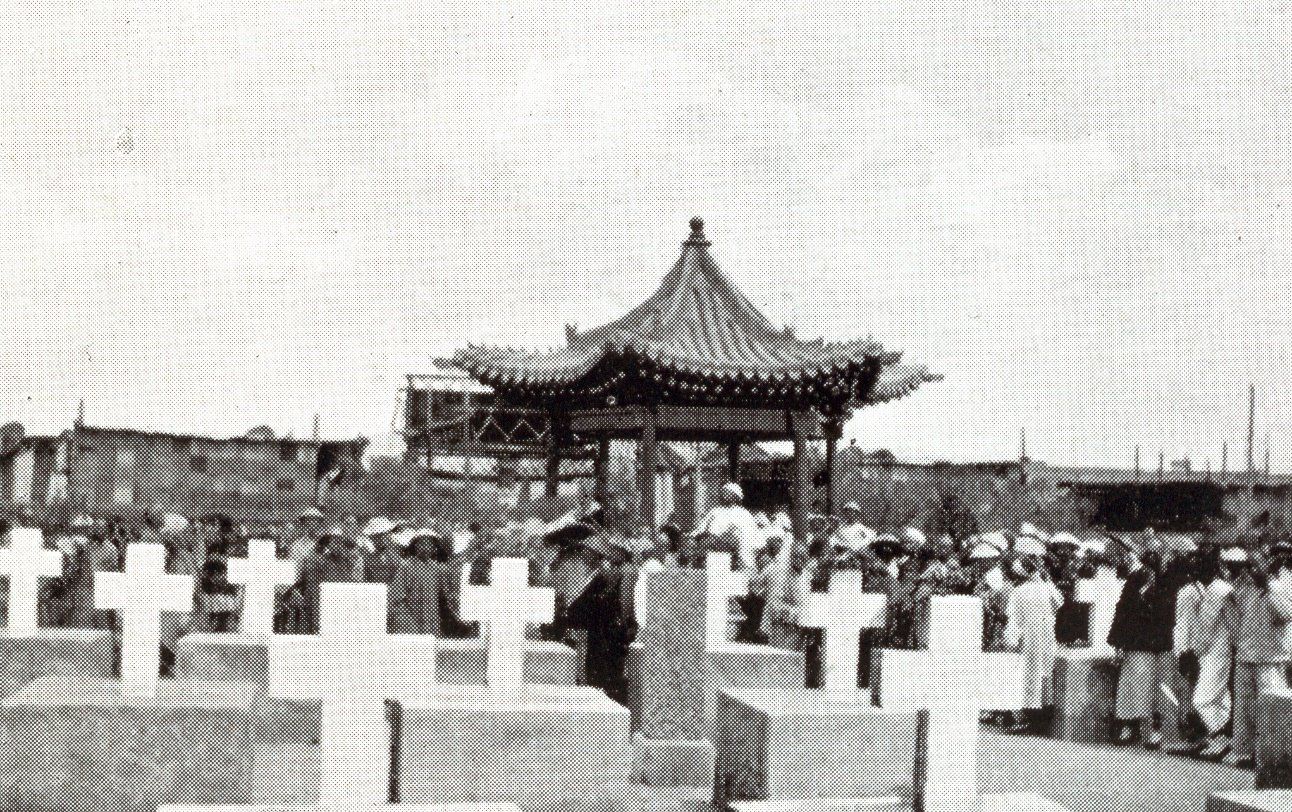

The Cemetery of Boxer Martyrs, built at Taiyuan in 1901.

The Catholic Church throughout Shanxi Province had experienced explosive growth at the end of the 19th century. The capital city of Taiyuan was home to a burgeoning church, with “about eighteen foreign priests…twenty Chinese priests, about fifteen thousand Christians, and five orphanages maintained by the Franciscan Sisters of Mary.”[1]

The first sign of trouble appeared in the month of June 1900, with Catholics being harassed and threatened. Individual believers were killed in various locations. The full force of the storm broke on July 9, 1900, when 12 priests including the Vicar Apostolic Gregory Grassi and his coadjutor Franciscus Fogolla were brutally beheaded by the Boxers in Taiyuan. The Governor of Shanxi, Yu Xian, personally struck the first blow by cutting Fogolla’s face with his sword. Some of the executioners were skilled at killing and required only one attempt to decapitate their victims, “but the soldiers were clumsy, and some of the ladies suffered several cuts before death.”[2] The bodies were left where they had fallen for the night, and robbers stripped the corpses of their clothes, watches and rings. The next day

“the heads were placed in cages for a grotesque display on the city wall. Yu Xian was without remorse and later crowed to the empress, ‘Your Majesty’s slave caught them as in a net and allowed neither chicken nor dog to escape.’ The old woman replied, ‘You have done splendidly.”[3]

Most of the Taiyuan martyrs have been profiled individually in the following pages of this book. After the foreigners had been dispatched, “the Chinese Christians were brought forth to complete the carnage. Few escaped to report the tale of horror.”[4] In all, 26 Catholics were killed at Taiyuan on July 9, 1900. The number was comprised of two bishops, three priests, seven nuns, five seminarians, and nine servants.

To recruit as many people to the Boxer cause as possible, the hateful governor “ordered all Chinese merchants, labourers, mechanics, etc., to practise as Boxers.”[5] One report found that at least 4,000 Catholics were killed by the Boxers in Shanxi Province, noting that

“when peace was again restored, a Franciscan friar named John Ricci was ordered to go through this whole mission area and collect all possible details concerning the murders and massacres. The result…was that 2,418 Causes for Beatification, on the ground of true martyrdom ‘out of hatred for the Faith’, were introduced in Rome—possibly the greatest single ‘Cause’ ever introduced in the history of the Church.”[6]

Even the Catholic children in Shanxi showed great courage when facing death. In one location as the Boxers led them away to be executed the children declared, “You are bringing us great honour! This is our day of great joy!”[7]

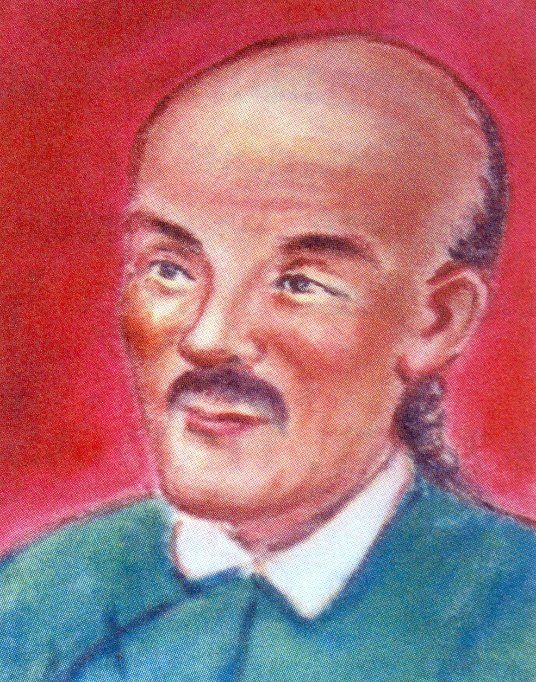

Francis Zhang Rong. [CRBC]

Francis Zhang Rong was a farmer from Qizishan village in Yangqu County. He grew up in a poor family and his father was a deaf mute. When Zhang turned 50 his wife suddenly died and he moved his family to Taiyuan, where he worked as a guard for more than ten years. Towards the end of June, as the Boxer threat drew near, Francis Zhang Rong’s son-in-law fetched a donkey to help him flee, but Zhang refused, saying he wanted to be a martyr for God. He got his wish on July 9, 1900, when he was executed along with the foreign priests and nuns. He was 62-years-old at the time.

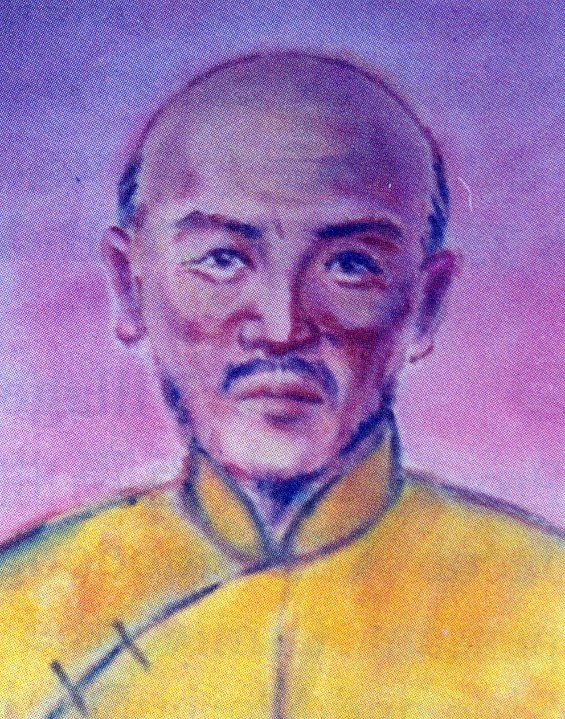

Peter Zhang Banniu. [CRBC]

Peter Zhang Banniu came from Tuling village in Yangqu County. The Zhang family had been devout Catholics for several generations, and everyone in Tuling village were Catholics. After growing up on a farm, Zhang moved to Taiyuan at the age of 40 and worked as a servant in the main cathedral. Peter refused to flee before the Boxer storm, preferring to remain with Bishop Fogolla and the other priests. The 51-year-old faithful believer was beheaded on July 9th.

It was said that “Nobody who knew him was surprised to learn that he had remained with the missionaries and gladly accepted the chance of martyrdom…. To this good man it was a high privilege to be allowed to serve our Lord in this capacity.”[8] Zhang’s son was also martyred on July 14th, reportedly after receiving a vision of his father who told him, “My son, fear not. You have only to endure a few moment’s pain and all is over. Eternal glory awaits you in paradise.”[9]

Thomas Shen Jihe. [CRBC]

Thomas Shen Jihe came from Ankao village in Huguan County. Described as a quiet man who never married, Shen was a devout Catholic and served the Church in various parts of Shanxi before becoming a servant to Bishop Grassi at Taiyuan. He was executed with Grassi and 45 other Protestant and Catholic missionaries on July 9, 1900. Thomas Shen Jihe was 49-years-old at the time.

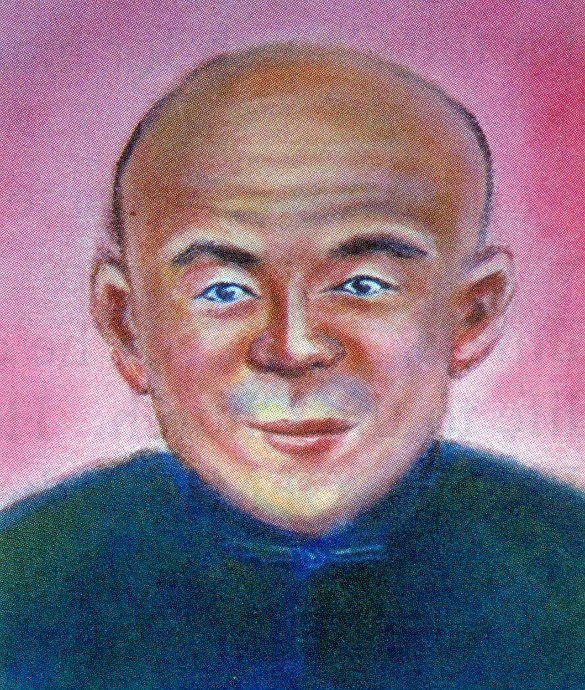

Jacob Yan Guodong. [CRBC]

Jacob Yan Guodong was a native of Yangqu County. Deciding to remain celibate for life, Yan served in the parish as a cook and was considered a hard worker who always did his job with a cheerful heart. Jacob Yan Guodong was 47 when he was beheaded at the governor’s palace in Taiyuan.

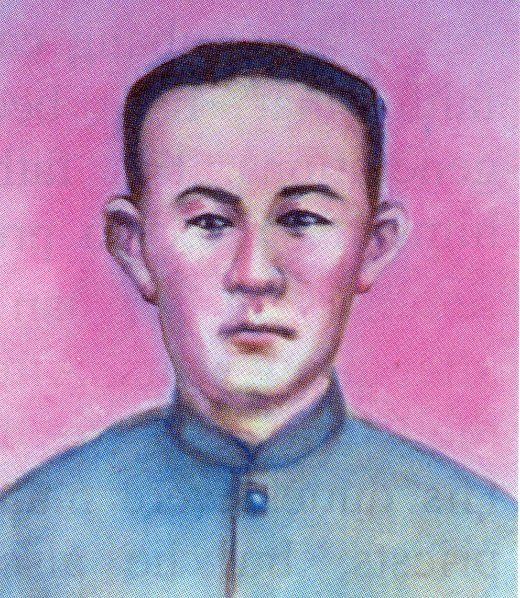

Chen Ximan. [CRBC]

Chen Ximan (Simon Chen) was born in Anyang village in Lucheng County in 1855. His family were devout Christians who had followed God for generations. Chen joined the seminary at Taiyuan while still a teenager. He fell seriously ill and had to leave early, but went to Changzhi and became a servant of Bishop Fogolla for 20 years. In 1897 Fogolla chose Chen and four seminary students to travel with him to the International Exhibition in Turin, Italy. Chen Ximan’s life was ended on July 9, 1900, when he was among the victims of the massacre at Taiyuan. He was 45-years-old.

Matthias Feng De. [CRBC]

Matthias Feng De was born in 1855 in Shuozhou County. At his baptism he was given the name Matthias. Because of a severe famine in 1893, Feng moved to Taiyuan. His eyesight degenerated around the age of 40, and his son had to provide for the whole family. Bishop Grassi had compassion on Feng and offered him a job as night watchman at the cathedral. Even when he was almost completely blind, he managed to do a good job and was known for his faithful service. Matthias Feng De was executed on July 9, 1900. He was 45-years-old at the time.

Jacob Zhao Quanxin. [CRBC]

Jacob Zhao Quanxin was born into a Christian family at Liulinzhuang village, near Taiyuan. He joined the military as a young man, and afterwards married and had two sons. Zhao gained a position as a servant in the Taiyuan church. When the bishop, priests and nuns were arrested at the end of June, 1900, Zhao “showed no concern for his own safety and carried out whatever the Bishop asked him to do. As he left his home on the morning of July 9th, Jacob told his mother, ‘If the Bishop becomes a martyr today, I shall be one too.”[10] That afternoon the Boxers arrested Jacob Zhao Quanxin and executed him.

Peter Wang Erman. [CRBC]

Peter Wang Erman was an orphan who worked in a printing factory, and was later employed as a cook at the Taiyuan seminary. In the summer of 1900 the students all headed home early because of the Boxer chaos, but the 36-year-old Peter Wang Erman remained behind at the seminary. A mob captured him on July 5th, and executed him four days later.

John Zhang Jingguang. [CRBC]

John Zhang Jingguang was a native of Taigu County. His father died when he was young, and his mother passed away while he was attending the minor seminary. In 1894, though he was just 16, Zhang attended the major seminary in Taiyuan. When the threat of persecution approached in 1900, Zhang prepared himself and encouraged his fellow students to accept martyrdom.

After a Protestant church was burned down in the city on June 27th, all the seminarians were instructed to return home, but John Zhang Jingguang decided his life could better glorify God by staying. He was arrested on July 5th along with the foreign missionaries and a number of his fellow seminarians. At the time Elias Facchini noticed that Zhang “played around the prison-yard with the gaiety and frolic of a boy about to go home on vacation. So he called him and said, ‘John, John, remember this is not the time for amusement.’ ‘Why not, Father?’ said the youth. ‘If we are put to death shall we not go to heaven?’”[11] John Zhang Jingguang was brutally put to death four days later.

Philip Zhang Zhihe. [CRBC]

Philip Zhang Zhihe was born at Lin Xian County in 1880. At the age of 16 he was admitted to the minor seminary at Dong’ergou. Described as “a hardworking student with a strong will, he was not especially gifted, but was well-mannered, honest and responsible.”[12] He later attended the major seminary at Taiyuan, and experienced martyrdom on July 9, 1900. Philip Zhang Zhihe was just 20-years-old.

John Zhang Huan. [CRBC]

John Zhang Huan was born in 1882 in Yangqu County. From his early childhood he was interested in the things of God, displaying a spiritual maturity beyond his years. He later studied at the seminary at Taiyuan. When the students were advised to return home before the Boxer violence started, John Zhang Huan did so, but he felt uneasy in his spirit and returned to Taiyuan a short time later, determined to be a martyr. He was one of those remorselessly massacred on July 9, 1900.

John Wang Rui. [CRBC]

John Wang Rui was just 15 when he was martyred for Jesus Christ. Born on February 26, 1885, at Xinli Village in Wenshui County, he displayed a firm faith in God from an early age and was given the name John at his baptism. At the minor seminary he soon became renowned for his angelic voice, and was often asked to sing for the edification of the other students and staff. Chosen as one of several Chinese students to accompany Bishop Fogolla on his trip through Europe between 1897 and 1899, John Wang Rui attended the seminary at Taiyuan upon his return to China. When advised to flee ahead of the savage Boxers, the young man fearlessly declared, “I shall be a martyr for God.”[13] He was butchered in cold blood on July 9, 1900.

James Zhao Zhunsen was a humble labourer who loved the Lord. When the missionaries at Taiyuan were arrested he visited and remained at the prison until evening every day. On July 8th he told his wife that he would not return the following day. When she asked why he remained silent, and spent the whole night in fervent prayer. The next morning he gave a tearful farewell to his mother, wife and children, saying, “I am going now to see the bishops; if they are executed today, I intend to lay down my life with them.”[14]

Soon after he arrived at the prison the guards started binding the believers to be taken for execution. Some of the soldiers had served in the military with Zhao and refused to bind him. The indignant disciple complained, “‘I am a Christian. You have no right to separate me from the others.’ The guards, admitting the manly courage of James, bound him along with the others. He was taken before the governor, asked to apostatise, and upon refusing to do so, he was duly put to death.”[15]

The July 9th massacre was not the end of persecution for the Catholics at Taiyuan, but rather it signalled the beginning. On the day after the massacre (July 10th), the Taiyuan Cathedral was attacked,

“and 49 converts massacred, most of the women and girls being spared, and subsequently sold to Boxers and their friends…. In the immediate vicinity the Roman Catholics suffered severely, 200 being killed in one village alone and it is estimated in the whole province they lost about 8,000.”[16]

In some cases God intervened and saved the lives of those who stood up for the truth. In the days following the massacre an additional 70 Chinese Catholics were rounded up from the suburbs of the city and brought before the governor. He told the captives, “You rebellious subjects! I have killed the foreigners, now you must give up the foreign religion.” The elder believers in the group replied, “We are trusting the Lord Jesus to save us from our sins, we cannot deny him.” Yu Xian asked the group, “Why will you die? You are Chinese people, and I do not want to kill you.” Finally the leaders of the 70 Christians, on behalf of the whole group, reiterated their stand:

“‘We are trusting in the Saviour to save us for ever, we cannot forsake him.’ Again condemned…some of the younger members of the band exclaimed, ‘We will not recant.’ They were sent to the gate. On reaching it the governor said, ‘Pick out those two maidens.’ They happened to be Roman Catholics, about 17-years-old, and immediately they were beheaded. Their blood was caught in a basin, and mixed with water, of which the remaining 68 were made to take a sip, after which they were liberated.”[17]

Another group of Christians were holed up inside the Taiyuan house of a catechist named Matthias Li Jinzhao. On July 14th the Boxers raided Li’s house and arrested everyone present. When they began to bind the Christians one of them protested, “You have no need of chains or ropes; we will go freely wherever you wish.”[18] After being threatened with death, one of the group declared, “Here we are now. Put us to death here. We have nothing left in this world. Why send us back to the homes which you have already destroyed?”[19] Back at Li’s house, the group was cast into gloom when Matthias himself, who had been a tower of strength up to that point, began to waver and proposed a compromise with the Boxers to secure their freedom. He claimed it was possible to outwardly strike a deal with their enemies while remaining true believers in their hearts. As he prepared a list of the names of all present to be given to the Boxers, every other believer strongly objected and fell to their knees in prayer. As Matthias Li Jinzhao made his way towards the Boxer headquarters with list in hand,

“while passing the ruined cathedral he was suddenly sized with terror and amazement. He saw walking towards him, vested in full pontificals, Monsignor Grassi who had been martyred only a few days before! The bishop came up to him, placed his hand on his shoulder, and said rebukingly: ‘How is it, catechist, that you show such bad example to the Christians? Return immediately and I promise that you will soon be with me in heaven.’ Overcome with fear and sorrow, Matthias hurried back to the house and, rushing into his companions…threw himself on his knees and related with tears and sobs what had occurred: ‘Oh, pray for me,’ he cried, ‘pray for me, all of you, for I am a wretched sinner.’”[20]

Encouraged by the vision, Li was one of 42 Catholic men and boys slain by Boxer swords the following day. The Christian women were allowed to go free after the governor’s wife had pleaded for females to be spared. One of the murdered men was Anthony Guan Lun. Before being butchered, Guan looked towards his wife Christina and exhorted her to take care of their two surviving daughters, aged 15 and 12. Christina was forced to witness the deaths of her husband and two sons, Anthony and Francis, aged five and 10-years-old respectively. Francis

“cried out when his father was put to death: ‘Mama, mama, what are they doing to daddy?’ ‘Close your eyes, darling, and keep quiet,’ she sobbed. The little fellow obeyed, and covered his eyes with his hands, but soon afterwards whispered, ‘Mama, I’m thirsty.’ ‘Wait a moment, darling,’ replied the mother, ‘and our Blessed Lord will bring you a drink.’ She had hardly said the words when a Boxer cleft the innocent child’s skull with his sword. The heroic Christina now clasped her youngest infant, only nine-weeks-old, to her bosom while the Boxers stood around her jeering at her tears.”[21]

Unfortunately, the diabolical experience was not yet completed for Christina. A Boxer saw the infant in her arms and callously asked, “Is that a boy or a girl?” Christina hesitated before answering. All she had to say was “It’s a girl,” and the baby’s life would be spared. But even under such duress she would not lie to her persecutors. With total “abandonment to God’s will, she forced out: ‘It’s a boy.’ ‘Put him on the ground,’ yelled the Boxer. She did so, and as she held the little one before her the Boxer’s sword pinned it to the earth. Even then the brave woman did not flinch. God was very near to her in that supreme trial.”[22]

There was no place in the entire province where the Boxer persecution did not reach. Even remote mission stations in the Luliang Mountains were affected, and hundreds brutally put to death. The first missionary to return to Shanxi in 1901 reported that in Taiyuan alone,

“Anything from 1,500 to 2,000 Christians have been massacred; the churches and the residences have been destroyed or seriously damaged, the Christians’ houses had been burned down and entire villages completely razed to the ground…. In Taiyuan a church, in which about fifty Christians had gathered to pray, was surrounded by the Boxers who fell on the Christians like wild animals and slaughtered them. Mothers could be seen offering their babies for slaughter in the fear that a worse fate should befall them if they remained alive…. Massacres had been perpetuated in every village and the survivors were living in squalid misery.”[23]

The diabolical carnage in Shanxi did nothing to stop the advance of the kingdom of God. In 1950—just after the advent of Communism—Taiyuan Diocese numbered 40,749 Catholic in 24 churches.[24] Despite decades of Communist persecution and oppression, when seven Catholic churches were officially reopened at Taiyuan in 1981, 35,600 people emerged to celebrate mass.[25] By 2000 one survey found there were more than 70,000 Catholics in Taiyuan alone. [26]

1. Latourette, A History of Christian Missions in China, 510.

2. Brandt, Massacre in Shansi, 232.

3. Hefley, By Their Blood, 16.

4. Hefley, By Their Blood, 16.

5. Edwards, Fire and Sword in Shansi, 104.

6. John Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900: Tertiaries of St. Francis (Melbourne: The Australian Catholic Truth Society, 1955), 5.

7. Smith, China in Convulsion, Vol.2, 698.

8. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 12.

9. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 12-13.

10. CRBC, The Newly Canonized Martyr-Saints of China, 32.

11. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 11.

12. CRBC, The Newly Canonized Martyr-Saints of China, 35.

13. CRBC, The Newly Canonized Martyr-Saints of China, 38.

14. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 13.

15. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 14.

16. Edwards, Fire and Sword in Shansi, 174-175.

17. Mrs. Pruen, The Provinces of Western China (London: Alfred Holness, 1906), 210-211.

18. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 15.

19. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 15.

20. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 15-16.

21. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 17.

22. Ricci, Chinese Martyrs of 1900, 17.

23. From the profile of Caio Rastelli on the www.xaviermissionaries.org website.

24. www.catholic-hierarchy.org

25. Jean Charbonnier, Guide to the Catholic Church in China (Singapore: China Catholic Communication, 1989), 159.

26. UCAN (Union of Catholic Asian News), June 15, 2000.