The Boxer Rebellion (1900)

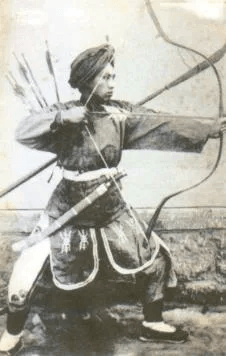

A postcard showing a Boxer from Shandong.

In 1899 a terrible flood of the Yellow River inundated the entire Shandong Plain, drowning and misplacing millions of people. Coming on the back of years of severe drought and humiliation at the hands of foreign military powers, the flood was a turning point. The religious leaders of the day declared that the woes being heaped upon the people of Shandong were because the spiritual balance had been upset, and the only way to placate the spirits was to rid the province of foreign influence.

For decades a secret group known as the White Lotus Society had been active throughout Shandong. A subgroup of the Society called the Yi He Quan (literally 'righteous harmony fists') came to be known in the English-speaking world as ‘Boxers', because of their practice of using boxing drills for physical training.

They launched the notorious Boxer Rebellion in 1900, resulting in the slaughter of thousands of Christians throughout China. It was not until after the advent of Communism that the White Lotus Society finally subsided, although their dark legacy can still be seen today in the triads of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other overseas Chinese locations. One report claimed that an offshoot of the White Lotus Society was still operating in Shandong in the 1960s. 1

Many missionaries in Shandong warned of the storm clouds of violence they saw gathering on the horizon. Using cautious words of restraint in keeping with the Victorian era in which she wrote, Ada Mateer described the demonic nature of the Boxer movement:

"The Boxer organization started in Shandong. Its motto, after leaving the confines of its native village, was 'Uphold the Qing (the ruling dynasty) and exterminate the foreigner.' Their drill consisted in burning incense before a tablet and then working themselves up by gymnastics, etc., to a state where they were no longer masters of themselves, but became unconscious. After remaining in this state for some time they would rise, declaring themselves possessed of the spirit of one of the old heroes of antiquity.

In this state they could perform great feats, but the chief mark of distinction was that they were invulnerable. Swords would not hurt them, and they could knock their heads on the ground until a great lump appeared, but never feel it. This lump on the forehead became a distinguishing mark. It was enough to make one think of the mark of the beast and to make one wonder whether, after all, these fellows were not right in their claims to be possessed. Was this not a gathering of the forces of the evil one, for one mighty struggle?" 2

The Tragic Death of Sidney Brooks

Sidney Brooks.

The British missionary Sidney Brooks is widely recognized as the first Christian martyr murdered by the Boxers. He died at Tai'an in Shandong in the last week of 1899, even though the Boxer Rebellion is generally recognized to have commenced in the summer of 1900.

Brooks arrived in China in 1897, accompanied by his sister. He settled at Pingyin in southwest Shandong, while his sister established her home at Tai’an, approximately 150 miles (243 km) away.

Brooks saw little of his sister, as he threw himself into language study and preaching. She married a missionary, H.J. Brown, and the two newlyweds had only just returned from their wedding in England, when Brooks excitedly made the journey to Tai’an, where he enjoyed a wonderful Christmas break with his family members.

On December 28, after lovingly saying goodbye to his sister and brother-in-law, Brooks mounted his donkey for the arduous ride home to Pingyin. At ten o’clock the next morning, as he rode through Zhangjiadian, “there was a terrible commotion in the village and about 30 Chinese brandishing big knives and yelling like demons came rushing toward him.” 3

Brooks was startled, as he had no idea what he had done to deserve such a hostile reception. He found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time, and when the anti-foreign Boxers saw a white man calmly riding his donkey through their village they decided to make the Englishman the first-fruits of their blood orgy.

Brooks realized his only hope of survival was to flee, so he forced his mount into a faster speed, but the pursuing Boxers soon overtook him. Brooks leaped from the beast and ran into a temple, hoping he would be safe inside a house of religion. That hope proved futile, for the temple headman had seen the chase and refused to protect the missionary. He grabbed Brooks and tried to push him off the temple property. In self-defense Brooks struck the man to the ground. This action had the same effect as striking a beehive with a large stick, for

“Instantly the priests of the temple became howling dervishes. They rushed upon him from all sides, and, with his back to the wall, he used both his right and left arms with telling effect. One priest, rushing in under his guard, was caught up in both his strong arms, whipped off the ground and thrown back among his countrymen, knocking them right and left.” 4

The bloodthirsty Boxers waited impatiently outside the temple for the condemned man to be brought out. Finally, by sheer weight of numbers Sidney Brooks was overwhelmed by the monks, who “pinioned his arms, and dragged and pushed him to the door. Then they hurled him into the arms of the Boxers. The latter set upon him, striking him on the head with their knife handles and pricking him with their blades. They kicked him, punched him, and tore his face with their nails.” 5

Brooks tried to reason with the men, offering them money for his release. They laughed and spat in his face. The only thing they wanted was his blood. The missionary was stripped to his blood-soaked underwear and made to wait, despite the temperature being below freezing. The poor man

“shrieked aloud in his agony, but his sufferings only delighted the yellow fiends. Somehow, out of utter desperation and terror, Brooks managed to free his hands and raced away. The callous Boxers laughed at this development, focusing their attention on their meal. Three horsemen were sent in pursuit and soon overtook him. Brooks jumped into a deep gully, taking his last stand. When the Boxers came upon him, he again offered money and begged piteously for his life. Knives in hand, they stood over him and taunted him. They waved their weapons and laughed at him, and circling about him like vultures, sprung upon him until he fell dead. They then cut off his head and bore it back to their companions in triumph.” 6

It later emerged that Brooks had told his sister and brother-in-law of a premonition he had of his own martyrdom. At Christmas, they said that

“He had just had a disturbing dream. In it, he was back in England and in passing through the college where he received his education he read again the tablet bearing the names of all who had gone out from that school as missionaries together with the name and field and the date of departure; and that while looking through the building he saw another tablet, bearing the inscription: ‘To those who were martyred for the Faith.’ On the tablet he saw plainly his own name.” 7

Brooks was the first Christian in Shandong martyred by the Boxers, but strangely, he was to be the one and only Evangelical missionary killed in the coastal province. The Governor of Shandong saw the threat the Boxers posed, and sent large numbers of troops to drive the insurgents out of the province during the winter and spring of 1900. Most of the Boxers were forced into Hebei and Shanxi, which subsequently ended up being the provinces with the highest number of slaughtered Christians during the Boxer Rebellion.

The Plight of Chinese Christians

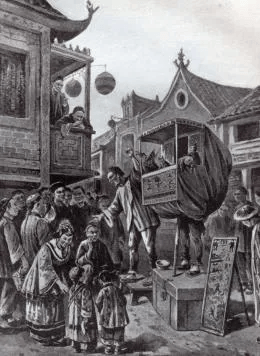

A sketch of Boxers inciting people to attack and kill foreigners.

Although all remaining foreign missionaries in Shandong managed to leave safely, the local Chinese believers paid a heavy price for Christ. A British Baptist missionary, E. W. Burt, reported that in one location,

“The converts’ homes and places of worship were burnt. They themselves were harmed and scattered, hiding in caves of the hills, and crouching among the tall millet, not daring to show themselves. Over 120 died a martyr’s death. Others did not prove so steadfast. Some of the pastors recanted. In one single village no less than 37 men and women sealed their testimony with their blood. No doubt ultimately this severe baptism of blood purified the Church, weeding out the unworthy and the self-seeking and deterring others with mixed motives from joining it.” 8

A report in the Missionary Herald noted the killings in Shandong was concentrated in the Zouping area, and declared,

“Zouping is now for ever memorable in the annals of Christian history in China, as the scene of the martyrdom of many scores of Christian men and women...who died for the sake of ‘the Name’. One hundred and seventy six in all were cruelly done to death, slain for the Faith. For many anxious days and weeks, hundreds were hiding in the open fields from those who sought their lives. They returned to find houses burnt, property stolen and crops reaped.” 9

The church in the northwest Shandong village of Zhujia had experienced powerful revival in the years preceding the Boxer Rebellion. A missionary reported that “a whole region, hitherto closed to the gospel, suddenly and unexpectedly…was thrown open.” 10 When the Boxers attacked Zhujia they slaughtered 28 of its church members.

A Christian woman named Zhao lived in the town of Binzhou. When the Boxers came near, she left her village and hid in a relative's home. The Boxers were informed, and immediately went and seized her. When she realized there was no chance of escape, Zhao bravely followed the Boxers to a field outside the village, where

“They ordered her to kneel, facing the southeast, that she might worship their gods. She refused to turn her face in that direction, saying, ‘Since I have learned the Christian doctrine I do not worship devils, but only the true God.’ So she knelt in a different direction.” 11

Sister Zhao’s defiant act enraged the Boxers, who immediately sliced her body to pieces with their sharp swords. Finding that the gruesome act was not enough to placate their anger, they then burned her body to ashes.

Evangelist Sun.

When the Boxer Rebellion erupted in the summer of 1900, the Church at Pingdu was already well established. One of the most effective evangelists in the congregation was a man named Sun. He and his two sons managed to flee from the Boxers, taking refuge at an inn owned by a church member. The Boxers soon arrived and seized Sun and his two sons. They were bound with cords and roughly dragged to the magistrate’s office for interrogation. When asked if he was a Christian, Sun replied with a question of his own, “I study the doctrine, worship God, and obey the laws of the empire. Why should I be killed?” 12

The magistrate did not want to kill the bold preacher, so in a bid to appease the bloodthirsty Boxers he ordered Sun and his sons be beaten with 300 heavy strokes and thrown into a dungeon. The severe punishment left the three Christians struggling to breathe and badly disfigured, but it was not enough to satisfy the Boxers. The next day they went to the dungeon and dragged the three faithful men outside the city. As the sword was lifted above his head, Evangelist Sun knelt down and cried out, “Heavenly Father, receive my spirit!”

Twenty other Christians at Pingdu were seized and offered escape if they would deny their God and worship the idols. When they refused, their ponytails were "tied to the tails of horses, and they were dragged 25 miles to Laizhou where most were killed.” 13

The Boxers commanded a young Christian woman named Yu to leave her house and be killed. “Wait until I have combed my hair,” she replied. She calmly combed her hair and changed her clothes, in preparation for meeting her Savior. She then asked her persecutors, “Where do you wish to kill me?” The Boxers dragged Yu outside the village to an intersection, but when they tried to force her to kneel down she refused, saying, “‘I cannot worship the false gods whom you reverence.’ She lifted up her soul in prayer; but the Boxers did not wait until the prayer was ended.” 14

Those Shandong Christians who did survive faced extreme hardship. Thousands of Christians’ homes were burned to the ground, and all their possessions seized. Many were reduced to begging for years to come. When the missionaries returned, much of their time was spent trying to help the impoverished believers recover from their terrible ordeal. Hunter Corbett reported from Yantai,

“I found suffering in every place. Many trying to live on corncobs, the dried vine of the sweet potato, bark, and leaves of trees, roots, etc. I found the Christians hopeful. They feel that God had not forsaken them, but had heard and answered prayer. Wonderful grace was given to our persecuted people. They stood firm and are not giving up the Christian life.” 15

When the pain and devastation caused by the Boxers started to fade, a thorough survey of Shandong found that 245 Chinese Evangelical believers had been killed throughout the province. 16 Thousands of Christians had their homes burned to the ground, and many chapels were also destroyed. The Church in Shandong had suffered a serious setback.

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book 'Shandong: The Revival Province'. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. “Introducing the Jesus Family,” Bridge (July-August 1992), p. 8.

2. Mrs. A.H. Mateer, Siege Days: Personal Experiences of American Women and Children During the Peking Siege (New York, NY: Fleming Revell, 1903), p. 23.

3. Harold Irwin Cleveland, Massacres of Christians by Heathen Chinese and Horrors of the Boxers (New Haven, CT: Butler & Alger, 1900), p. 538.

4. Cleveland, Massacres of Christians, p. 539.

5. Cleveland, Massacres of Christians, p. 539.

6. Cleveland, Massacres of Christians, p. 539.

7. Isaac C. Ketler, The Tragedy of Paotingfu: An Authentic Story of the Lives, Services, and Sacrifices of the Presbyterian, Congregational and China Inland Missionaries who Suffered Martyrdom at Paotingfu, China, June 30th and July 1, 1900 (New York, NY: Fleming Revell, 1902), p. 325.

8. Cliff, A History of the Protestant Movement in Shandong Province, pp. 210-11.

9. Cited in Cliff, A History of the Protestant Movement in Shandong Province, p. 211.

10. Cliff, A History of the Protestant Movement in Shandong Province, p. 134.

11. Luella Miner, China’s Book of Martyrs: A Record of Heroic Martyrdoms and Marvelous Deliverances of Chinese Christians During the Summer of 1900 (Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press, 1903), pp. 165-6.

12. Miner, China’s Book of Martyrs, p. 162.

13. James & Marti Hefley, China! Christian Martyrs of the 20th Century (Milford, MI: Mott Media, 1978), p. 32.

14. Miner, China’s Book of Martyrs, p. 188.

15. Charlotte E. Hawes, New Thrills in Old China (New York, NY: George H. Doran Company, 1913), p. 105.

16. See table in Cliff, A History of the Protestant Movement in Shandong Province, p. 222.