Lottie Moon (1840 - 1912)

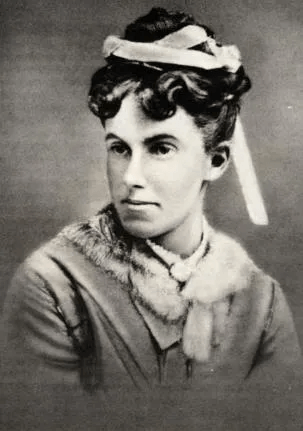

Lottie Moon in 1873, aged 33.

The Southern Baptists were the first to work in the Pingdu and Tengzhou (now Penglai) areas of Shandong Province in the early 1870s. The most famous of their missionaries was the diminutive American Charlotte ('Lottie') Moon, who served in Shandong from 1873 to the time of her death by starvation in 1912.

Born into a wealthy Virginia family in 1840, Moon met Jesus Christ at the age of 18 after she was unable to sleep due to a barking dog. Wide awake with nothing to do, she decided to honestly examine the claims of Christ. A short time later she dropped to her knees in prayer and dedicated her life to the Living God.

Moon's desire to serve God in China was delayed by the final years of the American Civil War, but her vision was ultimately fulfilled and she became one of the first unmarried women ever sent to the mission field by the Southern Baptists. After arriving at Yantai, the new recruit headed overland to Penglai—a trip of two days.

Lottie's entire 40-year missionary career was spent in Shandong, first at Penglai and later in Pingdu. She spent countless hours traveling around the province in a shengche ('rope cart')—a contraption that was described as

"like a covered wagon slung on poles instead of wheels. It was a sort of basket turned on its side with mouth pointed forward. It was covered by a thick cloth which more or less weather-proofed the inside. The shengche poles were fastened on mules in front and behind. One or more drivers walked beside to guide the beasts through narrow, rutted trails. Inside the housing, the passenger lay back on mountains of bedding to cushion the jolts. The ride was violent and often sickening." 1

Lottie Moon often traveled around the Shandong countryside in this 'shengche'.

Soon after settling into her work, Moon's contribution to the cause of the gospel in China began to emerge through her writings and passionate challenges to church members in her homeland. Despite standing just four feet, three inches (1.3 meters) tall, Lottie's words packed a powerful punch. Not content just to send letters to private individuals, she wrote directly to magazines and newspapers, which were glad to publish her unique and politically-incorrect views. Numerous memorable quotes flowed from her pen.

One of Lottie's first blunt rebukes of the Southern Baptist churches came just months after her arrival in China, when she wrote,

"It is odd that a million Baptists of the South can furnish only three men for all China. Odd that with 500 preachers in the state of Virginia, we must rely on a Presbyterian to fill a Baptist pulpit here. I wonder how these things look in heaven. They certainly look very queer in China." 2

As Moon matured as a believer her challenges became even more piercing. She even rebuked her own mission board for sending missionaries to Africa, while many Baptist church members in the southern states continued to oppress black people.

The hard-hitting nature of her challenges shocked many American church-goers, causing consternation among the status quo. She was accused of being a radical feminist, and subtle pressure was brought to bear to try to remove her from the mission field.

In Shandong, Lottie was admired for her sharp sense of humor and ability to make her points for God. Deeply troubled by the daily barrage of spiteful calls of "Foreign Devil!" everywhere she went, she adopted a unique response to the taunts. Whenever a child called her a foreign devil,

"She took the boy or girl to his or her mother and asked that the child be taught good manners. If a woman goaded her, she would turn and retort, 'Do not call me a devil. We are both women, and we both come from a common ancestor. If I am a devil, what does that make you?' With this approach, slowly the attitude of the taunters began to change." 3

Loneliness

At one stage Lottie Moon was engaged to a highly-educated young man, Crawford Toy, who claimed to have a call to missions. She broke off the engagement, however, when she learned that he had embraced Darwin's theory of evolution. Toy went on to become a professor at Harvard University, while Moon was left in China to, in her words, "plod along in the same old way."

Years later when asked if she had ever fallen in love, Lottie replied, "Yes, but God had first claim on my life, and since the two conflicted, there could be no question about the result." 4

Lottie Moon often found missionary life excruciatingly lonely, and she struggled with depression. Four years after arriving in China she wrote to her mission board, "I am bored to death living alone. I don't find my own society either agreeable or edifying.... I really think a few more winters like the one just past would put an end to me. This is no joke, but dead earnest." 5

Conflict on the Field

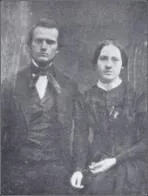

Tarleton and Martha Crawford.

From the time of her arrival in China, Lottie had struggled to get along with other missionaries, and she frequently clashed with her supervisor, Tarleton Crawford. A man who mixed business pursuits with his missionary work, Crawford constructed a tower in which he planned for Lottie to live with her sister, Edmonia, who had preceded her to Shandong by a few years. The local Chinese, who lived in walled compounds, rioted in protest against the missionary's tower. The only reason they could imagine why someone would build a high tower was to look down on them and spy on their wives and daughters.

To quell the rioters, who were armed with sticks and stones, Crawford pulled out a gun and aimed it at the crowd, causing the people to flee for their lives. Lottie was shocked and confused at how a servant of Jesus Christ could threaten to use a weapon against those he was supposed to serve.

To make matters worse, one day her sister Edmonia lowered her voice and whispered, "People in America might think it's proper for single women like you and I to live with a married couple, but do you know how the Chinese view it? They think I am Tarleton Crawford's second wife, and I am sure they will think you are his third." 6

After serving in China several years under such trying circumstances, Edmonia's physical and mental health reached breaking point, and she was sent home to Virginia to recuperate. She never set foot in China again, and Lottie deeply mourned the loss of her sister.

By 1885, after a dozen years in China, Lottie found herself at her wits-end. She had grown tired of Crawford's "ever-repeated annoying demands and constant humiliation, as he tried to make all around him stultify themselves by absolute submission." 7 Crawford, from a Kentucky farming family, was a notoriously difficult person to get along with. A historian wrote,

"Forty of his 50 preaching years were spent in Shandong Province, mostly at Penglai.... He never liked the Chinese very much, and sometimes one feels that there were not many people whom he did like. Fortunately, perhaps, Crawford was so intemperate in urging his personal enthusiasms on other Southern Baptists that he finally 'threatened the very existence of the Convention,' not to mention its China missions, and his church had—as he termed it—to 'refrigerate' him." 8

A Breath of Fresh Air

Desiring to flee the toxic atmosphere in Penglai, Lottie decided to relocate inland to Pingdu, where she planned to preach the gospel to anyone willing to listen—male or female. In Chinese society at the time it wasn't considered proper for a woman to address a man directly. Lottie directed her messages to the women, but their husbands invariably found a way to listen too, out of sight but not out of sound.

Moon seemed to be on the verge of resigning her post and returning home in frustration when, in 1887, three Chinese men from the small village of Shaling knocked on her door and begged her to come to their village and teach the "new doctrine."

Although she had long clashed with Tarleton Crawford's leadership, Lottie was good friends with his long-suffering wife, Martha, who hailed from Alabama. Martha was a zealous evangelist, having presented the gospel to the women and children of 315 different villages in a single year. 9

Lottie sent a message asking Martha to meet her in Shaling. On the journey she prayed fervently, hoping the trip would not be in vain and that they would meet some people with hearts open to the claims of the gospel. Moon was soon shocked by the reception that greeted her.

As she entered the village of about 50 households, "Many people rushed out to meet Lottie. 'It is the lady with the heavenly book!' exclaimed one man. 'Yes, and she will tell us how our sins may be evaporated!' shouted another man, waving wildly at Lottie." 10

For days the two female missionaries answered questions about Jesus Christ from the spiritually hungry people of Shaling. The first evening flew by, "but no one wanted to go home. Long into the night the men and women shouted out questions, which Lottie did her best to answer. The crowd left the house only when Lottie was too hoarse to speak anymore. The crowd the next night was even larger, and larger still the night after that." 11

The duo left Shaling greatly encouraged, having experienced a breath of fresh air. Lottie wrote that she had found "something I had never seen before in China. Such eagerness to learn! Such spiritual desire!" 12

Buoyed by this success, she excitedly wrote home, "I have never gotten so near the people in my life as during this visit. I have never had so many opportunities to press home upon their conscience their duty to God and the claims of the Savior to their love and devotion. I feel more and more that this work is of God." 13

A thriving church gradually formed in Shaling. The new believers were distraught, however, when they discovered Lottie would be taking a summer break and her mission board hadn't appointed anyone to replace her. Several letters from China were received at the Southern Baptist headquarters in Virginia. One letter said,

"For more than ten years I have known of this doctrine but did not inquire into it. On having an opportunity to inquire, immediately I truly believed. I am deeply in earnest in learning, but there is no pastor here to teach. I earnestly look to the Venerable Board to send out more teachers.... The light of this mercy will shine everywhere, and gratitude will be without limit. I am longing for it as if, when the earth is dry, rain is longed for." 14

An elderly man listened to the preaching at Shaling village and was presented with a New Testament by Lottie Moon. He was unable to read, so he asked his cousin, a Confucian scholar named Li Shouding, to read it to him. Li set out to mock the teachings of Jesus, but was struck by the words of life as he read. Li Shouding believed and was baptized in 1890, going on to become the most outstanding evangelist in north China. He was greatly used by God and personally baptized more than 10,000 converts, including over 1,000 in the Pingdu area alone.

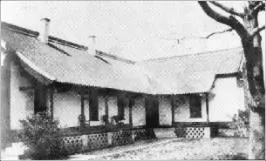

Lottie Moon's home in Penglai.

The experience at Shaling was a turning point in Lottie Moon's life. For the next two decades she spent part of the year traveling through the villages of Shandong doing evangelism, and part of the year at her home in Penglai, where she trained new missionaries and continued to write provocative letters to mission magazines back in America. Many responded to her call to missionary service, and her influence was so far-reaching that the Southern Baptists established an annual Christmas offering to enable them to recruit more workers. It was later renamed the Lottie Moon Offering in her honor.

'You Will Have to Kill Me First'

The gospel expanded quickly throughout Shandong, bringing with it an increase in persecution. The Christians refused to participate in ancestor worship rituals, infuriating their families and communities. In 1890, at the height of the persecution, a bloodthirsty mob surrounded an elderly Chinese Christian named Tan Huopang and were on the verge of beating him to death. The diminutive missionary rushed to the scene and refused to bow to the mob's intimidation. Instead,

"Lottie fought her way to the center of the crowd. She gasped when she saw Tan Huopang kneeling with his head in his hands. Blood streamed from his face and he was being kicked and spat upon. Lottie shoved several men with sticks out of the way and ran to his side.

A gasp rose from the mob, and then the people fell silent. Lottie did not know how long the silence would last, so she began to yell out... 'If you try to destroy the church here, and the Christians who worship in it, you will have to kill me first. Our Master, Jesus, gave His life for us Christians, and now I am ready to die for Him'....

One of Tan Huopang's nephews yelled back, 'Then you will die, foreign devil!' With that he lifted a huge sword over his head and aimed it at Lottie. Then, inexplicably, his hand dropped to his side and the sword clattered onto the cobblestone road. With that, the mob's energy appeared to drain, and slowly the people wandered away." 15

Lottie Moon in 1901, aged 61.

"Oh, How She Loved Us"

As the years progressed, frequent plagues of cholera and smallpox blighted the Shandong population, and the continual cycle of floods and famines taxed the missionaries' energy and resources. The overthrow of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 brought chaos to the whole country, resulting in mass starvation and misery.

Lottie and other Christians quickly established a relief service to help as many people as possible. Her sensitive heart was torn by the suffering of those around her, especially the Christians she had played such a crucial role in bringing to the faith. She pleaded for funds from the United States, but the economy back home was struggling and the Southern Baptist mission board was heavily in debt.

Deeply upset by the lack of assistance, Moon decided to set an example of personal sacrifice. If those back home were too pre-occupied with their own problems to care, she would leave no stone unturned in her efforts to help the afflicted people of Shandong. She emptied her bank account and gave away as much of her food as possible, feeding hundreds of starving people. She wrote a note in her bank book: "I pray that no missionary will ever be as lonely as I have been."

With no help arriving from home, Lottie was plunged into depression. She stopped eating regularly and her physical and mental health rapidly deteriorated. Other missionaries grew deeply concerned and summoned a doctor. Although she now weighed a mere 50 pounds (23 kg), the missionaries were shocked when the doctor announced Moon was starving to death and that little could be done to arrest her condition.

Colleagues immediately bought the ailing missionary a ticket for the long journey home, accompanied by a nurse, Cynthia Miller. After several days at sea, Lottie's mind seemed to clear. She smiled at her helper and said, "He has come. Jesus is here, now. You can pray that He will fill my heart and stay with me. For when Jesus comes in, He drives out all evil, you know." 16

Alas it was too late, and when the ship docked at Kobe, Japan, on Christmas Eve 1912, the nurse at her bedside said,

"For a long time that morning she had lain very quietly, unconscious. Then she stirred, and seemed to be looking for someone.... The frail, thin hands were clasped together in the Chinese fashion of greeting, and gently unclasped. Over and over there came that look, and the greeting to Chinese friends long since gone on before her—her Chinese women of Penglai and Pingdu, of the villages round about, who she had told of the heavenly home....

And it was thus, with the Chinese handclasp, a smile of greeting and the whisper of a friend's name that Lottie Moon went home." 17

Lottie, who had turned 72 the previous week, had completed her service for God. She would never be lonely again.

Both Christians and unbelievers in Shandong grieved deeply when they heard that their special friend had died. The church leaders at Pingdu simply wrote, "Oh, how she loved us." Stirred by Lottie Moon's example, the believers in Shandong added extra determination to their preaching of the gospel. In the year following her death, 2,358 new converts were baptized in Baptist churches alone.

When news reached America that the veteran missionary had starved to death, there was widespread shock and dismay. Many Christians felt ashamed of their inability or unwillingness to respond to Lottie's appeals for famine relief, and thereafter the annual mission offering in her name was significantly higher.

Lottie Moon's sacrificial life for God helped sow the seeds of revival throughout Pingdu and other parts of Shandong. Although she did not live to see the full fruit of her labors before her death in 1912, by the end of the following decade a tremendous revival was sweeping parts of the province, with the Baptist work at the forefront of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. A Southern Baptist annual report from the early 1930s said, "In the densely populated Pingdu County, there are now villages in which every family has one or more saved persons, and in some villages nearly everyone has accepted the Lord." 18

Today, Pingdu City continues to have a strong and godly Christian presence, and is home to approximately 70,000 Chinese believers.

More than a century after her death, Lottie Moon is still highly regarded as the 'patron saint of Southern Baptist missions'. Generations of church members have grown up knowing her testimony, and a total of $1.5 billion has been raised during the annual offerings, which have typically funded half of the mission budget of the entire denomination.

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book 'Shandong: The Revival Province'. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. Catherine B. Allen, The New Lottie Moon Story (Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1980), p. 84.

2. Ruth A. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1983), p. 237.

3. Janet & Geoff Bende, Lottie Moon: Giving Her All for China (Seattle, WA: YWAM Publishing, 2015), p. 129.

4. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya, pp. 235-6.

5. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya, p. 235.

6. Bende, Lottie Moon, p. 80.

7. Irwin T. Hyatt, Our Ordered Lives Confess: Three Nineteenth-Century American Missionaries in East Shantung (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1976), pp. 49-50.

8. Hyatt, Our Ordered Lives Confess, p. 4.

9. Hyatt, Our Ordered Lives Confess, p. 45.

10. Bende, Lottie Moon, p. 136.

11. Bende, Lottie Moon, p. 138.

12. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya, p. 236.

13. John Woodbridge (ed.), More than Conquerors: Portraits of Believers from all Walks of Life (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1992), p. 60.

14. Bende, Lottie Moon, p. 139.

15. Bende, Lottie Moon, p. 148.

16. Allen, The New Lottie Moon Story, p. 287.

17. William R. Estep, Whole Gospel Whole World: The Foreign Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention 1845-1995 (Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman, 1994), p. 150.

18. Mary K. Crawford, The Shantung Revival (Shanghai: The China Baptist Publication Society, 1933), p. 35.