© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1945 - Eric Liddell

February 21, 1945

Weifang, Shandong

Eric Liddell, Olympic champion and Martyr for Christ.

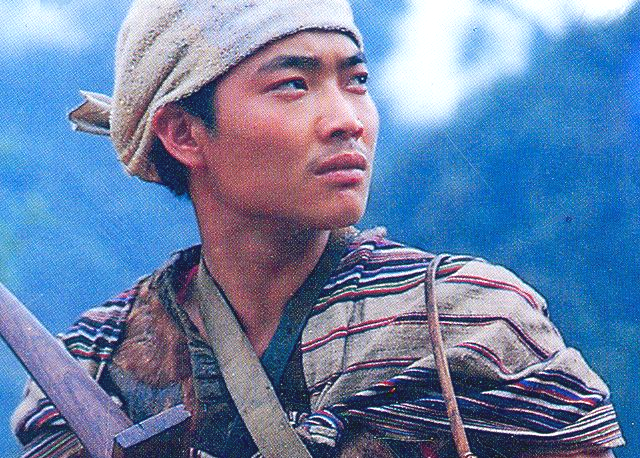

Perhaps the most celebrated China martyr of all time is the Scottish-born Olympic champion, Eric Henry Liddell. Born to missionary parents in Tianjin, China, in 1902, Liddell returned to his homeland as a teenager. Even as a young man his life was marked by a deep faith and consecration to Christ, and he considered all worldly achievements nothing compared to the joy of following God.

At the age of 16, Liddell was already an outstanding athlete. He captained his school cricket team, and possessed an exceptional turn of speed. After entering Edinburgh University in 1920 his sporting career blossomed. He excelled in running events, especially the 100-metre sprint, and his speed enabled him to play international rugby as a wing three-quarter for Scotland. Many athletic victories came Liddell’s way, including a winning run for the British Empire team against the United States.

The 1924 Olympic Games at Paris were looming, and Britain placed her hope in the flying Scot bringing home a gold medal. Sport was not the priority in Liddell’s life, however. In 1923 he joined the Glasgow Students’ Evangelistic Union, and gave himself wholeheartedly to the service of God. Liddell continually asked himself, “Does this path I tread follow the Lord’s will?” His devotion to Christ was complete, and he viewed his ability as a sportsman as a God-given gift by which he could glorify Jesus Christ.

The opportunity came in a unique way during the Olympics. A short time before the Games commenced, Liddell discovered that the heats for the 100-metre sprint were scheduled to be run on a Sunday. The idea of running on the Lord’s Day was abhorrent to him. His withdrawal meant he gave up the almost certain prospect of winning a gold medal in his strongest event. For weeks Eric Liddell’s decision not to run was vehemently criticized by the press in Britain and other parts of the world. Much pressure was brought to bear on him, but nothing would alter his convictions. He later wrote,

“Ask yourself: If I know something to be true, am I prepared to follow it, even though it is contrary to what I want, [or] to what I have personally held to be true? Will I follow it if it means being laughed at, if it means personal financial loss, or some kind of hardship?”[1]

The Olympic 100-meter competition went on without him, and a world that idolizes its sports stars was left reflecting on Eric Liddell’s radical obedience to Jesus Christ. Liddell did compete in the 400-metres, which did not take place on a Sunday. He won a gold medal and set a new world record for the event, and also won a bronze in the 200-metres. The deep love Scotland held for Liddell could be seen at his graduation from university. One account says,

“Scotland loved this young man. He demonstrated on the field just the sort of determination, stamina, and honest excellence that—though perhaps not flashy—the Scots love to see in a native son…. He was literally paraded around the streets of Edinburgh to the adulation of its inhabitants.”[2]

Liddell had only returned to his homeland for his education. All along, his plan was to return to China as soon as he had graduated, and despite his success and popularity, Liddell shocked Scotland by returning to the country of his birth to engage in missionary work in 1925. Everywhere he went for the next few years people flocked to see the Olympic champion. This opened many doors for Liddell to share his faith. Twice during his missionary career he returned to Britain on furlough, and each time the intervening years seemed to have hardly dimmed the appreciation of him as large crowds flocked to his meetings and hung on his every word.

For the first 12 years in China, Eric Liddell taught at the Tianjin Anglo-Chinese College. He was an outstanding teacher and highly respected by all. He taught science and also supervised the school’s sporting activities, but these were not the real reasons he served in Tianjin for so long. His biographer reveals:

“Had that been all, it would not have taken him to China; it would not have kept him on the staff of the Anglo-Chinese college as long as it did; and it would not have justified the writing of this biography…. He was a completely dedicated disciple of Jesus Christ, and a man who could rest short of nothing but the introduction of those brought under his influence to the Saviour and Master who had come to mean so much to him.”[3]

Liddell fell in love and married Florence Mackenzie at Tianjin in 1934. Their relationship produced three beautiful daughters. For years he had faithfully served in the school while countless missionaries passed through from far-flung fields, sharing their victories and struggles. Inwardly Liddell longed to experience such work for himself, and in 1936 he sensed the Holy Spirit was leading him to a new ministry. A vacancy opened at Xiaochang in Shandong Province, but the opportunity coincided with the arrival of the Japanese army. It was considered too dangerous for a family to live in a war zone, so to accept the appointment meant Liddell would have to spend periods of time away from his beloved wife and precious daughters. After wrestling with the decision for a year, Liddell was convinced God was calling him to accept the position.

Shandong was in chaos due to the war. Liddell spent much of his energy rescuing wounded soldiers, knowing that if caught he would be sentenced to death by the Japanese. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the danger for missionaries greatly intensified. Florence and the three girls travelled to safety in Canada, but Eric decided to remain in China. In 1943 he and all his missionary colleagues were arrested and held in a Japanese internment camp at Weifang in Shandong Province.

For Eric Liddell, being imprisoned with more than 2,000 other foreigners (including 327 children) meant an opportunity to teach and encourage the downcast. He threw all his energy into his activities. One account of this time says,

“Of the Protestant missionaries in Weifang, none aroused more admiration and affection than Eric Liddell of the London Missionary Society, and former Olympic hero. On arrival at the camp, the Employment Committee appointed him half-time teacher of Mathematics and Science, and half-time organiser of Athletics. Later he also became the Warden of Blocks 23 and 24. As sports activities decreased with the diminishing vigour of the inmates, Liddell gave more and more of his time to keeping the restless youth in the camp entertained with chess, square dancing and other pastimes.”[4]

After nearly two years of incarceration away from his family, Liddell’s health began to break down. He battled depression, and interpreted the symptoms to mean he was wavering in his faith. He didn’t realize he was suffering from a malignant brain tumour. The end came quickly, and on February 21, 1945, the missionary and Olympic champion went to be with Jesus Christ, just months before the end of the War.

The story of Eric Liddell was celebrated in the award-winning 1981 movie, Chariots of Fire. In 1991 a memorial stone was sent from Scotland to place on Liddell’s unmarked grave in China. After much research the grave was located within the grounds of a school at Weifang in Shandong Province. A service was held at which

“Communist cadres, Asian missionaries, Scottish businessmen from Hong Kong, British diplomats, and family and former friends of Liddell gathered for the ceremony, which included a number by the school band and Scottish bagpipes as well as fond remembrances from Liddell’s friends. At the end of the ceremony a small group of Christians bowed their heads in prayer in front of the memorial stone but were sent away by authorities.”[5]

Although just 42 when he died, millions have been touched by Eric Liddell’s self-sacrificial life and death.

1. Woodbridge, More than Conquerors, 223.

2. Woodbridge, More than Conquerors, 223.

3. D. P. Thomson, Eric H. Liddell: Athlete and Missionary (Crieff, Scotland: Research Unit, 1971).

4. Norman Cliff, Prisoners of the Samurai: Japanese Civilian Camps in China, 1941-1945 (Rainham, Essex: Courtyard Publishers, 1998), 81.

5. “Eric Liddell Memorialized in Weifang,” China News and Church Report (June 1991).