1870s

The Evangelical churches in Shandong had an inauspicious start in the 1860s. The missionary endeavor didn't wane, however, and the following decade saw encouraging growth throughout the province. The church at Yantai (then Chefoo) had been established with just six believers in 1866, but in 1873 alone they admitted 66 new members. In the same year, the church at Jimo added 69 new believers. 1 Despite these encouraging signs, the Chinese congregations struggled to get off the ground, with many of the new believers put out of fellowship, chiefly because of sexual sins and the use of opium.

The missionary enterprise in the province was helped by the passionate appeals for new workers from early missionaries. Isabelle Williamson of Scotland emerged as a new voice as she cried out for women to give their lives for Christ in China. In 1876 she wrote,

"As I stood in the midst of that ancient city [Qingzhou in Shandong], and knew that I was the first woman of a strange race who had ever trod its streets, or walked amid all these altars which had so long smoked with incense to false gods.... I felt I occupied a most solemn position....

I felt my whole being roused in prayer that God would send out more women to teach these millions of immortal beings; and under the same sense of need, I would implore you, O ye Christian women of Scotland, to think of the claims of your sisters in heathen lands. Women are one-half of the human race; there ought therefore to be as many women as men in the field, especially in such countries as China, where only women can properly and powerfully teach women.

Surely God has some chosen vessels among you who will bear His name hither; women with steady zeal and firm nerve, who have already passed through the fire, and are prepared to face trials and death itself, if need be...women who have resolved to spend their lives in the most noble of all services under heaven, so that in that great day the Savior's crown may be adorned with jewels from among the women of this, the most ancient people on earth." 2

Famine Relief

A terrible famine from 1876-1879 caused Richard and other missionaries to focus on relief efforts. Approximately 15 million people starved to death across China, and the situation became so dire that after trying to find sustenance by eating tree bark and weeds, many people resorted to cannibalism. Desperate people tore down their houses and sold the timber at the market for just a few cents in order to buy food. One report grimly recounted, "Girls of six or seven years old were sold for a price ranging from one to two dollars; those from 10 to 12 years sold from three to five dollars." 3

The famine relief work provided a great boost to the Church in Shandong, as tens of thousands of desperate people were helped by the missionaries and their Chinese co-workers. The Presbyterians were also influential in helping thousands of starving people during the famine. They reported, "The little Church grew rapidly. In five years the membership increased from 108 to 1,000." 4

Over time the work of the gospel in Shandong spread exponentially. Schools, orphanages, hospitals and medical clinics were opened to reach and train the people, while Timothy Richard and his co-workers strongly believed the local Chinese churches should stand on their own feet with as little foreign help as possible. This insistence on self-support caused the Shandong Church to grow in strength and commitment. From the beginning,

"The principle was adopted of doing nothing for the Church which it could and ought to do for itself.... In fixing the salaries of the pastors the desire was not to make them rich men but respected men, and it was felt that the pay of the native schoolmaster was a very good guide. By the plan adopted the pastors live in their own homes, attend to their farms in the busy harvest season and give about nine months of their time entirely to the Church." 5

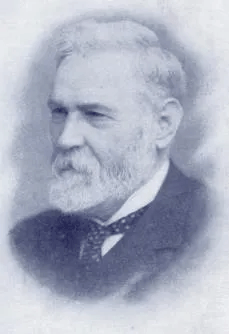

Timothy Richard later in life.

After cancer claimed his beloved wife in 1903, Timothy Richard continued to serve his Master throughout China for many years, until poor health forced him to leave in 1916, after 46 years of sterling service. The latter years of Richard's life proved difficult, and a growing number of missionaries opposed his methods. They saw little value in ministry that focused on helping people's bodies instead of their souls, and Richard's strategy of reaching China through education rather than the direct proclamation of the gospel attracted criticism that he was a liberal who propagated a social gospel.

Timothy Richard's decades of exertion in China had drained his stamina, and the great missionary died in April 1919, having led a full and fruitful life for the kingdom of God. The esteemed Church historian Kenneth Scott Latourette did not hesitate to describe him as "one of the greatest missionaries of any branch of the Church," while long before his death, China had bestowed great honor on Richard, even conferring on him the highest rank of Mandarin. A contemporary missionary, William Soothill, wrote, "Had he died in China, his funeral would have been the greatest of any foreigner who has ever lived in that land." 6

Stunning Growth in Shandong

By 1879 the total number of foreign missionaries in Shandong numbered 28, accompanied by 25 Chinese co-workers. One survey found, "Fourteen churches have been organized, and there are 734 converts in communion. There are 26 schools, containing 534 students. The progress therefore is remarkably good considering the shortness of the time since the work commenced."

As the decade had progressed, the number of Chinese believers in Shandong steadily increased. Two missionaries, Owen and Gilmour, baptized 110 converts in November 1877, and an additional 200 people declared their desire to learn more of the Christian faith. The following March the missionary duo visited Zhanhua, where they baptized another 200 new believers in Christ Jesus. The gospel advanced so quickly that in July 1878 Owen and Gilmour reported, "The movement has been proceeding with great rapidity. There are now 1,600 persons under instruction and of these 420 are reported as suitable for baptism. The converts belong to 20 or 30 towns and villages, and to persons of all grades in society. The movement has extended to four neighboring districts, and there is no sign of any check to its progress at present....

One of the most prominent features of the movement is regular family worship and the use of the Lord's Prayer, even in houses where the members may not be baptized. Remarkable willingness has been shown to engage in this outward act of Christian profession."

The missionaries sought out those who were interested in the gospel, and didn't waste their time trying to convince those who were hostile to their message. John Nevius remarked in 1880, "During the last four years, above 50 mission out-stations have been established in central Shandong, mostly in the district cities of Qingzhou. They have connected with them about 500 church members, and nearly as many more applicants for baptism."

Meanwhile the Presbyterian missionary Hunter Corbett reported from eastern Shandong:

"In certain districts the gospel has been preached and books left in every town and village. In a few places the open opposition was such that it seemed wisest to lose no time in passing to the next village. The intense indifference to the truth in other places did not tend to cheer the heart of the laborers. In some places, however, many men and women were not only willing, but anxious to hear.

Not a few who received copies of the Gospels and Christian books in the early part of the year studied them, so that they are now able to give a clear outline of the life and work of Christ. A number desire baptism. Little groups in different places meet regularly on the Sabbath for worship and the study of God's Word....

During the year [1879], 82 were received into the Church on profession of faith. There are now 613 communicants on our Church roll. There were less than 20 when the Presbytery was organized 14 years ago."

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book 'Shandong: The Revival Province'. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. Heeren, On the Shantung Front, p. 59.

2. Missionary Record of the United Presbyterian Church (January 1876).

3. Heeren, On the Shantung Front, p. 71.

4. American Presbyterian Mission, The China Mission Hand-Book (Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press, 1879), p. 42.

5. Pat Barr, To China with Love: The Lives and Times of Protestant Missionaries in China 1860-1900 (London: Secker and Warburg, 1972), pp. 44-5.

6. Evans, Timothy Richard, p. 157.

7. China's Millions (January 1879), p. 8.

8. "Christian Movement in the Province of Shantung," Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (August 1878), p. 282.

9. John L. Nevius, "Mission Work in Central Shantung," Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (October 1880), p. 357.

10. Hunter Corbett, "Shantung Presbytery," Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (January 1880), pp. 72-3.