The Nosu (1940s)

A group of Nosu Christian women in 1914.

The Nosu people are thought to have lived in the rugged mountains of western Guizhou for at least 2,000 years. Their origins are uncertain, but their language places them as part of the great Tibeto-Burman race. Like many other native peoples in China and around the world, the Nosu possess an ancient flood legend, which has been passed down for countless generations. The Nosu account says:

"A certain man had three sons. He received warning that a flood was about to come upon the earth, and the family discussed how they should save themselves when this calamity came upon them. One suggested an iron cupboard, another a stone one, but the suggestion that they should make a cupboard of wood and store it with food was acted upon."

Although today they are considered just one part of the multi-faceted and artificial 'Yi' minority group created by the Chinese government, for centuries the Nosu people in western Guizhou and neighboring provinces were renowned for their fierce independence. The Han commonly called them derogatory names, and even after the Chinese empire had expanded its influence, the terrified Chinese generally refused to enter Nosu territory, which they considered off-limits.

Missionary Samuel Pollard described some of the conflicts between the Chinese and the Nosu: "After a fight, the warriors who are killed on either side are opened up and their hearts removed, perhaps also their tongues, and these are cooked and eaten. It is supposed to be a way of inheriting the courage and valor of the deceased."

For many generations the Nosu captured slaves, and did not discriminate between races. They took Chinese slaves, forced thousands of Miao and other tribesmen to serve them, and they didn't hesitate to even take other Nosu captive to work their fields. During the Second World War, some of the British and American pilots who flew supplies from Burma into China were forced to parachute out of their airplanes over the Nosu region and were never heard from again. Rumors spread that they too were taken into slavery by the Nosu who dwell in the nearly impenetrable Daliangshan ('Great Cold Mountains') in neighboring Sichuan Province.

While Nosu areas in Sichuan were considered too dangerous to visit until recent decades, the government was able to subdue the Nosu in Guizhou more easily. In 1727 the Emperor Yang Cheng sent troops into the Nosu areas and slaughtered tens of thousands of people. As a result, great numbers of Nosu migrated away from their traditional homeland.

Conditions among the Nosu were reportedly so dire and unhygienic in the 1900s that their very survival was questioned. One writer noted, "The unsanitary conditions in which they live—the water they drink is often drawn from stagnant pools fouled by sheep and cattle—and their riotous indulgence in whisky, opium, and other vices, sufficiently account for this.... They are burdened with the thought that their doom as a race is sealed."

Although Christianity among the A-Hmao and other Miao tribes had flourished in Guizhou since the early twentieth century, the gospel had barely touched the more than 70 other people groups scattered throughout the province.

Divisions of Nosu

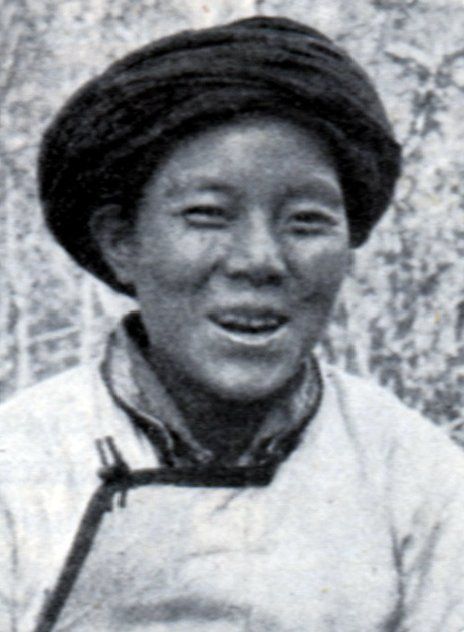

A White Nosu Christian woman.

The Nosu were traditionally divided into two main classes of people. 'Black Nosu' were the slave owners who possessed vast tracts of land in west and northwest Guizhou and across the borders in Sichuan and Yunnan.

The 'White Nosu' were the serf class with no rights whatsoever. For centuries they were enslaved and mistreated by the Black Nosu. Some were forced into slavery because of debt and economic necessity, but many others were captured by fearsome raiding parties. Sweeping into villages on horseback, the Black Nosu looted and burned communities to the ground, taking away whomever they wished. The plight of the slaves was pitiable. Most were chained up and forced to work like pack animals, and many quickly perished.

The Nosu penchant for taking people by force also manifested itself in their notorious tradition of 'bride snatching,' when groups of Nosu men descended on a village and carried off a pretty girl, who would be forced to marry one of their number. The grieving parents would often never see the girl again, leaving them heartbroken for the rest of their lives.

There are four main Nosu groups in Guizhou today, each speaking its own language. The largest group, numbering more than 200,000 people, has been labelled the Panxian Nosu after the county they predominantly occupy. The three other Nosu groups in Guizhou are the Wusa Nosu, the Shuixi Nosu, and a small subgroup of about 5,000 Tushu people, who are the descendants of slaves.

After the fire of the gospel blazed through A-Hmao communities in the early 1900s, the attention of some missionaries turned to the Nosu further north. Unsurprisingly, the White Nosu slaves were far more receptive to the offer of salvation, while the Black Nosu slave owners were resistant. They were concerned that a shift to Christianity would usurp their dominance over the people of the region.

When the missionaries began to reach out to the Nosu with the gospel they met stiff opposition. Samuel Pollard wrote in 1905:

"We crossed the sides of a big mountain...and finally arrived at the fort of a Nosu landlord called Loh-chig. He received us kindly and we stayed there the night.... He told us straight he would rather lose his head than become a Christian. He refused all gifts of books, disputed all we said, and denied all our attempts to win him over. He stuck up strongly for his religion and defended the worship of idols with great zest."

Undeterred, Pollard and his colleagues continued to sow the seed of the gospel. The fire of the Holy Spirit began to burn among the Nosu living on the Yunnan side of the border, and soon spread to Weining County in Guizhou.

By 1907, not only had White Nosu slaves turned to Christ, but even some Black Nosu had bowed their knees to the King of Kings. Pollard rejoiced: "A blind Nosu here who has become a Christian has released all his slaves and burnt the papers that bound them to him. He told them that they could remain as tenants. He has persuaded his nephew to do the same and other families have followed suit. Some he has persuaded to destroy their idols."

It was Pollard who first suggested that where Miao and Nosu people lived alongside each other, the believers should meet together on Sundays and worship in whatever language was common to each group. The two peoples had long kept their distance, but now the love of Jesus Christ was breaking down the dividing walls of hostility and a remnant of redeemed Nosu people was emerging. In a diary entry dated July 2, 1910, Pollard noted: "Today I saw a miracle. At this lonely place the church was full of Nosu, and at their request Chang Yuehan (John Chang) was preaching to them. The proud Nosu listened to one of their Miao serfs."

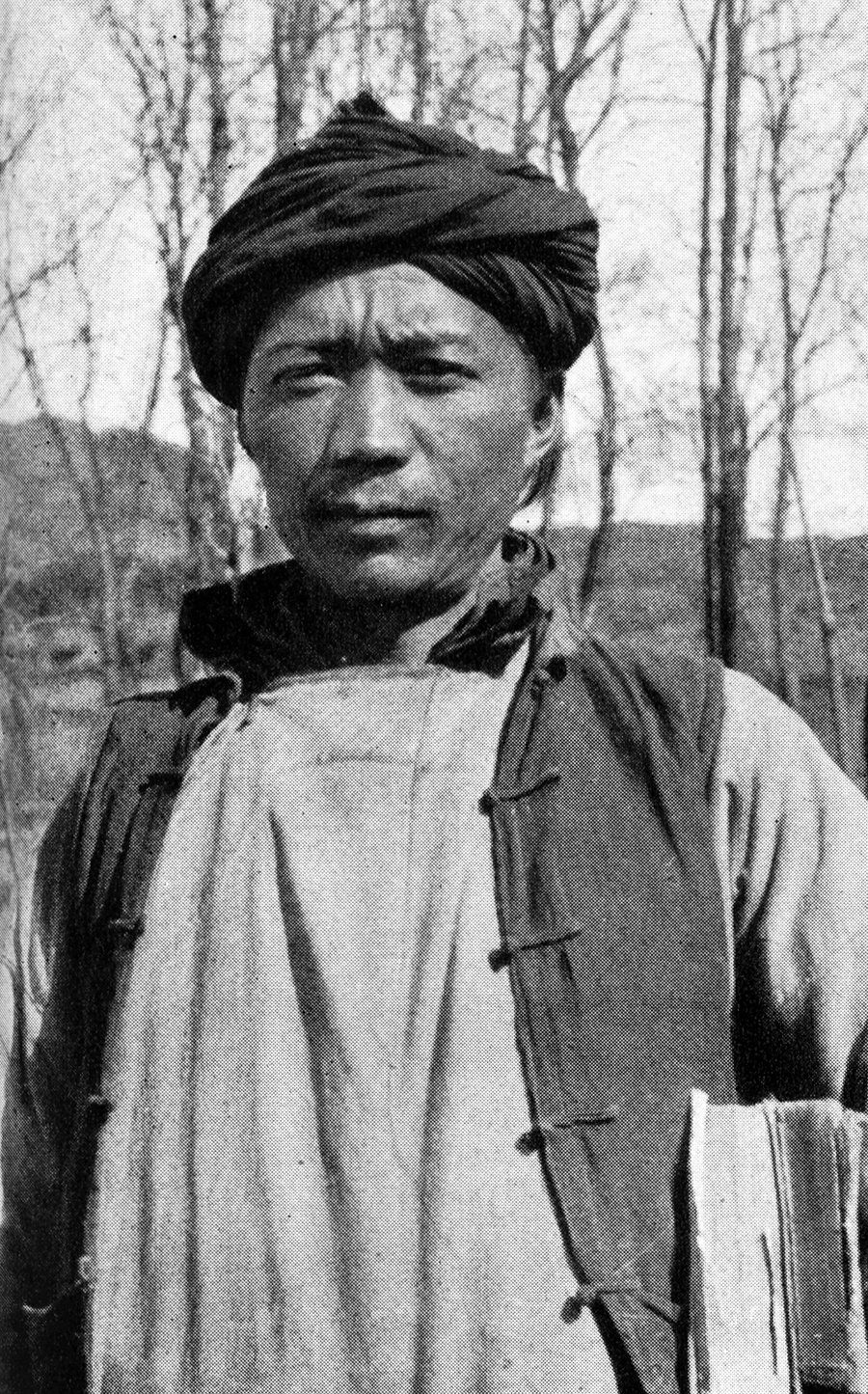

A White Nosu evangelist.

Although James Adam's work had focused on the A-Hmao and other Miao tribes, in 1911 he also wrote about his first Nosu converts. After a journey through northwest Guizhou, Adam reported:

"We rejoiced to see the way in which the gospel is taking hold of the poor despised White Nosu (who are mostly slaves). There is a fine work of grace going on among this class of Nosu. I specifically ask prayer for them. They are all exceedingly poor, but oh, so very earnest in learning the gospel. A dear White Nosu man named Joseph is the leader, and the Lord's chosen vessel for pouring blessing upon the very lowly folk. He knows the Scriptures well, and is always ready to answer the questions put by the preacher in the meetings. The Master has blessed our brother and is making him a big blessing to others."

A group of Nosu men followed Adam back to his home in Anshun, so they could learn more about Christianity. The hope, as with the A-Hmao several years earlier, was that these earnest seekers would return home as born-again Christians, becoming the vessels for the gospel to reach thousands of their fellow tribesmen and women.

In the following years a significant number of White Nosu did become followers of Jesus, but the Black Nosu rose up in opposition, and put some of the new believers to death. James Adam realized that as long as the new believers remained enslaved, the Christian faith would struggle to survive among them. After prayer, he came up with a strategy to help the White Nosu and Miao Christians purchase small plots of land from their Black Nosu oppressors. This altered the course of the believers' lives. Adam listed the benefits of this initiative:

"No more paying of exorbitant rents. No more going off in daily gangs to work the chieftain's lands without receiving either pay for work done, or food while laboring for a cruel, hard landlord. No more paying of silver, or having animals taken whenever the landlord fancied he required use of both. No more imprisonments in dark dungeons, with heavy chains weighing the sufferers down, because the wicked landlord could find neither the needed silver nor the coveted animals in the poor tenant's home."

The Gospel Takes Root

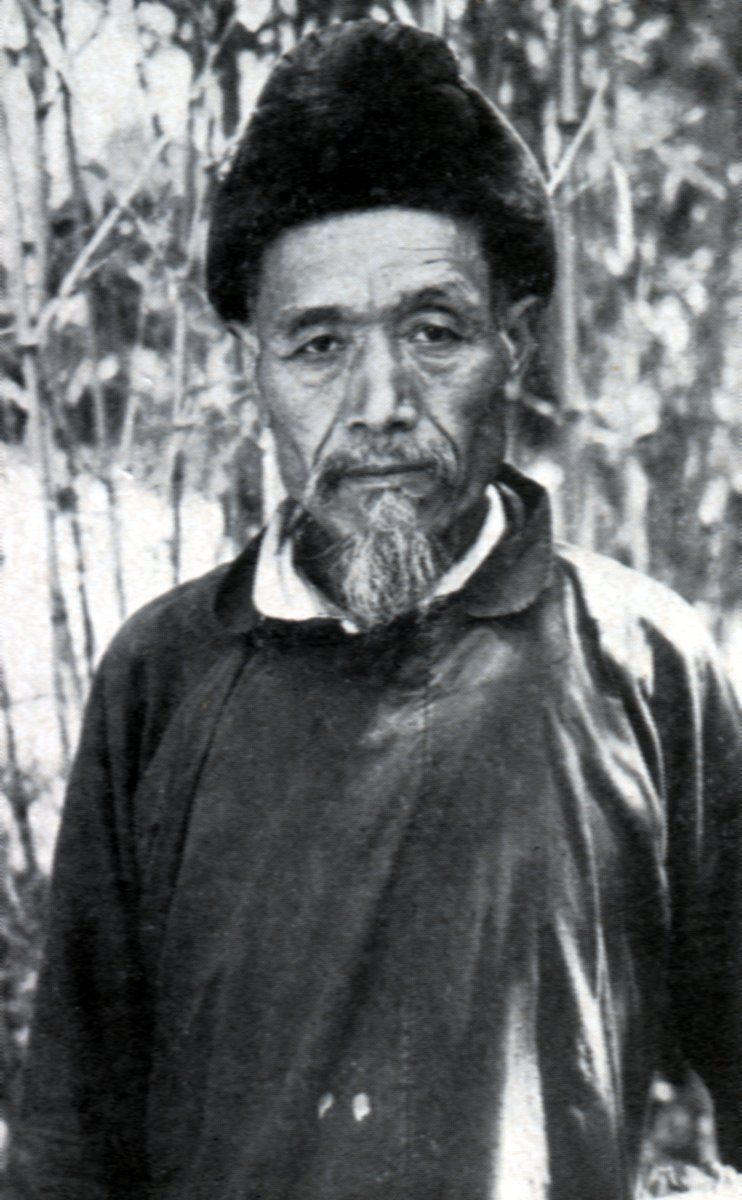

Chiopa, a Black Nosu church leader.

When missionary Isaac Page moved into the Nosu area, he employed a dual strategy of reaching both the Nosu and their Miao neighbors. Page was encouraged by the progress and reported in 1918:

"The work is opening up on all sides, among both Miao and Nosu. Crowds of the latter are coming to enquire, and we thank God who enabled us to make our home among these tribespeople. Any inconvenience that living in such a wild place entails soon drops out of sight when we see souls pressing into the kingdom. In all, 134 have been received into the church at this time, and many more are hoping to be so."

In the early 1920s, a mission survey rejoiced at the progress that was taking place among the Nosu people. In describing how many had come to faith in the living God, the report noted:

"The Holy Spirit has given gifts to the Church in Guizhou even as He did in the early days. These men, with little education, have proved themselves equal to the task, and the Church has been built up in a very real way.... Every Christian is a potential evangelist, and the tribespeople, almost everywhere, do all the evangelizing, the missionary following in their wake to consolidate what has been done....

During the last year more than 1,000 families have come to us as enquirers, nearly all of whom belong to the White Nosu, or Tushu. Their interest in the gospel had been awakened through a number of our voluntary helpers, as well as through the work of our A-Hmao evangelists.

One man of this Tushu tribe—a farmer and who does Christian work voluntarily—is arranging to visit all the villages of his people where there has been any interest manifested, and intends to spend three days in each place and give what help he can to these new enquirers."

The work among the Nosu continued to expand, and many people repented of their sins and put their trust in Jesus as the gospel spread from village to village throughout the rugged hills and deep valleys of northwest Guizhou.

In His wisdom, God primarily chose the Miao Christians to reach the Nosu. Despite looking down on the A-Hmao and other Miao tribes for centuries, the dramatic change that had come into their communities after they embraced Christ did not go unnoticed. Many Nosu wanted to experience the same peace and joy as their former slaves.

One factor holding back the growth of the Nosu churches in Guizhou at this time was the absence of Scripture in their language. Portions of the Bible had been translated into a special Nosu script in 1913, but these were for use among the Nosu in Sichuan and Yunnan. The Nosu in Guizhou spoke a different language and the script was never taught in the province.

An outdoor service of White Nosu Christians in 1937, led by a Black Nosu preacher.

The Nosu Today

Although the size of the Church among the Nosu in Guizhou has always paled in comparison to the massive revival among the neighboring Miao tribes, God has nonetheless done a powerful work among the Nosu. Because of government persecutions against Christianity in the 1960s and 1970s, many Nosu churches in Weining County went underground, where believers met secretly in small prayer and Bible study groups. In 1988, when national policies were relaxed, 15 Nosu churches reopened in Weining.

The congregations continued to grow, with one researcher noting in the late 1990s: "In northwest Guizhou the concentration of Christians among the minorities is sometimes very high. For instance, Geda village in Hezhang has 65 Nosu families, of which 57 are Christian."

The Nosu believers have been called to endure many harsh trials and persecutions over the decades, but God preserved a faithful remnant for His glory, and today many strong churches exist among the Nosu of northwest Guizhou.

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book 'Guizhou: The Precious Province'. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.