Half a century after the first Evangelical missionaries arrived, the CIM had done a sterling job to the best of their God-given abilities, but Guizhou was unique among the provinces of China in that a single mission society almost completely dominated the work in an entire province, with only a handful of Methodist missionaries in northwest Guizhou adding variety to the mix.

Ironically, the tremendous revival among the A-Hmao and other tribes appears to have negatively affected the work in the rest of the province in two ways. First, other Evangelicals read the stirring accounts of thousands of baptisms and assumed the CIM were well-placed to extend their work. Second, the CIM focused most of their missionaries and resources among those tribes, to the neglect of dozens of other unreached ethnic groups and the millions of Han Chinese in the province.

The lack of workers in a territory as large and populous as Guizhou was startling, with vast areas going without any gospel witness. The eastern and southern parts of the province were particularly neglected, to the point that a nationwide survey in 1922 expressed alarm at the lack of activity:

"Guizhou averages four missionaries per 1,000,000 inhabitants, and five per 1,000 communicants. When considered, therefore, solely from the standpoint of missionary occupation, Guizhou is the most poorly occupied province in China, the average for the entire country being almost four times better, or 15 missionaries per 1,000,000 population, and 19 per 1,000 communicants.... Over one half of the province still remains unclaimed, although it is occasionally visited by colporteurs, Chinese evangelists, or missionaries."

Although the reasons for such slow progress in the Guizhou missionary endeavor remain unclear, some reports suggest disunity and frustration, even among the two groups that were laboring in the province. The same survey noted:

"The United Methodist Church reports a meeting of its representatives with representatives of the CIM, at which the question of respective fields in western Guizhou was considered. The results of this meeting have not been satisfactory, and are, therefore, not acceptable to all concerned.... Lack of funds, resulting in inadequacy of staff both foreign and native, is mentioned by all correspondents as the first and chief reason for the present inadequacy of Christian occupation."

The contrast between Guizhou and neighboring provinces was stark. To the south in Guangxi—a province that shares many similarities—the first Evangelical missionaries arrived only in 1893, 16 years later than in Guizhou. The Christian and Missionary Alliance emerged as the prominent organization serving in Guangxi, but by the 1920s a dozen other mission societies were sharing the burden and helping spread the gospel. The CIM Superintendent for Guizhou, Jack Robinson, lamented the lack of laborers in his province:

"We have in Guizhou working among the Chinese as distinct from the tribespeople, 44 foreign missionaries, and only 10 Chinese workers. That is, over four missionaries have to share one worker between them. In Guangxi, the Christian and Missionary Alliance have about 20 workers and about 140 Chinese helpers, or seven Chinese workers to each missionary.... Thus for Guizhou to have the same ratio of Chinese workers to missionaries as they have in Guangxi we need 300 trained Chinese workers."

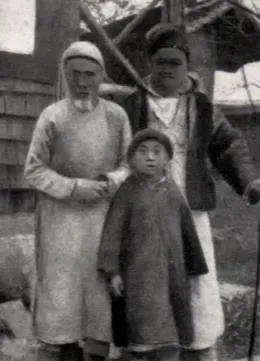

Seventh-Day Adventist missionaries Claude and Irene Miller in A-Hmao clothes, 1920s.

The CIM were quick to oppose the Seventh-Day Adventists when they tried to gain a foothold in Guizhou. The CIM strongly opposed their doctrine and were grieved by the spiritual condition of their members. Harry Taylor wrote this scathing assessment from Guiyang:

"The Seventh-Day Adventists are few in numbers. In all places where there are members they are using money and influence to get believers to go to them, and for the last two or three years have been a disturbing influence in our district. They accept all excommunicated members and enquirers after the briefest instruction about keeping Saturday and not eating pork, and they give them status as church members. They then use their knowledge of the Christians to seek out all to entice them away. Their members smoke and deal in the soul-destroying opium, and are not rebuked for it."

Whether the CIM consciously or sub-consciously blocked other mission groups from working in Guizhou is uncertain, but the harvest in most other Chinese provinces by this time was being gathered by numerous mission groups including Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Pentecostals, Anglicans and others. In Guizhou, however, the CIM continued to almost exclusively dominate the Evangelical landscape.

The Catholics, on the other hand, had few restrictions on their work and their numbers increased sharply throughout the decade. In the early 1920s, Catholics in Guizhou outnumbered Evangelicals by almost a 4:1 ratio, and while many Evangelical churches were mired in a state of inertia, the Catholics surged ahead and nearly doubled their church membership by the end of the decade. Most of their work was concentrated in and around the capital city Guiyang, and in the southern districts of Guizhou.