© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1927 - 600 Haifeng Catholics

November 20, 1927

Haifeng, Guangdong

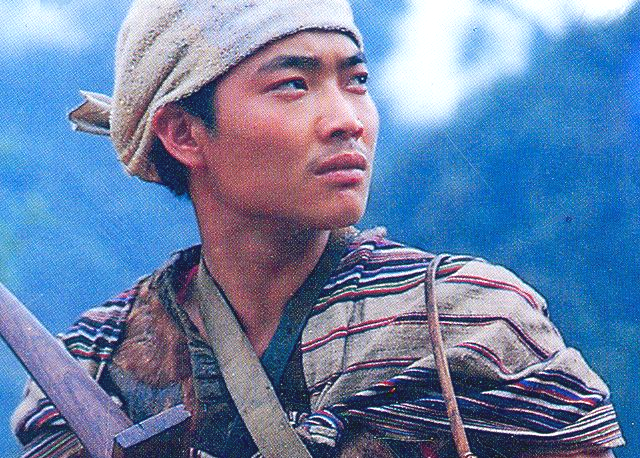

A 1920s Chinese Catholic village and missionary in Guangdong Province.

Haifeng is today a growing industrial city of approximately 700,000 people, located on the South China Sea in Guangdong Province. In 1927, more than 600 Christians were slaughtered by Communist forces in this sleepy corner of China. For centuries Haifeng had been considered a nest of pirates and rebels. When the Communists arrived they found many people opposed to their message and aims. In response, they launched a bloody insurrection between 1925 and 1928, resulting in thousands of deaths. The London Times of February 13, 1928, reported on the massacre of thousands of people in Haifeng with these words:

“The details…contain particulars which would be too painful to repeat…. It is perhaps enough to say that conditions at Lingchi, famous for deaths by the thousand, might be regarded now as comparatively mild, with women seeing their babies massacred before themselves suffering death, and corpses rotting in the streets. The Communist motto is ‘Better 10,000 innocent victims than that one anti-Communist escape.’ This principle they are carrying out with a ferocity which has long degenerated to mere blood lust.”[1]

The Catholic churches in Haifeng County had been administratively included under the Hong Kong Diocese since 1860. Two Italian priests (Lawrence Bianchi and Michael Robba) stationed in Haifeng were in constant contact with their superiors in Hong Kong, updating them with the emergency that started in late 1927. Suddenly, just before Christmas, all news from the pair ceased. They had been arrested along with a number of Chinese Catholics, and plans were underway for a mass public execution. A Chinese believer, who owned a small boat, immediately commenced the 200-mile journey to Hong Kong in order to warn the Catholic Bishop of the dire developments. This brave messenger arrived on Christmas Eve.

Meanwhile, in the prison at Shanwei, Christmas Day dawned with the priests and nuns convinced it would be their last in this world. The Communists had organized a large public rally against them. Lawrence Bianchi recalled how,

“From early morning, people poured into the city from nearby villages to participate in the demonstration against us. From our windows we could read the signs prepared for the parade: ‘Death to the Christian foreign devils’; ‘Religion is the opium of the people, down with the Catholic priests’ …. The most crucial moment was at about noon when we saw some of our parishioners, including a young girl, led to the execution place. All of them were shot by the soldiers. I believed they died real martyrs’ deaths and that one day they will be recognized by the church as martyrs.”[2]

Thirteen believers were killed on Christmas Day, 1927, in Shanwei, with many more executed in the other villages of Haifeng County.

When the messenger finally reached his destination with the sombre news, the Catholic Bishop of Hong Kong, Henry Valtorta, was faced with a life-or-death decision. He decided to launch a bold and courageous bid to rescue his imprisoned brethren. He immediately went to consult Sir Cecil Clement, the British Governor of Hong Kong, and a plan was concocted. On December 27th a British destroyer steamed into the harbour of Shanwei, the port of Haifeng County. The bishop had agreed to the plan only on condition that no force would be used in the rescue operation. Valtorta was on board, standing next to the English captain. A small group of British soldiers and the bishop boarded a sloop and made their way into the town in search of the captive Catholics. Valtorta had hoped that the presence of the destroyer would cause panic among the Communist soldiers who controlled the city, and he was right. Two hours later “the sloop returned to the destroyer carrying two Italian priests, two Chinese priests and four Chinese sisters. They had been scheduled for execution by the communist rebels that very day.”[3]

The remarkable rescue of these eight believers was a small glimmer of good news in the midst of an orgy of demonic slaughter in Haifeng. In 1935, Catholic missionary Nicholas Meastrini returned to the area with Bianchi and Robba, the two priests who had been rescued in 1927. When they visited the village of Ciap-gin, a tearful Bianchi provided more details about the horrible massacre that occurred there eight years previously. Many of the people in Ciap-gin were Catholics. They wanted nothing to do with Communism and resisted when a small troop of soldiers threatened them. The Reds were unable to penetrate the wall around the village and retreated back to the town. A few days later, however,

“Three hundred Red soldiers and a motley crowd of farmers well-armed with hatchets, crowbars and other implements for pillaging besieged it. Resistance lasted only a few days and our Father Francis Wong, at the risk of his own life, tried to mediate an honourable surrender. But all was in vain. On November 20, 1927, the Communists invaded the village, massacred more than six hundred people, inserted iron wires through the ears and noses of the village leaders and dragged them through the streets of the city until they bled to death. The rampaging crowd threw others alive into a pool and when they surfaced shot them to death. Many more were bound together, doused with gasoline and burned alive, amid shouts of joy from the spectators.”[4]

Heaven was richer for the influx of so many blood-bought believers, but China was the poorer for once again slaughtering those who had been sent to bring them the message of Christ’s salvation.

1. London Times (February 13, 1928).

2. Rev. Nicholas Maestrini, My Twenty Years With the Chinese: Laughter and Tears 1931-1951 (Avon, NJ: Magnificat Press, 1990), 148.

3. Maestrini, My Twenty Years With the Chinese, 144.

4. Maestrini, My Twenty Years With the Chinese, 146.