© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's epic 656-page China’s Book of Martyrs, which profiles more than 1,000 Christian martyrs in China since AD 845, accompanied by over 500 photos. You can order this or many other China books and e-books here.

1784 - The Great Religious Incident

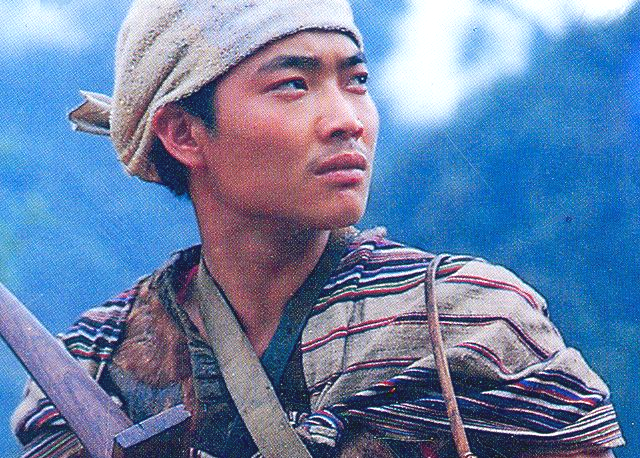

One of the cruel ways 18th-century Chinese believers were tortured by their captors.

The year of 1784 witnessed the start of a particularly severe persecution against Christians.[I] It is remembered in Chinese history as Da Jiao’an (‘The Great Religious Incident.’) Muslim revolts in Shaanxi had made the government suspicious of all religious activity. In the summer four Italian Franciscans were betrayed on their way to Shaanxi and handed over to the authorities. The Qianlong Emperor ordered

“…the destruction of all churches, the arrest of European and Chinese priests, the punishment of the officials who had permitted the foreigners to penetrate the country, and the renunciation by Christians of their faith. As a result of the edict sixteen European and ten Chinese priests were apprehended in various parts of the Empire…and were conveyed to Beijing and cast into prison.”[II]

The prisoners were subjected to terrible conditions and harsh treatment. A record of the way the trial was carried out gives a glimpse into the kind of suffering they were forced to endure…

“The prisoners were led before the tribunal, and while being questioned, were chained with three chains, on hands, feet, and around the neck, and had to kneel bareheaded on the floor before the officials…. After the emperor had ratified the sentence, it was carried out at once; in cases of capital punishment only, a waiting period was provided for those cases where immediate execution was not expressly called for.”[III]

The government had planned to postpone the trials until all the arrested Christians had arrived in the capital from the various provinces where they had been apprehended,

“…but by Chinese New Year’s the number of Catholics crowding the prisons had become so large that it was deemed advisable to dispose of a first group of prisoners. Thus, soon after the New Year’s celebration which, in this year, was especially festive because of the 50th anniversary of the reign of the emperor and of its being his 75th birthday, the first 53 Catholics were singled out to receive their sentences.”[IV]

Before the trial was completed ten out of the 53 prisoners died from the filthy conditions and lack of food. Thirty Chinese catechists (those who instructed and prepared new converts for baptism) were sentenced to perpetual slavery, and banished beyond the Great Wall to the inhospitable realms of the barbarian tribes. Six European and four Chinese priests died in prison, including the 33-year-old Atto Biagini who perished after suffering “persistent attacks of dysentery which had reduced him to skin and bones.”[V] Biagini was a Franciscan from Pistoia, Italy. After a stint in Syria and Egypt, he was sent to China in 1782. During the persecution of 1785 he was captured in Shandong Province and taken to Beijing, where he died in prison on July 25, 1785.

Frenchman Jean-Baptiste de la Roche died while he was being transported to the capital. An ex-Jesuit priest, de la Roche was 80-years-old and had been blind for several years. When soldiers arrested him at his mission, de la Roche “was put in chains and led away to be questioned, but on the following day he was found dead. The Christians secured his body and buried him in Chayuangou.”[VI]

The names of some of the Chinese believers who died in prison were John Ai, Du Xingzhi, Liu Huichuan, Long Zhengyou, Han Si, Liu Yichang, Liu Shiqi, and Tian Kang. Du Xingzhi had been described as “one of the outstanding members of the Catholic Church in Shaanxi.”[VII]

The second set of trials concluded without the passing of any death sentences, but the European missionaries Giovanni da Sassari, Giuseppe Mattei, Giovanni Battista da Mandello, Antonio Luigi Landi, Giacomo Ferretti, and Manuel Gonsalvez were sent to prison for the rest of their lives. These men were new arrivals in China. After risking their lives on the long sea journey from Europe to the Orient, they were arrested while on their way from Macau to their appointed mission in north China. They faced the rest of their lives rotting in a Chinese prison, chained and manacled to the wall. It is presumed they all perished while in custody.

Another priest named Cajetan Xu Gaidanuo was born in 1748 at Ganzhou in Gansu Province. As a young man he had pursued medical and literary studies, and after embracing Christianity he travelled to Europe to study for the priesthood. His relatives back in China, upset at the length of his absence, compelled him to return to China before he had completed his studies. Bishop Sacconi ordained Xu a priest in 1782. He was arrested during the 1785 persecution and exiled to Ili, where he died around the turn of the century after 15 years of slavery.

Ten Chinese laymen, who had assisted the missionaries in their travels, received the same sentence. Their names were Jiao Chengang, Qin Lu, Xie Boduolu, Liu Shengchuan, Zhou Cheng, Xu Zongfu, Han Fengcai, Fan Tianbao, Ge San, and Wei Si. These men were never heard from again, and it is believed they died in slavery. Another Catholic, Zhang Yongxin had voluntarily surrendered to the authorities. As a ‘reward’ for his surrender, Zhang’s sentence was reduced from lifelong slavery in Ili to one of lifelong slavery in Urumqi!

Hundreds of other Christians received beatings, torture, banishment, and a range of other severe punishments. One source says,

“Three others, found guilty of having indirectly helped the foreigners, were sentenced to 100 blows with the flat bamboo plus three years’ banishment; eight others who had failed to denounce the presence of missionaries or concealed their fellow-Christians when pursued by the government, were to receive 100 blows, were to wear the Cangue for two months and were to receive afterwards 40 additional blows; 12 others were to be punished with 100 blows only.”[VIII]

Graves of Catholic missionaries at Beijing’s Five Pagoda Monastery.

As their investigations continued the government became aware that dozens more missionaries were in China than they had originally thought. Reports came in from each province telling of numbers of foreigners arrested. Most had been living and ministering secretly in China with even local officials unaware of their existence. On April 11, 1785, the delegation from Shandong Province arrived in the capital with five Catholics in chains. Crescenziano Cavalli, Adrian Zhu Xingyi, Li Song, and Shao Heng were taken on the arduous journey into exile at Ili and never heard of again. Zhu Xingyi was a native of Fujian, and an alumnus of the Ayutthaya General College of the Missions Etrangères de Paris (Paris Foreign Missionary Society) at Siam (now Thailand). He died a short time after arriving in Ili.

Sichuan Province yielded four missionaries, who arrived in chains at Beijing on April 28, 1785. Two French priests, Devaut and Delpon, died before their sentences were announced.[IX] In late 1785 the remaining Franciscan missionaries were released from prison on condition that they leave China.[X] Most decided to leave, with the plan of returning to China as soon as possible. Two of the French missionaries secretly returned to Sichuan in 1789.

Dominic Liu Duoming’e was a native of Lintong County in Shaanxi Province. In 1762 he sailed for Europe, where he studied for the priesthood at the Chinese College in Naples, Italy. After being away for 15 years he returned to Shaanxi and became a missionary to Gansu Province, where many Muslims and Tibetans lived. Dominic Liu Duoming’e was arrested in a village near Ganzhou. He was taken to Beijing and sentenced to life in exile in Ili, where he died on March 30, 1788.

When the dust settled on the persecution of 1784-85, hundreds of believers in Christ had been martyred or condemned to slavery for the rest of their lives. The trials in Beijing had only featured those foreign missionaries and the Chinese who had helped them. More severe punishment was metered out to Chinese believers in the provinces.

The Catholic Church in China flourished in the years following the Great Religious Incident. The threat of severe persecution had done nothing to damper the growth of Christianity. In the three southwest provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou 469 adult baptisms were recorded in 1786, and 1,508 in 1792.[XI] As G. B. Marchini wrote to the Congregation of Propaganda in Rome:

“Many intrepidly confessed their Faith in the midst of their torments, and they showed a fortitude and constancy equal to the Christians of the primitive Church. Among others, there is the story of an old Christian who, when cruelly beaten and tortured, encouraged his torturers to be even harsher with him, because he esteemed himself fortunate that after so many years of his life he had an opportunity to suffer something for the love of his Redeemer.”[XII]

I See Jean-Joseph Descourvières, “Relatio Persecutionis excitatae in Sinis anon 1784 et continuatae anno 1785,” Apostolicum (Tsinanfu: no.5, 1934), 383-386; and (no.6, 1935), 34-40; and Jean-Joseph Descourvières & Claude François Létondal, “Histoire Abrégée de la Persecution Excite en Chine Contre la Religion Chrétienne, en 1784 et 1785, Extradite de Plusieurs Letters éscrites in 1785 et 1786.” Nouvelles des Missions Orientales (Paris: Vol.II, 1787), 4-83.

II Latourette, A History of Christian Missions in China, 172.

III Willeke, Imperial Government and Catholic Missions in China, 138-139.

IV Willeke, Imperial Government and Catholic Missions in China, 140.

V Willeke, Imperial Government and Catholic Missions in China, 148.

VI Willeke, Imperial Government and Catholic Missions in China, 122-123.

VII Willeke, Imperial Government and Catholic Missions in China, 80, f.n.21.

VIII Willeke, Imperial Government and Catholic Missions in China, 144.

IX See the ‘Etienne Devaut & Joseph Delpon’ profile in this book.

X Much information on the Sichuan missionaries is archived at the Archives of the Propaganda in Rome. See Antonio Luigi Landi, et al. “Report of the Four Franciscans of September 29, 1785. Unpublished paper in the Archives of the Propaganda, Vol.38, folders 218-222; and Giov. Battista Marchini, “Catalogo di tutti I Missionari Europei e Cinesi Catturati dal mese di Agosto 1784 Sino a tutto Novembre 1785,” folders 253-256 in the Acrhives of the Propaganda, Rome.

XI Latourette, A History of Christian Missions in China, 173.

XII Giov. Battista Marchini, “Breve Relazione delle persecuzione ultimamentre insorta nell’Imperio della Cina contro la Religione Christiana,” letter dated November 10, 1785, in the Archives of the Propaganda, Rome, fol. 245. English translation cited in Willeke, Imperial Government and Catholic Missions in China, 92.