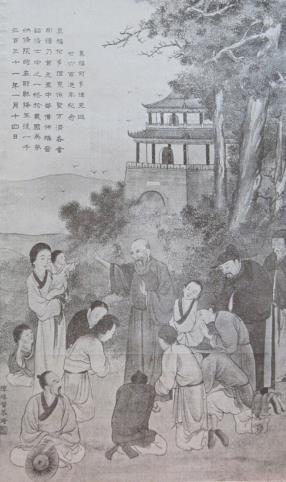

Early Christians in Zhejiang

A Chinese depiction of Odoric of Pordenone, who discovered many Christians in Zhejiang in the 1320s.

The Nestorians, also known as the Church of the East, are generally held to be the first Christians in China. The Nestorian Stone, which was unearthed near the city of Xi'an in Shaanxi Province, describes how the first Nestorian missionary, Alopen, traveled down the Silk Road from Persia (now Iran) or Syria and introduced the gospel to China in 635.

The Nestorians initially found favor with the emperor, who permitted them to teach their doctrine and build churches. They gradually expanded throughout the empire, and Nestorian communities sprang up in a number of trading centers, including several commercial hubs along the east China coast. One of the largest Christian communities was located at Zaitun (now Quanzhou) in Fujian Province, approximately 380 miles (620 km) south of Hangzhou.

The main port for the great city of Hangzhou at the time was located at nearby Ganpu, where the Qiantang River empties into the ocean. Ships regularly sailed from Ganpu to destinations throughout Asia and the world. Merchants and migrants arrived in China via the same port, and thriving communities of Arabs, Jews and Nestorian Christians emerged.

An Arab visitor to Zhejiang during the Tang Dynasty told of a massacre at Ganpu in 878, led by a group of rebels who were part of a secret society. The traveler detailed the mass slaughter of the population of Ganpu, and in the process provided the first documented evidence of Christians in Zhejiang:

"The people of Ganpu, having closed their gates, the rebels besieged them for a long while. The town was at length taken, and the inhabitants put to the sword.... On this occasion there perished 120,000 persons—Muslims, Jews, Christians, and Magi [probably Persians], who had settled in the city for the sake of trade; not to mention the numbers killed who were natives of the country. The number of persons of the four religions mentioned who perished is known, because the Chinese government levied a tax upon them according to their number....

There were at Ganpu a great number of Christians; and they were massacred along with the multitude of foreigners who flocked thither to traffic on the coast of China, and usually to the port of Ganpu."[1]

For the next 400 years all mention of Christians in Zhejiang subsided, and it was not until Marco Polo visited Hangzhou in the early 1280s that evidence emerged of the survival of the Christian faith, with Polo briefly mentioning: "There is one church only, belonging to the Nestorian Christians."[2]

Another four decades elapsed before the Italian Franciscan friar, Odoric of Pordenone (1286-1331), passed through Hangzhou and other parts of Zhejiang. He wrote: "In the land there are many Christians, but more Saracens [Muslims] and idolaters."[3]

Alas, the influence of the Nestorians waned soon after this time. The movement is believed to have become bogged down in sin and compromise, before persecution decimated its churches. The Roman Catholics soon found themselves to be the only adherents of any Christian creed still active in China. Their presence in Zhejiang was minimal, however, and by 1663—more than three centuries after Odoric's visit—only 1,000 Catholics reportedly lived in the entire province, a number which increased to 3,000 by 1703.[4]

Later, early Evangelical missionaries in Zhejiang told a number of interesting stories that suggested a remnant of Nestorianism had survived in the province. In 1852 a missionary in Ningbo, J. Goddard, reported:

"A respectable-looking stranger came into our chapel, and listened with much apparent attention to the sermon. After service he stopped to converse. He said that he and his ancestors had worshipped only one God. He knew of Moses, and Jesus, and Mary; said he was neither a Catholic nor Muslim; neither had he seen our books, but that the doctrine was handed down from his ancestors. He did not know where they had obtained it, nor for how many generations they had followed it."[5]

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book 'Zhejiang: The Jerusalem of China'. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore .

1. L'Abbé Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 1 (London: Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts, 1857), pp. 95-6.

2. Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo, Vol. 2, p. 192.

3. A. C. Moule, Christians in China Before the Year 1550 (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1930), p. 242.

4. Nicolas Standaert, Handbook of Christianity in China 635-1800 (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2001), p. 386.

5. New York Observer (September 2, 1852), p. 283.