Other early Catholics in Tibet

Odoric of Pordenone

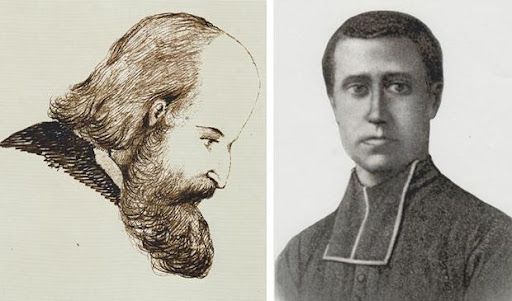

William of Rubruck holds the distinction of being the first European to venture into Greater Tibet in the mid-13th century, followed by Marco Polo 20 years later. There was then a gap of about 50 years until an Italian Franciscan friar, Odoric of Pordenone (1286-1331) reputedly entered Tibet.

After residing in Beijing for three years, Odoric, "listening only to the ardour of his zeal for the propagation of the faith, resolved to go even further, and seek for souls whom he might gain over to Jesus Christ.... Having traversed the vast province of Gansu, he got as far as the capital of Tibet."

Historians disagree as to whether Odoric made it all the way to Lhasa (although some have confidently asserted he arrived there in 1327), or if his writings were based on stories told to him by other travelers. After returning to Italy, he wrote about the capital of Tibet, saying, "It is in this city that the person dwells who is like the Pope of these countries. He is chief and pontiff of all the idolaters, on whom he confers benefices and ecclesiastical dignities according to the rites of the country."

Among his many comments on Tibetan customs, Odoric intriguingly noted that in Tibet "a number of Catholic missionaries were effecting numerous conversions."

After having been away from home for 16 years, Odoric is said to have returned to Europe after crossing the Himalayas and traveling via India and Persia, arriving in Italy in 1330. Although he was only 43, the exertions of his travels had taken a toll on Odoric's body and he died the following year. It was said that "When he again beheld his native country, he was so changed by the sufferings and miseries he had endured, his body was so emaciated, and his face so withered and blackened by the sun that his relations could not recognize him."

Later Europeans perpetuated a romantic narrative of Odoric's life and ministry, with one author claiming the friar had baptized 20,000 heathens during his missionary travels, while claims were made of flourishing Christian communities "even among the nomadic tribes of Tibet, who were converted by Odoric."

The same source, however, lamented that when "at the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth centuries, new apostles appeared in those countries, they found none of the Christians of the Middle Ages. Those missions, which once promised so abundant a harvest, had been devastated by storms, or dried up for want of nourishment, and the field was overgrown by thorns and brambles."

Catholic Rituals Absorbed by the Tibetans

Although no known Christian community endured in Tibet after the demise of the Guge mission in the 17th century, fragments of many Catholic rituals appear to have been adopted by the Tibetans. In the Bon religion and among the Nyingpa school of Tibetan Buddhism, a ritual known as tshe-bang or 'life consecration' was practiced. One scholar remarked: "The central element of this rite is the distribution by the officiating priest among the attending congregation of wafers of consecrated bread and wine sipped from a chalice."

Later visitors to Tibet commented on the similar rituals shared by Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism. In 1870 one magazine article surmised:

"No one who ever visited Buddhist countries will be surprised at the suggestion that modern Buddhism looks extremely like a gross caricature of the Roman Catholic Church; seeing that the Buddhists everywhere have their monasteries and nunneries, their baptism, celibacy and tonsure, their rosaries, chaplets, relics and charms, their fast days and processions, their confessional, mass, requiem and litany, and—especially in Tibet—even their cardinals and their pope."

There seems little doubt that the Tibetans absorbed many religious rituals from early Catholic visitors like Odoric, but tragically, it appears those representatives of Christ did not proclaim the gospel to the Tibetan people in a way that resulted in them repenting of their sins and placing their trust in Jesus Christ alone for salvation.

Ippolito Desideri

After the demise of the Jesuit mission in the kingdom of Guge, nearly a century elapsed before Catholics again entered Tibet. Italian missionary Ippolito Desideri and his companion Manuel Freyre succeeded in reaching Lhasa in March 1716. Freyre soon returned to India, but Desideri remained in the Tibetan capital for five years, meeting with the Mongol king of Tibet, who granted him permission to preach and also to buy a house.

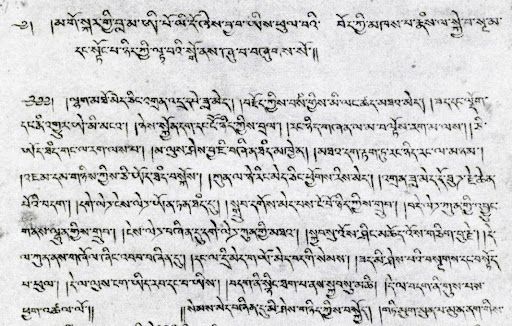

Desideri devoted himself to daily study of the Tibetan language, which he did from morning till night. He progressed so rapidly that on January 6, 1717, he was able to present a discourse on the Christian religion to the king and his officials. His plan was to write a Tibetan-language refutation of the errors of Buddhism and a defense of Christianity, but his progress was suddenly halted when the Qing armies marched from China and sacked Lhasa in December 1717, putting the king and his ministers to death. Desideri fled the capital and took refuge at Takpo Khier, eight days distant.

For the next four years the Italian worked on his book, making great progress. Finally, he returned to Lhasa and presented his three volume work to the leading Buddhist lamas.

Having been completely cut off from the outside world for years, Desideri was shocked to learn that the Vatican had taken Tibet from the control of the Jesuits, reassinging the region to the Capuchin Fathers, a move described by one scholar as "a disastrous bungling administrative decision by the Catholic Church." With his funding now cut off, he was forced to abandon his ministry just as it was beginning to make inroads. Desideri left Tibet for Nepal in 1721.

Desideri's brilliant academic mind and focus on studying the Tibetan language places him above almost all other Christian missionaries to Tibet throughout history. His works are still considered classics by both Tibetan and Western scholars. A contemporary author has remarked:

"In the upper left-hand corner of the first page of his Inquiry, he wrote the date June 24, 1718. He had first encountered the Tibetan language...just three years before. This would be akin to a Tibetan monk making his way from Lhasa to Rome without knowing Italian or Latin, and three years after his arrival writing a 400-page refutation of Aquinas's Summa Theologica, in Latin. It borders on the miraculous."

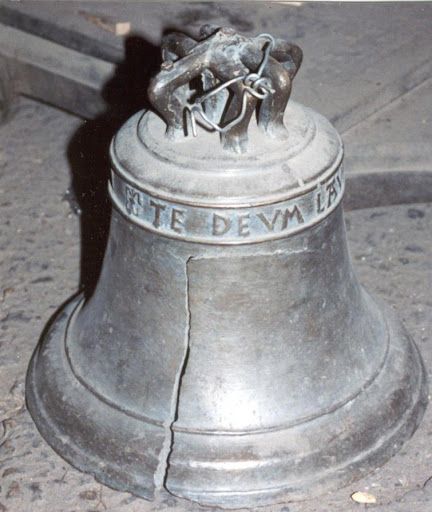

The Mysterious Church Bell

After several decades of struggle, the Capuchins were expelled in 1760, and no more Catholic missionaries entered central Tibet for nearly 200 years, with the notable exception of the French Lazarists Evariste Regis Huc and Joseph Gabet, who went against the directive of their superiors by disguising themselves as Buddhist monks and traveling across the vast Tibetan Plateau.

The duo reached Lhasa in 1844, where they distributed gospel tracts and entered into debates with Buddhist leaders. They won the favor of the Tibetan regent, who allowed them to set up a small chapel in their home for worship and to explain to visitors the meaning of their large pictures of Christ's crucifixion. The regent said:

"Your religion is not the same as ours. It is important we should ascertain which the true one is. Let us, then, examine both carefully and sincerely. If yours is right, we will adopt it. How could we refuse to do so? If, on the contrary, ours is the true religion, I believe you will have the good sense to follow it."

The Chinese ambassador in Lhasa was strongly antagonistic toward Huc and Gabet, however, and he had them deported from Tibet in 1846. They returned to France, where they were expelled from the priesthood for disobeying orders, and their careers ended in ignominy.

Despite a fascinating history of endeavor and promising breakthroughs, most notably with the Jesuit mission to Guge in the early 17th century, more than 500 years of sporadic Catholic work had failed to produce a single enduring church in central Tibet.

Krick and Bourry

After reaching India in 1848 at the age of 29, Frenchman Nicolas Krick searched for a way to cross the Himalayas and enter forbidden Tibet. He journeyed north through areas inhabited by the Adi, Mishmi and Lhoba tribes, before crossing into Tibetan territory in January 1852. Krick immediately encountered fierce opposition from hostile locals. He could find nowhere to sleep, and the people refused to sell him any food. In order to survive, Krick "was forced to collect grains of rice that had fallen on the ground and to scavenge for the disgusting leftovers from other people's meals, which even dogs refused to touch." After a few days he was driven back across the border into India.

After recovering from his ordeal, the audacious Frenchman made plans to re-enter Tibet. He set out in 1854, this time accompanied by a young compatriot, Augustin Bourry. The duo had their sights set on reaching Lhasa, but three months later Krick wrote in his diary:

"For 90 days I have been marching barefoot. All my shoes are ruined.... For two weeks we walked in non-stop rain, which poured down as from a cloudburst and completely ruined all our books. To complete this picture of misery—in the mountains you may fall prey to manifold sicknesses like fever, dysentery, rheumatism and sores from insect bites."

Worn out from their exertions, Krick and Bourry rested at a village for a few months, where they studied Tibetan and dispensed medicine to the sick. Then on September 1, 1854, Chief Kaisha of the Mishmi tribe attacked Krick and Bourry with a mob armed with spears and machetes. One account records: "Kaisha caught up with them and cut them to pieces. The grieving villagers buried them with honor under a cairn of stones."

It was later discovered that the slaying of the missionaries had been ordered by the Tibetan authorities, who were eager to prevent Christianity from gaining a foothold in their territory.

Krick and Bourry's courageous attempt to enter Lhasa was over, having fallen short of their goal. They were buried in a remote area in what is today the state of Arunachal Pradesh in northeast India. Their sacrifice for Christ is still remembered, however, and the Krick and Bourry Memorial Hospital was opened in the town of Injan in 2016. The area today contains many Christians, including believers from the Mishmi tribe that had killed the two missionaries more than 150 years earlier.

Although Catholic work in central Tibet had stalled, progress was more encouraging in the outlying regions. A steady stream of French missionaries with the Paris Foreign Mission Society came to the Tibetan borders, especially in areas within today's Yunnan and Sichuan provinces. In some of the most remote stations on earth they labored valiantly among the Tibetans, often enjoying marked success. By 1870, Tibetan areas in what is now China "were said to have about 900 Catholics and in 1890 a little over 1,100."

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book ‘Tibet: The Roof of the World’. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 1, p. 369.

2. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 1, p. 370..

3. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 1, p. 371. Also see Odoric of Pordenone, The Travels of Friar Odoric (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2001).

4. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 1, p. 371.

5. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2, p. 16..

6. Huc, Christianity in China, Tartary, and Thibet, Vol. 2, p. 249.

7. Charles Allen, The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History (London: Little, Brown Book Group, 1999), p. 170.

8. E. J. Eitel, "Buddhism verses Romanism," The Chinese Recorder (November 1870), p. 142.

9. Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China, p. 40.

10. S. Donald Lopez Jr. and Thupten Jinpa, Dispelling the Darkness: A Jesuit's Quest for the Soul of Tibet (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), p. 29.

11. Tsering, Sharing Christ in the Tibetan Buddhist World, p. 49.

12. Cited in Ralph Covell, "Buddhism and the Gospel among the Peoples of China," International Journal of Frontier Missions (July 1993), p. 133.

13. My translation of the Biographical Note of Nicolas Krick in the Archives des Missions Etrangères de Paris, China Biographies and Obituaries, 1800-1899.

14. Thomas Menamparampil, "In the Footsteps of Murdered Mission Heroes: Mountain Quest for Lonely Spot Where Martyrs Died," Mission Today (Spring 2003).

15. Menamparampil, "In the Footsteps of Murdered Mission Heroes," Mission Today (Spring 2003).

16. An account that pieces together the story of Krick and Bourry's ill-fated journey is François Fauconnet-Buzelin, Mission Unto Martyrdom: The Amazing Story of Nicolas Krick and Augustine Bourry, the First Martyrs of Arunachal Pradesh (India: Don Bosco Centre for Indigenous Cultures, 2001).

17. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christian Missions in China (New York: Macmillian & Co., 1929), p. 328.