1950s

Geoffrey Bull.

George Patterson had traveled to China with a Brethren missionary named Geoffrey Bull. The duo intended to spread the gospel among Tibetans, but whereas Patterson went on to become a famous and divisive figure in the mission world, Bull was arrested in the Kham region and spent three years in prison for his faith, before the Communists declared that he had confessed his "crimes against the people" and expelled him from the country. Bull recalled the emotions he felt as his train made its way toward the Hong Kong border and freedom:

"Year after year, I had lived for this day. God knows all that it had meant. With blow after blow, I had been spiritually and psychologically bludgeoned, until I was dazed and broken in mind and spirit, but none had been able to pluck me from my Shepherd and His Father's hand.

In the crisis, I had found my faith and love at times too weak to hold Him fast, but the final triumph was not to be in my hold of Him, but in His hold of me. His love would never let me go. He would keep that which I had committed to Him. In His own time and way, He was determined and able to make me all the man that He had planned that I should be. I was broken, but I had proved His Word unbreakable."

Upon returning to Britain, Bull gradually recovered from his ordeal and told his story in a best-selling book, When Iron Gates Yield. He married in 1955, and subsequently served as a missionary in Borneo (now part of Malaysia). Geoffrey Bull continued to be a leading Brethren teacher for decades until his death in 1999, at the age of 78.

Kham ཁམས་

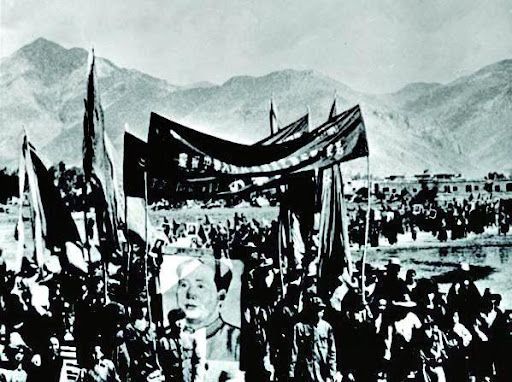

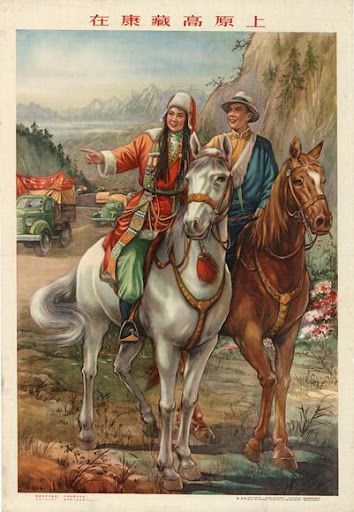

The 1950s saw Khampa society decimated by Mao's forces as they invaded the region, leaving a trail of destruction in their path. Life in Kham was never to be the same again.

In 1950 the Chinese captured the town of Qamdo without firing a shot. The Khampa fled in terror when the People's Liberation Army set off a huge fireworks display on the outskirts of the town. The Tibetans had never seen fireworks before and presumed they were being bombarded with a new weapon.

In late 1955 the Communist authorities ordered the lamas of the large Litang Monastery to make an inventory of the monastery's possessions for tax assessment. When the lamas refused to oblige, soldiers laid siege to the monastery, which was defended by several thousand monks and farmers, many of whom were armed with farm implements.

Chinese aircraft were called in to bomb Litang, destroying the monastery and killing hundreds of people. The Tibetans, outraged by the attack, spread the conflict to the surrounding towns of Dege, Batang, and Qamdo. They fought for their very existence, not caring whether they lived or died, but their efforts were no match for the Chinese tanks and well-drilled army.

Rocked by the savagery of the attacks on his people, the Dalai Lama set up a Commission, which documented some of the atrocities that had been committed by the Chinese against the Tibetan people:

"Tens of thousands of our people have been killed, not only in military actions, but individually and deliberately. They have been killed, without trial, on suspicion of opposing Communism, or of hoarding money, or simply because of their position, or for no reason at all. But mainly and fundamentally they have been killed because they would not renounce their religion.

They have not only been shot, but beaten to death, crucified, burned alive, drowned, vivisected, starved, strangled, hanged, scalded, buried alive, disemboweled, and beheaded. These killings have been done in public. The victims' fellow villagers and friends and neighbors have been made to watch them, and eyewitnesses described them to the Commission.

Men and women have been slowly killed while their own families were forced to watch, and small children have even been forced to shoot their parents.

Lamas have been specially persecuted. The Chinese said they were unproductive and lived on the money of the people. The Chinese tried to humiliate them, especially the elderly and most respected, before they tortured them, by harnessing them to plows, riding them like horses, whipping and beating them, and other methods too evil to mention. And while they were slowly putting them to death, they taunted them with their religion, calling on them to perform miracles to save themselves from pain and death."

The Chinese had a markedly different view of the conflicts, however, with one account declaring:

"The imperialists and a small number of reactionary elements in Tibet's upper ruling clique could not reconcile themselves to the peaceful liberation of Tibet and its return to the embrace of the Motherland.... Contrary to their desires, this rebellion accelerated the destruction of Tibet's reactionary forces and brought Tibet onto the bright, democratic, socialist road sooner than expected."

In 1950, just prior to the curtain being permanently drawn on foreign Christian work, missionary Edward Beatty provided a final glimpse into the state of Christianity throughout the Kham region:

"In the town of Kangding there are four full-blooded Tibetans who are Christians; one a gifted artist who was formerly engaged in the lucrative work of idol painting. There are also four or five Christian women of Chinese-Tibetan parentage, more Tibetan than Chinese. Finally, there were three other Tibetans called of the Lord, for a time, to the preaching of the gospel, who are now in His presence in glory.

Workers of another mission living in the small town of Garze were privileged to see four or five Tibetans baptized on confession of their faith in the Lord Jesus. Also in several villages of Chinese Tibet there are other Christian Tibetans."

Due to the godly influence of missionaries like Albert Shelton, the remote town of Batang had become a hub of Christian activity in the Kham region prior to the chaos of the 1950s. Years later, a Tibetan Christian using the pseudonym Andrew detailed the impact the gospel had made there:

"I was born into a Christian Tibetan family. By God's favor I was led into His presence in my early childhood and became part of the Christian flock. Through the teaching of church members I grew up to become a servant of Jesus Christ. God blesses and preserves me all the time. Thank you Lord! I will glorify and serve Him all my life....

Many Tibetans became believers in those days. People repented after hearing the Word of God, and began living by the truths of the gospel. They accepted the Lord's redemption, proclaiming Jesus as the only God, who came to earth in bodily form as a human being. Tibetans followed and served the Lord with faithful hearts. Many of them were baptized as well. When Christianity was prevalent in Batang, there were more than 100 believers. God blessed us abundantly."

The long Catholic missionary era in Tibetan areas also came to an end in the early 1950s. The Kham region, with thousands of converts, had seen the strongest results for Catholic work among Tibetans, with even a rival Evangelical scholar admiring their commitment and strategic approach:

"Catholic missionaries lived simple lives among nomads and learned well the life and culture of the people. They were prepared to dialogue philosophically with the lamas or to deal directly with village people on their fears of the spirit world. Seeking wherever possible to promote people movements, they were able to establish Christian communities to which they then ministered through hospitals, schools, seminaries, and institutions of compassion. Their work on both sides of the China-Tibet border has proved to have more lasting quality than any of the many ministries engaged in by Protestant missionaries in the same areas."

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book ‘Tibet: The Roof of the World’. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

1. Geoffrey T. Bull, When Iron Gates Yield (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1955), pp. 250-51.

2. See Michael Peissel, Cavaliers of Kham: The Secret War in Tibet (London: Heinemann, 1972).

3. The Dalai Lama: My Land and My People: Memoirs of the Dalai Lama of Tibet (New York: Potala Corporation, 1962), pp. 221-22.

4. Beijing Review (June 27, 1983).

5. E. E. Beatty, "Tibet: a Notable Observation," China's Millions (December 1950), p. 125.

7. Andrew, "The Lord's Grace: The Establishment of Batang Church," self-published report, no date.

8. Covell, "Buddhism and the Gospel among the Peoples of China," International Journal of Frontier Missions (July 1993), p. 134.